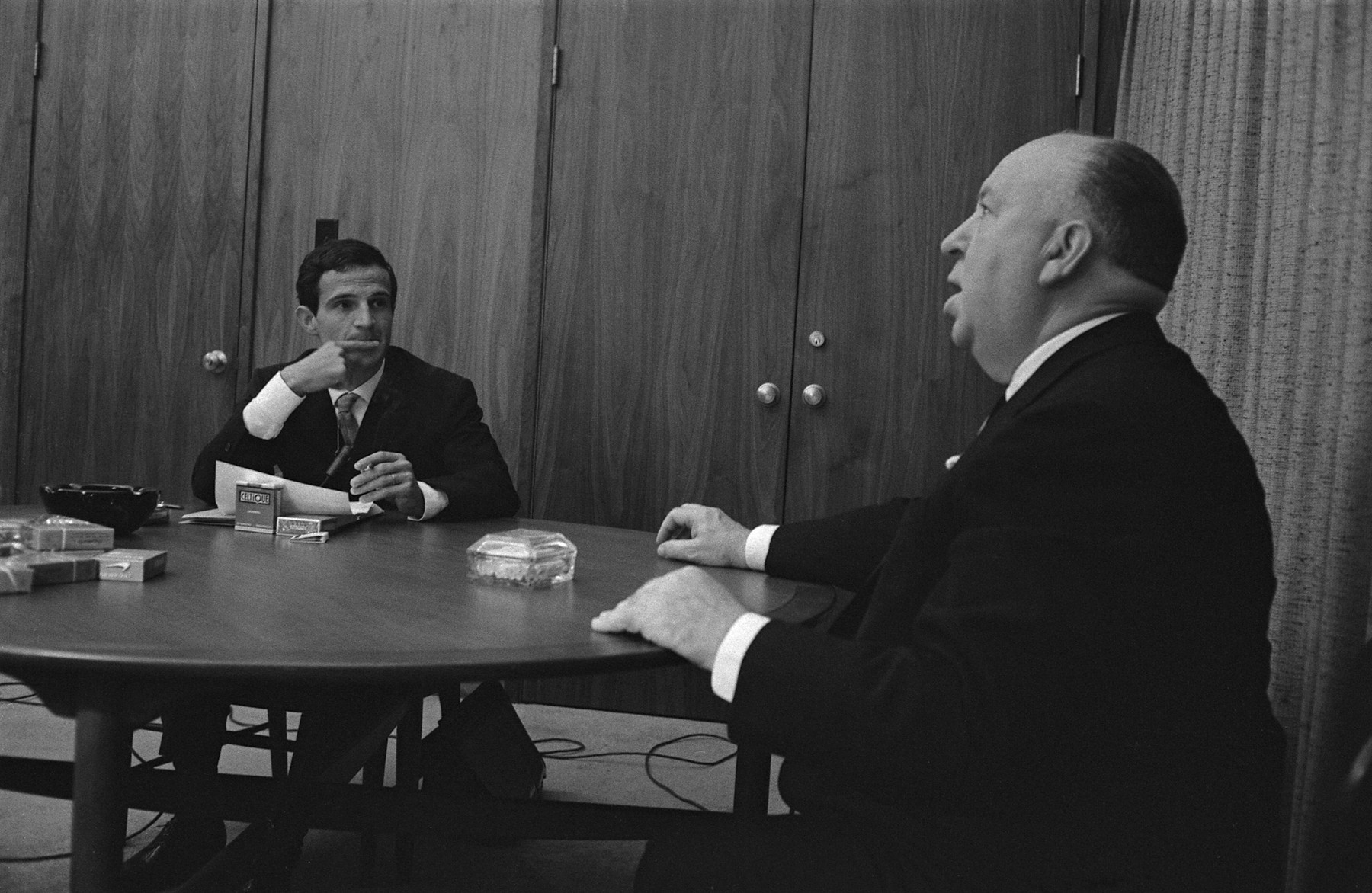

They could have called it Hitchcock/Truffaut/Scorsese/Fincher. Less an adaptation of one of the great books about film than a feature-length recommendation, Kent Jones's documentary take on François Truffaut's exhaustive career-survey 1966 interview with Alfred Hitchcock is an arresting précis, sharply edited and generous with its film clips—it's a smashing supplement to Truffaut's classic study.

