The third Monday in May 2006 in Newport Beach was a beautiful day, even by Orange County’s springtime standards. An occasional, light Pacific Ocean breeze made the 70-degree temperature more pleasant under a royal-blue sky with good visibility. At the Marriott Hotel, eager, college-aged valets huddled near a gurgling water fountain and waited to park arriving luxury vehicles beneath a series of towering palm trees. Vacationing families and couples flocked to the outdoor pool. The big local question of the day: What to do about rowdy sea lions that boarded and almost capsized a sailboat in Newport Harbor?

But not everyone’s thoughts inside the swank Fashion Island hotel were on leisure and sea mammal antics. Four outwardly unremarkable, stern-faced men marched down a hallway on their way to a high-stakes drama. Though they controlled hundreds of billions of dollars, you’ve never seen them on a Forbes list. These men—who’d flown in from different parts of the North American continent—were members of the world’s most exclusive club, veiled in secrecy by the CIA, FBI, Federal Reserve, U.S Treasury Department and international banks. They often spoke in code, rarely met in person and only reluctantly told outsiders their names: William Joseph Ferry, John Brent Leiske, Alex Chelak and Paul R. Martin.

Like any truly secret society, details were shared only on a need-to-know basis. There were 18 members: six attorneys, six accountants, five bankers and a mechanical engineer. Half of them worked in the private sector, and half of them worked within the federal government. They had offices in Geneva, New York City, London and Hong Kong.

The organization was established in the early 1990s with two goals. It aimed to protect U.S. financial interests, specifically the strength of the dollar, from malignant foreign forces such as Chinese communists or Middle East terrorists, while exporting the notion of American exceptionalism by funding humanitarian projects around the world. Because of the sensitivity of their work, high-tech eavesdropping equipment on orbiting government satellites and undercover, federal agents on the ground monitored their daily lives.

They were enthusiastic, God-fearing patriots, as well as unapologetic capitalists. As a reward for their services, they took a financial cut—sometimes $100 million or more—from every project, whether it was in Ethiopia, Houston or Southeast Asia. By design, transactions were kept on the other side of a “curtain” from frontline IRS agents, tax-happy federal policymakers and snooping journalists. Members of this organization firmly believed in their righteousness, but they also worried about being exposed on 60 Minutes.

As they walked to the Marriott’s Emerald Cove conference room, these men—ages 46 to 64—donned the uniform of businessmen unable to completely relax: blue blazers, button-down shirts and khaki pants. The sweet strumming of a guitar playing Caribbean-style music on hallway speakers didn’t soothe anyone’s anxiety. They’d told George T. Tarpinski, the man they were meeting for the first time, not to bring his bodyguards because they weren’t bringing theirs. They were on the verge of a risky proposition: granting Tarpinski, a mysterious outsider, admittance into their secret world. But there was also substantial potential reward—more than $1 billion in cash was at stake, or, as they liked to say, “One B” or “One bravo.”

* * *

Tarpinski looked like Will Ferrell’s Saturday Night Live spoof of George W. Bush. In addition to wearing his short, dark-but-graying hair like Bush, the 52-year-old San Francisco native also shared his snort, smile and swagger. Tarpinski wasn’t a man who liked intellectual rigor. The fabulously rich investor favored golf over work, a preference evidenced by a deep tan. Whenever business negotiations turned hostile, he’d flash his toothy smile and crack a lame joke to break tension. Like the 43rd U.S. president, he was a cocky trust-fund baby.

At Stanford University in the ’70s, Tarpinski studied international affairs (there’s no record of his graduation) and, to hear him tell it, later began “aggressively investing” in California and international real-estate projects. Potential business associates couldn’t pry details from him, but his success was evident. He worked out of an office on a fashionable section of Pacific Coast Highway in Newport Beach, and though he didn’t like boats, his mansion overlooked Lake Tahoe in Nevada.

Tarpinski’s life had been carefully kept from public view. A Google search, for example, produced only his ties to a corporation, New MarMesa Group. It wasn’t clear, at least in obtainable records, if he was married or single. But based on his rugged face and the size of his wallet, he’d never had a problem getting dates.

Ferry, Leiske, Chelak and Martin knew two other facts. Tarpinski was one of the world’s richest men, and he craved more money, especially if future profits evaded tax implications. They’d also discovered that Tarpinski had a blazing temper when annoyed. Worried the group was trying to sucker him, he’d once yelled on the telephone at one of its Florida associates. The incident alienated the men, who toyed with the idea of rejecting his application before Tarpinski apologized.

