Courtesy of Historic Wintersburg/The Furuta Family Collection

There are currently five branches of Public Storage’s self-storage facilities in Huntington Beach, with talks of adding a sixth. Coincidentally, there are just five buildings that remain from the earliest days of the Japanese settlement in Orange County during the infancy of the 20th century in what is now Huntington Beach.

On the corner of present-day Warner Avenue and Nichols Lane stands 5 acres of land haphazardly hidden behind tarps and wire fences. Passersby may know the area best for the large, colorful mural proclaiming, “Jesus Lives” on the side of a dilapidated, boarded-up building. But Jesus don’t live here no more.

The corner stands out among the beige apartment buildings and strip malls that have sprung up around it as the city of Huntington Beach transitioned from farmland to the “Surf City” of today. And the vacant, overgrown, largely forgotten square of land called Historic Wintersburg is in danger of being swallowed up by the sea of corporate progress and commerce it has staved off for decades.

But there was a time, back when the name Pacific City referred to the nice, quiet, little beach community it once was, before Duke Kahanamoku or George Freeth ever surfed the waters just off the city’s shores, when this pocket of land was the vibrant cultural hub of early Japanese settlement in OC.

This story, as with a good many of foundational Orange County, begins with agriculture. In 1893, the small community of mostly celery and beet farmers in what is now northern Huntington Beach named this small patch of the then-brand-new Orange County Wintersburg after a local farmer, Henry Winters.

Pioneers of the area had young Japanese and Chinese men tending their fields in the late 1800s and into the early 1900s. One such Japanese laborer was Charles Mitsuji Furuta, who arrived here around age 22 by way of Tacoma, Washington, around 1904. He grew up within a family of farmers in Hiroshima-Ken, not too far from the capital city of Hiroshima, so seeking work as a farmhand in America was a natural transition. An enterprising young man, Furuta entered into a partnership with four other Japanese immigrants to run their own farm within a few years of arriving in Wintersburg. When the farm flopped, the others fled, leaving Furuta with $10,000 in debt (that would be $259,000 today), but he was determined to pay off his debts and make it as a farmer in America.

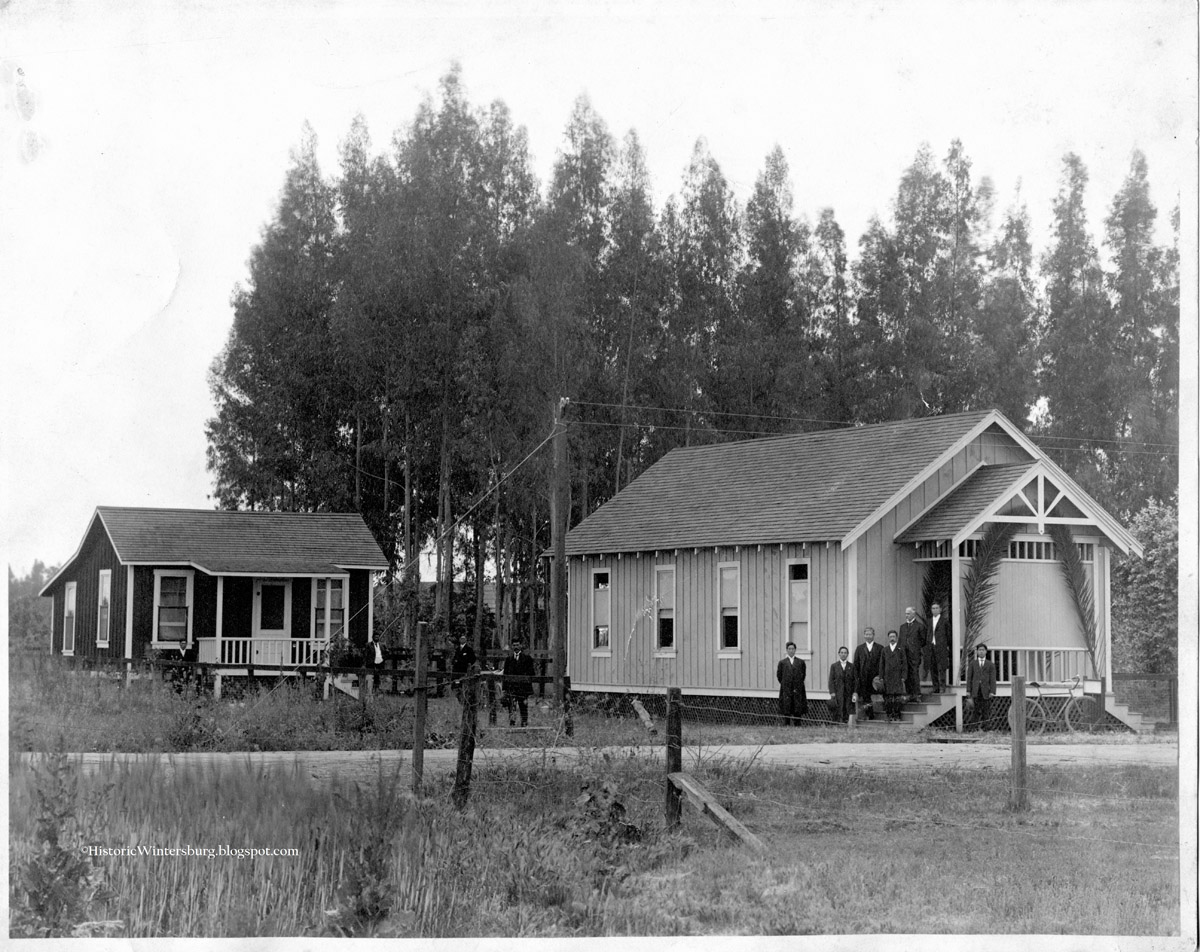

As the population of Wintersburg grew, so did the residents’ need for a church. The Cambridge-educated Reverend Barnabus Terasawa founded the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1904. The outreach, literally born in a barn, was open to a variety of faiths (Terasawa himself was Episcopalian).

