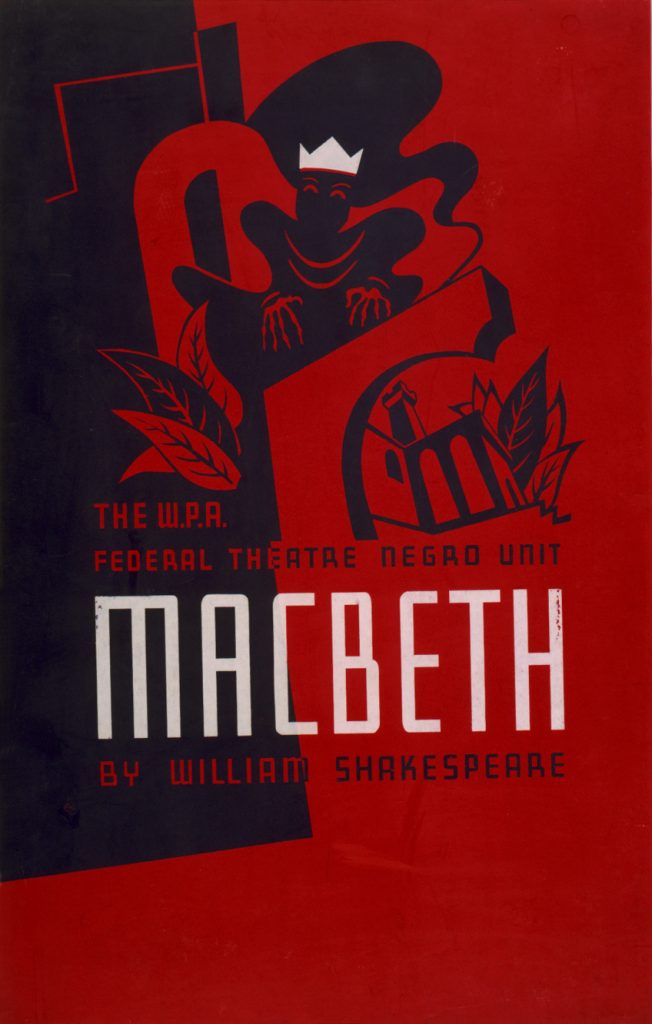

The poster is a very simple silkscreen job–virtually all red and black, with a bony-handed king perched atop the giant name “MACBETH.” Created in 1936 by artist Anthony Velonis, the poster was for the Federal Theatre Project’s New York production of William Shakespeare’s classic Scottish play, though with a few twists: the cast was entirely Black, the setting was the Caribbean, and the director was an ambitious 20-year-old named Orson Welles.

You can see this poster, and a few dozen others, in a new exhibition of public art at the Great Park Gallery in Irvine. Titled Federal Art Project: American Design, the exhibition explores a wide array of posters created for the Federal Art Project (FAP), an arm of the Works Progress Administration (WPA)–one of many relief agencies created to put people back to work during the Great Depression.