But concerns lingered. In preparation for the Marriott meeting, the men insisted Tarpinski pass a background check by federal law-enforcement and espionage agencies. To help allay worries about his identity, he shared his American passport (#039620059) and transferred more than $1 billion—$1,000,399,934, to be exact—in cash into a Bank of America account in Los Angeles. When the men insisted on inspecting documentation of the transaction, he provided an official paper trail.

The background investigation revealed that no known criminal enterprises created Tarpinski’s wealth. If the two sides now could agree on a confidential deal, the billionaire real-estate developer would join an elite group that included “past [U.S.] presidents” (both Bushes), “the president of Italy” and the “royal family of Saudi Arabia.” They even bragged about ties to former Secretary of State Colin Powell and Microsoft founder Bill Gates.

But the group wasn’t a social club. It focused on making money. The men told Tarpinski that if they allowed him into their top-secret economy, he could expect annual interest payments “between 300 percent and 600 percent.”

Minimum to play? The group preferred clients to invest no less than $5 billion. In Tarpinski’s case, however, they’d agreed to a rare exception. He would see profits shortly after he put $1 billion in cash into a “deployment account” based in the Channel Islands off France.

It sounded farfetched, but they told the billionaire not to laugh. They encouraged him to rigorously investigate their credibility. “Do your due diligence,” they repeatedly asserted. They were, after all, smug about their successes. For example, they’d recently taken another investor’s $1 billion and rapidly turned it into $30 billion.

The investment opportunity should have sounded too good to be true. But then, as the criminal case that emerged from their meeting would reveal, so should the investor.

* * *

American history is replete with conspiracy theories about secret societies that wield enormous, unchecked, self-serving power over the U.S. government and world institutions. According to this mindset, unfettered democracy and capitalism exist only as a figment of mass delusion. Many of the theories espouse that elite men—it’s always men—control the affairs of nations for ultra-wealthy and highly secretive financial interests.

Dozens of books describe how individuals with insider knowledge of financial-market intricacies can, especially with at least tacit government approval, brazenly steal billions of dollars. One relatively recent case underscores that view. With federal agents watching but refusing to intervene, Bernie Madoff stole $65 billion during a multidecade Ponzi scheme that crashed in 2008—a fortune that largely remains missing.

At the core of the often-mystifying mix of government and banking is the U.S. Federal Reserve system, a 1913 Wall Street-inspired government creation that is controlled by individuals tied to elite banking interests and operated largely in the dark. Elected representatives of the people can summon a presidential-appointed Federal Reserve chairman to Congress to answer questions, but they have no power to alter his decisions. It’s also true that even minor Federal Reserve tinkering with, say, interest rates can have trillion-dollar implications.

In 2009, media outlets discovered that in the midst of the nation’s 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve secretly lent $1.9 trillion to well-connected corporations at a sensationally low interest rate of 0.01 percent. Fed officials deemed the transactions covert and therefore initially refused to provide details to the public. That stance prompted watchdog groups to blast the move as further evidence elites operate in a lucrative, clandestine world.

But U.S. government entities including the Treasury Department, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), FBI, and Department of Justice (DOJ) maintain that allegations of a secret, government-sanctioned economy are absurd. Treasury officials, for example, note that “fraudsters” seeking to steal investors’ money use “a mix of fact and fiction” to confuse potential victims about something that does not exist.

“There are no ‘secret’ markets in which banks trade securities,” declares one Treasury Department announcement on the topic of no-risk, high-yield investment programs. “Representations to the contrary are fraudulent.”

The SEC issued its own warning, advising investors to be extremely cautious if promised “astronomical profits and the chance to be part of an exclusive, international investing program” sanctioned by the Federal Reserve.

DOJ officials didn’t mince words either: “Such programs do not exist as legitimate investment vehicles.”

But despite strenuous government stances otherwise, the Fed’s enormous power and impenetrable operations make it an ideal villain for people who believe there is a parallel economic universe for elites.

* * *

In the days prior to their Marriott Hotel meeting with Tarpinski, the group reserved a specific conference room. Before the session, however, the front desk staff announced the room wasn’t available. The group was switched to another location, the Emerald Cove room.

This third-floor room is at the farthest corner of the hotel from the lobby and at the end of a narrow hallway. No passing foot traffic guaranteed privacy. If the last-minute switch frustrated the men, they didn’t suspect anything odd.

The Emerald Cove room has the best perch of any conference facility in the hotel. The view allows occupants to conduct business while overlooking a hilly, lush golf course. A bit farther but less than a mile away, they could see multimillion-dollar beachfront homes and the sparkling, blue Pacific Ocean.