By 1908, the reverend had bought 5 acres of land—the same plot in danger today—with financial assistance from Furuta. The following year saw construction on the church, and then the steeple, and by 1910, you could open the door and see all the people. “A lot of prominent people ended up being associated with this little mission,” explains Mary Urashima, chairwoman of the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force. “It was a mission of interfaith and a meeting place for people learning to become American.”

At 31, Furuta briefly traveled to Japan to meet his new bride via an arranged marriage. He brought 17-year-old Yukiko Yajima to Huntington Beach in December 1912 to settle into their marital home, dubbed the Bungalow. Yukiko was not like the other farmers’ wives: By several accounts, she was quite fashionable, and her husband would not let her work in the fields. Instead, she spent her days behind locked doors, writing letters to and longingly reading letters from home.

In 1912, Terasawa and his wife decided to move to San Francisco (which just goes to show the idea of ditching the 714 for the 415 isn’t at all a new phenomenon), and the land was deeded to Furuta. But then California saw fit to enact the Alien Land Law of 1913, which effectively banned non-American citizens from owning land. (Japanese immigrants were prohibited from becoming U.S. citizens at the time.) All land purchased by non-citizens prior to 1909 remained in the hands of the owners, so Furuta’s farm narrowly stayed with him. The Historic Wintersburg property that remains today is the last vestige of pre-Alien Land Law Japanese-owned land in the county.

Of course, where there’s racism, there’s often resistance. “The Japanese were very hard workers,” early city historian Delbert “Bud” Higgens recalled in a 1968 interview for Cal State Fullerton’s (CSUF) oral-history project. “They accumulated money, and then bought land in the name of their children, who were born here. So a lot of the farmland around the area here was owned by Japanese children.”

Despite the overt racism against those of Asian descent seen in California and federal laws, Japanese immigrants and their children, the nissei, made a life for themselves in Huntington Beach and were active members in the community at large, with charitable outreach in present-day Laguna Beach, Fountain Valley and Costa Mesa. “The Japanese were very close people that stuck together,” Higgens recalled of the time. “Of course, we got along with them. The boys and girls were very studious, good students and good athletes. Many of the Japanese boys were good football players and good at all sports.”

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service perpetrated a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base of Pearl Harbor near Honolulu, Hawaii. It happened around lunchtime here in California, and by just after dinnertime, FBI agents were already detaining Orange County’s Japanese residents.

Though the attack on Pearl Harbor specifically came as a surprise to most, skepticism of Japanese-Americans had already been brewing. “When it looked as if we might become involved with Japan during World War II, everybody was worried about Japan and what they were going to do,” recalled J. Sherman Denny in a 1968 interview published by the CSUF oral-history project. “Some of the American Legion men felt that a lot of these pepper-dryer plants [Japanese pepper farmers were prominent in the area] here were places that guns were stored and that we’d really be in trouble if war broke out and the rumors happened to be true.”

Local residents grew concerned over a local Japanese businessman who took a lot of photos, fearing he was sending those images to the Japanese government. The chicken wire used to protect the goldfish ponds on the Furutas’ farm was seen as potential radio transmitters used to convey secret messages.

These theories illustrate the growing xenophobia and paranoia around the country leading up to and after the U.S. joined World War II. Just more than two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which began the systematic removal of Japanese-Americans along the West Coast. Within two days of the new executive order, the FBI interrogated Furuta.

Furuta had been living in America for 41 years by the time he was incarcerated and sent to a Department of Justice prison camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico, in 1942. His wife and six children were removed from their home—which still stands on the Historic Wintersburg lot—in May of that year and sent to a camp in the blazing heat of Poston, Arizona. After numerous letters of appeal, the family was reunited in Poston in 1943. The Furuta family then remained together for the rest of their internment.

Just after V-J Day in September 1945, Japanese-Americans were released from American camps. Yukiko Furuta was so eager to return to her farm that she hopped onto the back of a milk truck to begin her journey back to Huntington Beach. “When I returned, the ground was so full of weeds I couldn’t tell where the fish ponds were,” Yukiko recalled in a 1982 interview. Charles joined her a couple of weeks later.

Many Japanese-Americans made new lives elsewhere after being released from the internment camps. Some had their land seized and sold by the government or their homes destroyed. The Furutas’ home and farm, as well as the church on their property, survived against the odds. The family rebuilt, transitioning from goldfish farmers to sweet pea and lily growers, and remained there until the 1990s.

The current owners, Republic Services, who handle Huntington Beach’s waste management, had been in talks with the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force to sell the land, which had slowly entered a state of decay over the years because of non-use. “[The Task Force and the National Trust for Historic Preservation] had been working with them in good faith,” says Urashima. “We had been offering to purchase the property at face value from them.” She adds that after years of working with the owners and the city of Huntington Beach, Republic stopped returning any attempts at communication.

On Jan. 26, news broke that Republic Services planned to sell the historic site to Public Storage. Though it was named a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, it is set to be bulldozed to make way for people’s excess shit.

Urashima points out that by selling the historic property to preservationists to restore the site and turn it into an educational museum, they would be repurposing and reusing existing resources—something Republic touts as its message. “If they change their mind, we still offer this,” she says.

“We’re dismayed that there was no discussion,” Urashima adds. “We’re baffled by their choice to effectively destroy a national treasure—forever. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

When not running the OCWeekly.com and OC Weekly’s social media sites, Taylor “Hellcat” Hamby can be found partying like it’s 1899.

The lady who wrote this can’t put together a clear sentence to save her life. Go back to school or find a different profession.