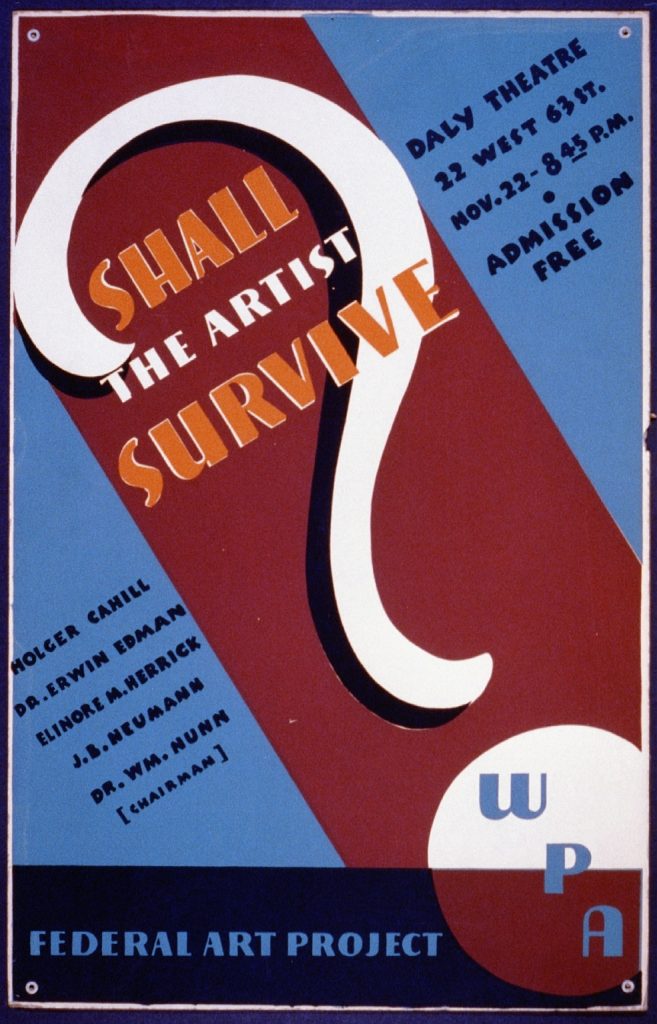

There are posters for coal miners in Pennsylvania, plays in New York, a print exhibition in Boston, and a photography show in Sioux City, Iowa. One poster for a New York play asks “Shall The Artist Survive?” Another advertises “Jobs For Girls And Women” in Illinois. Though most of the posters are realistic, a few can be quite abstract.

About 2,000 FAP posters are known to exist, according to the Library of Congress, and a little over 900 are kept there, though individual artist credit in many cases is simply unknown. Many of the posters on display in the Great Park Gallery exhibition have title cards that say “Artist Unknown,” meaning even the Library of Congress isn’t sure who created the work. Given that artists created these posters for the government, this isn’t too surprising.

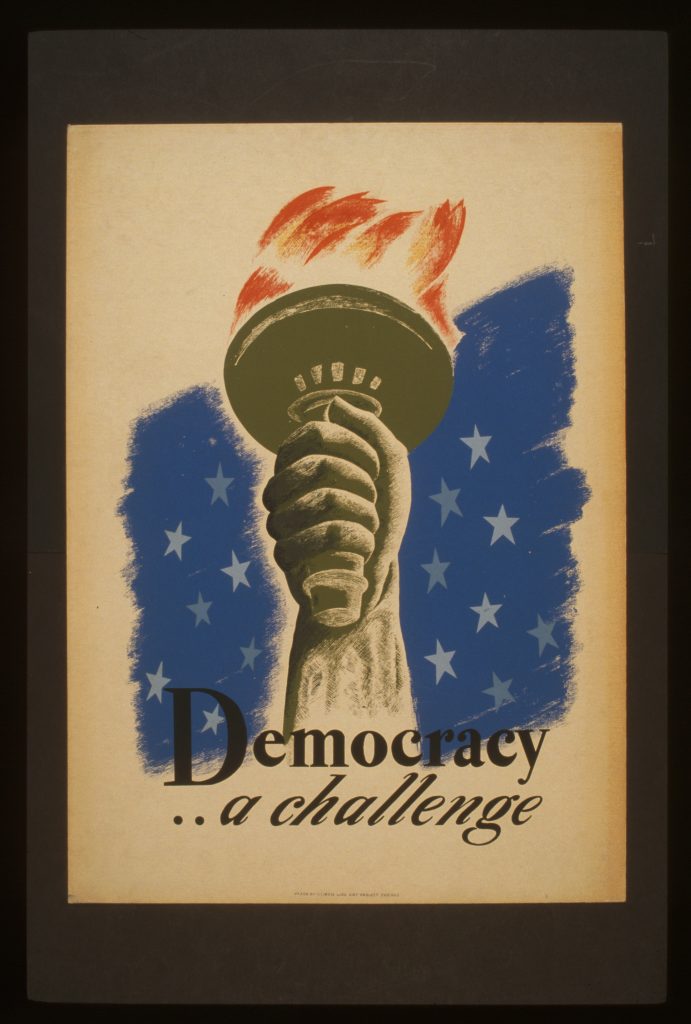

One striking 1936 poster from the New York Housing Authority from an unknown artist shows a menacing figure formed of dark, angular shapes with a hand wrapped around the handle of a pistol says you can “Eliminate Crime in the Slums Through Housing.” Another, also from an unknown artist, shows just the Statue of Liberty’s torch above the words “Democracy… A Challenge.” But the underlying message of all the posters is as clear as it is striking–the federal government thought so highly of art that it paid people to produce it.