The alluring sights helped ensure nobody noticed a high-tech, pinhole camera and microphone had been installed at about belly-button level in a bookcase less than four feet from the picturesque window. Someone in another location controlled the camera, including the ability to pan the room, by remote control. The moment Tarpinski and his personal assistant, Will Edwards—a suspicious man with an NFL tight end’s physique—entered the meeting, every word would be recorded.

* * *

Richard Arthur Pundt knows all about surreptitious surveillance. He is a former FBI special agent, but his demeanor lacks any hint of law-enforcement swagger. He’s a good-natured fellow who enjoys sitting for hours in a coffee shop and talking and laughing with anyone willing to strike up a conversation.

That’s not to suggest Pundt is an empty suit. A former prosecutor and local Republican Party chairman, he owns Enlighten Technologies Inc., an Iowa-based government-contracting firm that supplies secure video-conferencing services for confidential gatherings. His close friends include men who’ve served as U.S. marshals, state judges, FBI agents and state attorney general investigators. He’s even pals with a high-ranking member of INTERPOL, the France-based international police agency focused on organized-crime syndicates. Given his extensive law-enforcement ties, Pundt should easily spot a con game and the crooks who run it. Indeed, the 67-year-old Cedar Rapids resident has been known to issue warnings that confidence men are constantly devising schemes to steal gullible people’s money.

In May 2006, Pundt flew first-class from Iowa to the Newport Beach Marriott and told Tarpinski that if he put $1 billion in cash into a special overseas bank account, he’d enter a private but government-approved club.

Protective of their boss, Tarpinski’s staff recorded Pundt during an earlier phone conversation. “I know there are people running around saying there is no such [secret society],” he said, according to a transcript obtained by OC Weekly. “Well, they are wrong.”

Pundt explained that the Federal Reserve and CIA primarily regulate the secret, “bona fide” investment program that is only “open to very elite people.”

In another conversation, he said, “This whole business—getting to the right people—is who you know and the right contacts.”

Is the ex-FBI agent misguided? Or is he privy to explosive insider information? Is it possible federal agents and businessmen could devise a secret world and mask its existence?

Two acclaimed Washington Post reporters may have answered that question. In early September of this year, the Post‘s Dana Priest and William M. Arkin published “Top Secret America,” touted by PBS’s Frontline as “a two-year examination into the massive, unwieldy top-secret world” constructed by the federal government after 9/11.

Priest and Arkin describe how Americans are kept in the dark about new government agencies’ missions, locations, employees and budgets, as well as the identities of private subcontractors. Even the names of the agencies aren’t publicly known. According to the reporters, nowadays, not even top national-security advisers to presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush have known who is doing what in the name of national security.

* * *

“The best way to attack the United States is through attacking the dollar,” John Brent Leiske of Oregon told Tarpinski when the Emerald Cove room meeting began. “[The terrorists] have learned that since 9/11.”

With his back to the picturesque view, the 46-year-old, obese Leiske sat at a white-cloth-topped, U-shaped table arranged with filled ceramic coffee mugs and Fiji water bottles in front of the six attendees, including Tarpinski, Edwards, Martin of New Jersey, Chelak of Canada and Ferry of Corona del Mar. The soft-spoken Chelak controlled the group, but he preferred that Leiske, the youngest and most animated member, lead the presentation.

After rolling up the sleeves of his pink button-down shirt, Leiske assured the billionaire that he’d gotten this far in his application to join their “rare group” because “you’re not involved in any type of blowing up a place or anything like that.” Martin and Ferry chimed in that while they’d worked with Asians and Arabs, they preferred deals with Americans. Tarpinski listened silently.

“So who are we?” Leiske continued. “Are we a big institution that has a shingle outside, trying to attract clients to come in and do transactions with us? No. . . . We are people behind [joint government/private efforts] that want to keep the U.S. dollar strong. . . . We try to design transactions to assist the U.S. dollar.”

According to Leiske, his group owns a secret “financial patent” sanctioned by the government. That patent allowed them to use a select person’s assets as credit in a hidden economy that produced rapid, astronomical profits with no tax liabilities. To stifle detection, account names were routinely altered and money constantly shifted between Asian, European and American markets.

There were, of course, conditions to access this world. Tarpinski must sign a written contract with mostly non-negotiable terms. One item was a strict confidential agreement. “If you go and share this information, no one’s going to believe you,” explained Leiske. “We do want to keep it private, but that’s to keep you safe and us safe.”

