There’s three things I remember most about the day I crossed the border as a seven-year-old child: Space Jam, the last movie I watched in Mexico in the smuggler’s house, a small figure of the Virgen de Guadalupe an old woman convinced the coyote to let her to carry with her, and a fear of drowning.

I had good reason for the fear. I nearly drowned twice when I was younger. The first time happened down the road from our house in Pantla, Guerrero when I got pulled into the water while playing on a river bank. The second time happened at a lake that formed right before that same river emptied its waters in the ocean.

But up until the moment my mom and I reached the river on the Mexican side of the border, I hadn’t considered our own personal danger in doing what we were about to do. I knew people died coming the United States. The last time my uncle Fernando had visited us from Texas he told us of a man who drowned in front of him on his previous crossing. And all the news reports of migrant deaths that I saw as a child in Mexico were about men drowning.

The fear hit me then.

We crossed on a Styrofoam raft that fit four people at a time. Each end was tied with a rope that the coyotes on both sides of the river used to pull it from one side to the other. I was among the first to get across stateside. Armando, a friend my mom and I had made during our stay in Tijuana, was in my group. Once we crossed, they made us wait on the slope of the river bank while everyone else made their way across. Armando held me with one arm, and clung to the grass growing on the slope with the other.

I told him not to let go of me over and over until we left the river.

Mom makes a point of quoting me every time she tells the story of our crossing. “Armando, no me vayas a soltar.” She does it jokingly, a bit mockingly, before she shares that that day was the second time she really felt fear.

Today, I hear very different news reports from those I heard as child. For immigrants in the U.S., last year ended in mourning for Jakelin Caal Maquin and Felipe Alonzo-Gomez, the children who died while in Border Patrol custody due to negligence and the agency’s long-standing disregard for human life.

There’s thousands of rosaries, saints, and virgenes scattered along the Southwest desert from past journeys. Hopefully, they light the way for new immigrants as they follow ever more dangerous routes to the U.S. in hopes of building different, better lives.

Hairo Cortes is a founding member and Executive Director of Chispa. You can usually find him singing along to Johnny Cash or playing with his cats. Follow him on twitter @HCortes96 for sporadic personal updates. Donate to Chispa!

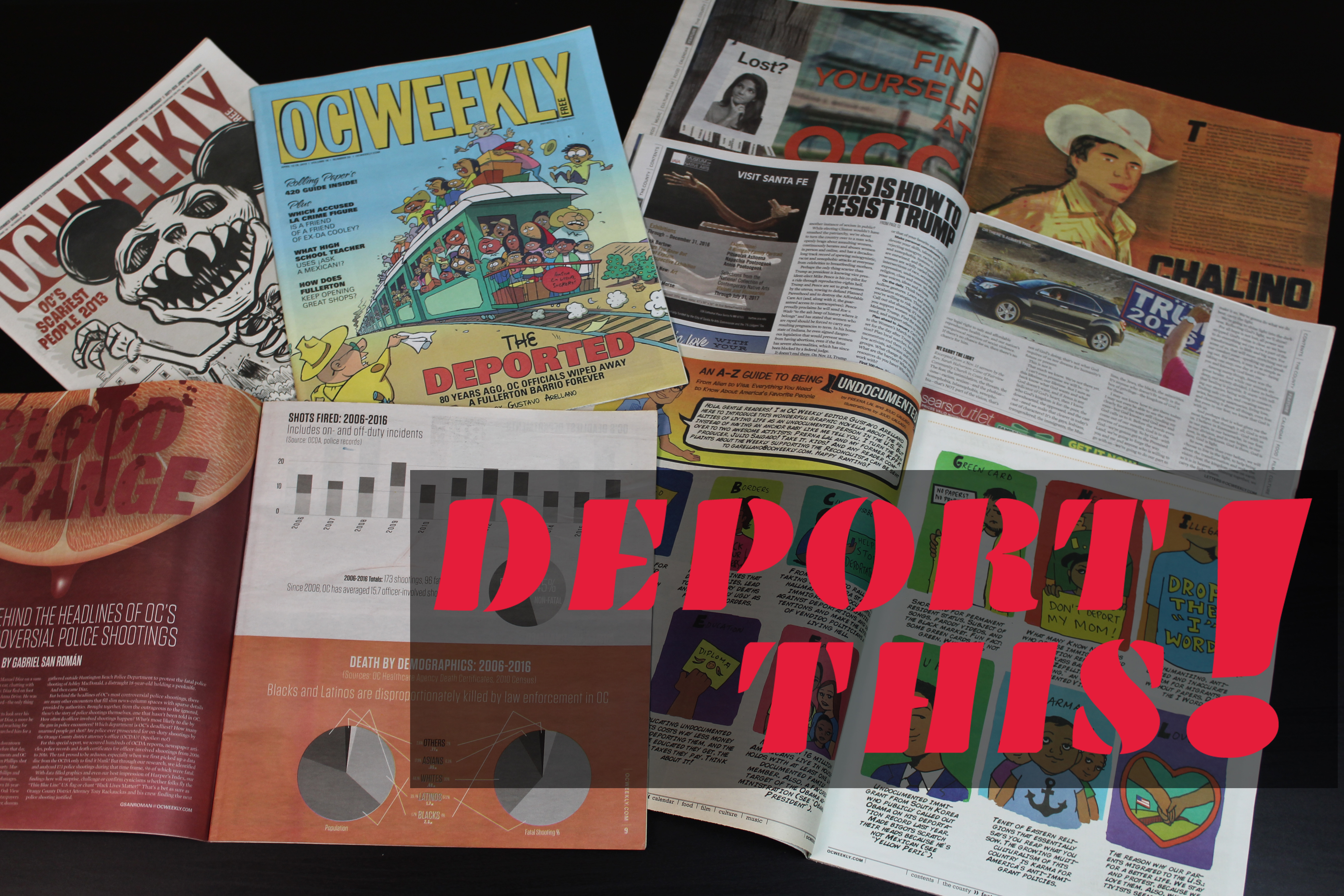

Deport This! is a partnership between OC Weekly, Chispa and Orange County Immigrant Youth United. The column is a rebuttal of Donald Trump’s racist politics and his OC cheerleaders, who’ll no doubt get triggered every week with news and views by and about the undocumented community.