It's a thrill to hear the directors' voices, recorded fifty years ago. Hitchcock, in that clipped and finicky rumble of his, describes the precise moment in Vertigo when Jimmy Stewart's character is worked up at last to a full erection. Jones and editor Rachel Reichman layer the talk over the scene itself: Stewart's frayed-nerve detective Scottie, almost panting in a hotel room lit the green of lime Jell-O, while Kim Novak's Judy at last ducks out to put her hair up in the manner of the dead woman he loves. To his credit, Hitchcock's matter-of-fact commentary makes a deliciously sick moment even more so.

But don't expect many such thorough explications. Jones's film, which comets through Hitch highlights before getting caught up in the gravity of Psycho and Vertigo, is no substitute for the book itself, which examines each of Hitchcock's movies, at some length, from the rarest of perspectives: that of working artists. In that epochal conversation, Truffaut and Hitchcock engaged in an elevated sort of shoptalk focused on the techniques the latter chose to achieve his artistic ends, whether narrative, visual, or psychological. Yes, the print volume gives you the moment Scottie got hard, but more pressing are the director's nuts-and-bolts thoughts on pacing, on framing, on symmetry within a story and within a shot, on the creation of what Hitchcock, who started in silents, considered “pure cinema”: telling the story through the images.

To that end, Truffaut published fascinating shot-by-shot and beat-by-beat examinations of key sequences: Stewart (in the second The Man Who Knew Too Much) confounded that his fingers are streaked with paint from the face of a man murdered in a Marrakesh marketplace; Martin Balsam ascending—and then flailing back down—the staircase in Psycho. Jones, too, shows us these scenes, but it's different to see them onscreen once again than it is to regard them on the page, to puzzle out the logic of pacing and cutting in your own mind. Truffaut also reproduces Harold Michelson's storyboards laying out the accumulation of ravens on that playground in The Birds, but the film of Hitchcock/Truffaut notes few of the talented souls who worked on these films, presenting Hitchcock as a singular visionary more often than as a technician, craftsman, or collaborator.

Jones has assembled today's directors of note to chip in. They tilt his film from shoptalk to awed appreciation, and too many rhapsodize about Hitchcockian generalities rather than his specific intentions and choices in individual films. (Jones, a film historian and programmer, mines the oeuvre to illustrate the vague encomiums.) Some, though, justify the decision to bring in more voices. David Fincher is amusing on the perversity of both Vertigo and its director's handling of the actors, whom, speaking to Truffaut, Hitchcock once characterized as cattle. “He probably did more for the psychological underpinnings of characterization in motion pictures than anyone,” Fincher says. “And on top of it wouldn't allow any of his actors to explore any of that behavior on set.” (Jones's doc breezes past Hitchcock's cattle comment and other Film 101 hits from the book—the term “macguffin” or the bomb-under-a-chair formulation of the difference between suspense and surprise.)

James Gray illuminates the museum scene in Vertigo, and Martin Scorsese is—as ever—alive to detail. He occasionally takes over Hitchcock/Truffaut, but since the film only rarely slows down and lets us hear artists pick apart approaches and technique, Scorsese's sustained arias win the day: He marvels at the framing of Janet Leigh behind the wheel of a car in Psycho, describing the other ways Hitchcock might have composed the shots—and why the one we know is so effective. Scorsese's great on the intentional flatness of much of Psycho's first forty minutes, on the necessity of the meditative driving scenes, on the way the technique becomes inventive and elaborate only when it must, to jar us. Being Scorsese, he finds something “religious” in the high-angle shot of “Mother” stabbing Balsam's detective, just as he does the God's-eye vision of Bodega Bay in flames in The Birds and the peering-down-at-a-lying-spy perspective in åTopaz.

Scorsese speaks of film as incantatory but filmmaking as a series of practical decisions. That exemplifies the spirit of the book even as it's at odds with that long-ago interview's un-elevated tone. It fits, though. Truffaut's book revealed for critical audiences what should have been apparent all along: that Hitchcock, though working in studio Hollywood, was as much an artist and master as any of the greats of world cinema. It's hard for us to imagine today how such an intervention might have been necessary. Speaking with something like divine fervor, Scorsese puts the best possible face on today's passionate, almost universal lionization of 'ol Hitch: He's ecstatic, but he's focused on the craft of mastery rather than the simple fact of it. At its best, this Hitchcock/Truffaut is, too.

Hitchcock/Truffaut was directed by Kent Jones.