By: Tessa Stuart

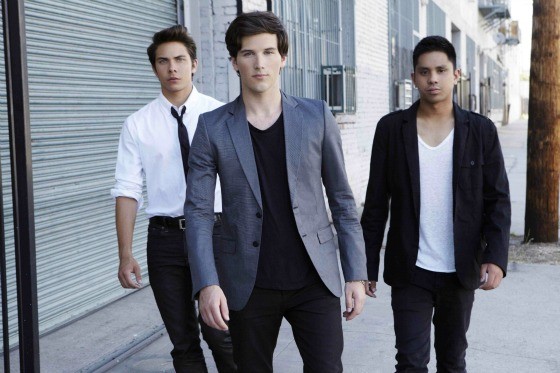

Boy band Allstar Weekend are Poway's answer to One Direction. The San

Diego county-bred group got its start on the Disney Channel music

competition Next Big Thing back in 2009. They took second place

on that show, but the exposure helped the band ink a four-album deal

with Hollywood Records, book a tour with Selena Gomez and score a few

spreads in J-14 magazine.

Two albums into their record contract, though, Allstar Weekend and

the label ran into “creative differences.” The latter wanted to continue

milking the younger demographic, the former wanted to make more mature

music, and they parted ways.

To fund their next work, this summer Allstar Weekend turned to

Kickstarter. The trio, now living in Burbank, made a video asking fans

for help and compiled a list of rewards for donating.

A $15 pledge was good for an early digital release of the new album.

For $5,000, one received a slew of autographed merchandise and a full

day hanging out with the band at Disneyland or Universal Studios.

The campaign was a huge success, raising some $96,000 — more than

three times its $30,000 goal — including three fans who ponied up

$5,000 apiece.

“It's cool,” 23-year-old lead singer Zach Porter says of one top

donor who recently cashed in her reward. “She was just a really big fan,

and we got to hang out with her all day.”

It's hard to imagine something like this happening even as recently

as a few years ago. But nowadays this type of crowd funding, along with licensing, can feel like the only things keeping the record industry afloat.

Because of illegal downloading, it has grown increasingly tough to

make a profit selling music; industry experts once suggested that

full-time musicians could make up their losses via touring performances

in front of … all the fans who stole their music.

But so far that doesn't seem to be doing the trick, so platforms like

Kickstarter, Indiegogo and PledgeMusic — which is sort of like

Kickstarter but exclusively for musicians — have stepped in.

Artists now can ask fans directly: How much is our music worth to

you? To many, the answer is, “a lot.” Since the platform launched in

2009, Kickstarter has helped fund more than 30,000 creative projects —

records, films, graphic novels, inventions — raising a whopping $400

million.

Although it has the reputation for being the domain of unknowns,

Kickstarter increasingly is becoming the first choice of the famous,

too: Amanda Palmer raised more than $1 million there this year.

PledgeMusic funded Kate Nash's new record. Ben Lee, Here We Go Magic and

10,000 Maniacs all have campaigns in progress on the site.

But crowd funding might not be a panacea for the industry, and in

fact it's not nearly as easy or cost-effective as it sounds. Unseen

costs, fees and taxes can take a big bite out of a band's big payday.

For starters, the IRS wants in on the action.

[

In 2011, the agency introduced the 1099-K form. While it doesn't target

crowd funding specifically (no, the K doesn't stand for Kickstarter) —

it is meant to keep track of third-party credit-card transactions, such

as the pledges that Amazon processes on behalf of Kickstarter. Thus,

anyone who raises more than $20,000 or logs at least 200 transactions on

Kickstarter is required by the IRS to file the form. Don't think you

can weasel out, either, because Amazon reports the information to the

government.

The fact that the IRS is quietly accounting for the money raised on

Kickstarter is catching some artists off guard — like Zach Porter of

Allstar Weekend, for example. “That is definitely something that I have

to look into,” Porter says.

In January, local singer-songwriter Ari Herstand raised $13,500 from

222 backers for recording costs — which means this year he'll have to

file a 1099-K. When pressed, he admits that he has no idea what his tax

responsibility will be, and Kickstarter provides little information

about the subject on its site.

A Kickstarter representative declined to be interviewed for this story, and no one from the IRS would speak with the Weekly, either — pointing us only in the direction of published material, of which there isn't any yet about crowd funding.

But accountants told the Weekly it's really not clear how musicians should classify this type of money on their tax returns.

In fact, it turns out that Herstand might not even have to pay taxes on his pledges at all.

It all hangs on a philosophical-sounding question: What is a pledge? Is

it a sale? That might depend on the reward — a CD in exchange for a $15

pledge, for instance, might be considered a sale.

Alyce Bonura, of Sherman Oaks-based tax consultants Bonura &

Associates, who has worked as an entertainment-industry accountant for

30 years, doesn't believe that to be the case. If a band is raising

money to make an album, Bonura says, profit from that work is what

counts as income, and that's what the band will be taxed on “after they

deduct their expenses: the album-cover designers, the recording studios.

All that stuff.” The rewards, she argues, could be written off as

promotional costs.

“It is not income,” Bonura says. “It is either an investment, a gift

or a loan,” though it's only a loan if there is a contract outlining the

terms of such an agreement. If it's a gift, you're not required to pay

taxes on it up to $13,000 in value.

[

Gregg Wind, a CPA at West L.A.-based Wind & Stern, agrees that it's

debatable whether the money qualifies as a gift or income. “I don't know

if it's clear yet. I would say that it's an evolving area.”

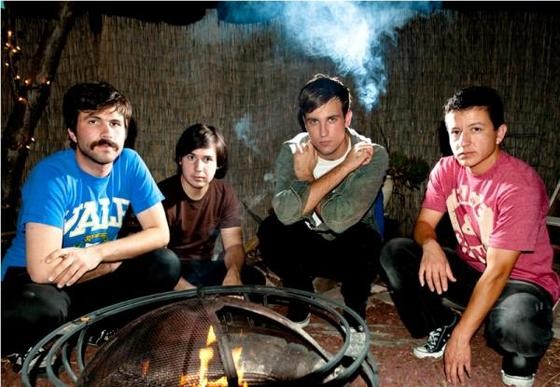

Echo Park-based band LA Font closed a round of Kickstarter funding

last year. One hundred and sixty supporters backed the project, from

friends and fans to music bloggers.

“It gave everyone the chance to say: I'm into this, I've got skin in

the game, I want this to succeed,” member Greg Katz says. “That said,

would we do this again? The answer is probably no.”

They set their goal at $9,000, and pulled in $9,135, but their cut

was smaller. Kickstarter and Amazon each immediately took their 5

percent, leaving the band with $8,222. After that, they had to fulfill

various rewards promised to backers, including posters, vinyl records

and the chance to dictate Katz's facial hair for a week (Exception: no

Hitler mustache). Then there was the shipping materials and the postage.

With the money LA Font had left, they hired a name producer, Eric

Palmquist, and booked some time in an East L.A. studio. A year after the

campaign, they've recorded an album they are proud of. But having used

up the money on studio time, they'll have to fund the few thousand

dollars more it will cost to mix, master and press the album onto vinyl

themselves.

That's OK, though, Katz says. After all, their Kickstarter campaign

was only meant to help them on their way to making a great record — one

that might ultimately land them a deal with a label.

Follow us on Twitter @OCWeeklyMusic and Like us on Facebook Heard Mentality.