“The whole idea of public culture that’s this far reaching has almost been banished from society,” curator Benjamin Cawthra told me. “Today, it’s controversial whenever the National Endowment for the Arts does something slightly left of center.”

Cawthra, a professor of public history at Cal State Fullerton, has been putting on exhibitions on this era for two decades. He did this show, he said, at the request of the gallery.

“Rural areas, and smaller metropolitan areas, didn’t have much access to culture,” Cawthra said. “It was a way to bring culture to these parts of the country.”

One of the biggest ways the WPA did that was through murals painted at local post offices. In fact, you can see one today at the old Post Office on Commonwealth in Fullerton. The untitled 1936 oil on canvas mural by Paul Julian–who later worked on Looney Tunes cartoons and even provided the famous “beep-beep” sound made by the Roadrunner–depicts a half dozen men and women picking oranges. The City of Fullerton’s website lists the mural as having been part of a WPA project, but doesn’t specify which one.

In any case, the whole point of the Federal Art Project wasn’t really the production of art. It wasn’t like today’s NEA–it was fundamentally a jobs program, created first and foremost to put people to work.

“Art was looked upon as a legitimate form of work,” Cawthra said. “It kept food on the table for hundreds of people. Steady employment, and steady income in the midst of a terrible depression. If we’re trying to put people back to work in this disaster called The Great Depression, [the Roosevelt Administration said,] then we have to fund the arts.”

And fund they did (though most of the FAP funds went to white males, Cawthra said he tried to highlight posters aimed at African Americans).

According to Jerry Adler’s 2009 Smithsonian Magazine article “1934: The Art of the New Deal,” the Public Works of Art Project–an early version of the FAP–“hired 3,749 artists and produced 15,663 paintings, murals, prints, crafts and sculptures for government buildings around the country” in the first four months of 1934. “The bureaucracy may not have been watching too closely what the artists painted, but it certainly was counting how much and what they were paid: a total of $1,184,000, an average of $75.59 per artwork, pretty good value even then,” Adler wrote (adjusted for inflation, that comes to $1,427.87 per work in 2018 dollars).

Given those figures, it’s probably not too surprising that many of the posters exude a kind of optimism–which is actually quite startling, given that the country was in really bad shape all the way through the 1930s.

“I’m not sure you’d realize there was a depression going on, given some of the posters,” Cawthra said, and he’s right. The posters are largely highlighting plays, classes, symphonies, travel. “It looks like functional society, but in the midst of a terrible economic meltdown.”

The artwork also shows a substantial faith in what was then popularly referred to as “the common man”–normal, ordinary Americans, who both understood the value of art and accepted it into their daily lives.

“The New Deal had tremendous faith in the powers of ordinary people to better themselves,” Cawthra said. “That they could rise above the difficulties they faced. People will get through this, if they just get a hand up.”

*

“FEDERAL ART PROJECT: AMERICAN DESIGN”

at Great Park Gallery, 6950 Marine Way, Irvine, (949) 724-6880; www.cityofirvine.org/orange-county-great-park/palm-court-arts-complex. Open Thurs.-Fri., 12-4 p.m.; Sat.-Sun., 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Through Feb. 10. Free.

Anthony Pignataro has been a journalist since 1996. He spent a dozen years as Editor of MauiTime, the last alt weekly in Hawaii. He also wrote three trashy novels about Maui, which were published by Event Horizon Press. But he got his start at OC Weekly, and returned to the paper in 2019 as a Staff Writer.

Some of the advantages to learning how to do stamped

concrete over an existing patio are that it can help to seal the edges

of the patio. This can be especially helpful

when sealing around a pool, hot tub or children’s pools. https://www.google.com/maps/place/?cid=10866013157741552281