Tarpinski would also have to share his windfall. After a 1 percent to 5 percent transaction fee, remaining profits from his $1 billion investment would be split 50-50 between him and a World Bank-approved humanitarian project.

The billionaire had already made it clear he thought the humanitarian angle was ridiculous, but not enough to dampen his interest. Leiske and his colleagues had sized up Tarpinski as a man motivated primarily by greed. To put a fine point on his pitch, Leiske added, “You put up one [dollar], you get back six.”

But Tarpinski would never be allowed to learn precisely how the profits were made, except that the group had “privileges” with Treasury officials based in Philadelphia, as well as inside the upper ranks of the CIA, Federal Reserve, World Bank and FBI.

“There’s a curtain that will be drawn across this transaction, and you, frankly, will not be on the other side,” Martin told Tarpinski. “So, basically, what goes on in that box—even though you don’t know what it is—it’s not going to bite you.”

If they wanted to assure Tarpinski that his money was safe—that it was almost impossible to lose a penny—they also wanted him to know he was lucky. They told him they didn’t want to offend him, but his billion-dollar investment was relatively small. They said their prior “70 to 80” operations involved more than “$1 trillion” and had left them with “$600 billion” and accumulating another “$500 million a week.”

No fool, Tarpinski played his card: “Why do you even need me?”

Martin responded, “You’re the fresh money!”

A more-cautious Leiske added, “Because we cannot use our own funds. . . . You work like a spark plug, where you allow us to get our notes created. . . . You’ve given us permission to use our own funds.”

Martin then advised the billionaire that rules governing these secret transactions forbade the group from putting its own funds back into circulation. The group claimed it made so much money so quickly that an infusion of those funds into the “retail economy” would cause massive inflation.

“Regulators don’t like that,” Martin said solemnly.

Tarpinski accepted the explanation.

* * *

FBI Special Agent George Steuer appreciates a good story just as much as anybody else. But Steuer hasn’t hidden his intentions to influence Hollywood films and television shows. In 2007, he helped conduct an unusual government workshop at the Federal Building in Westwood: “Crime Essentials for Writers.”

The workshop was designed to address a problem that has long flustered the FBI: its portrayal in fiction as bumbling or corrupt. Such concerns originated with legendary FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s determination that agents must be cast as heroes. Hoover spied on Hollywood studios to ensure they complied.

The agency’s sensitivity extends to modern times. In 2006, for example, the FBI participated in the development of 649 films and TV shows. Steuer even grabbed a gig as consultant to the 2008 law-enforcement thriller Untraceable.

The agent knows thrillers firsthand. From August 2005 to April 2007, he got assigned to a secret, Southern California-based, law-enforcement task force created to expose financial shysters targeting wealthy Americans. Prosecutors at the DOJ in Washington, D.C., and at the Ronald Reagan Federal Building in Santa Ana directed the project, code-named “Collateral Monte.” Fellow FBI Special Agent Norman D. Embry joined Steuer. Earlier in his career, Embry won accolades for posing as an employee at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago to expose thefts by baggage handlers.

In their California operation, Steuer and Embry went deep undercover with false identities.

Steuer became investor George T. Tarpinski.

Embry became his assistant, Will Edwards.

They established a dummy corporation, New MarMesa. They laid bait by publishing a Jan. 25, 2006, advertisement seeking high-end investment opportunities with little or no risk. Then they waited.

About 13 days later, Pundt—the ex-federal agent—and another man contacted “Tarpinksi” and “Edwards” and vouched for the secret investment program. According to a transcript of the phone call, Pundt claimed he’d been involved in the operation for “nearly four years.” He stressed that only select individuals were allowed to participate, adding that someone would “have to be a complete idiot” to lose money.

But first, said Pundt, Tarpinski’s identity and net worth would have to be verified by Chelak, whom he said “works directly with the CIA.”

* * *

After four hours of face-to-face discussions with “Tarpinski” and “Edwards,” Leiske and his colleagues had grown noticeably impatient, according to audio and video surveillance of the meetings that haven’t yet been made public but have been exclusively reviewed by the Weekly. They wanted Tarpinski to sign the contracts and put the $1 billion into the new account. An unconvinced Tarpinski insisted on more assurances, especially about risk and taxes.

“There will never ever, ever, ever be a legal, direct, dotted-line nexus between your funds and the monies that’s [sic] deposited in the profit accounts,” said Martin. “That’s deliberate.”

Everyone in the group assured Tarpinski that he would never lose control of the $1 billion.

Said Leiske, “We have it in your control.”

Added Martin, “Nobody can put their hands on it.”

“The 1 billion would never come out of [your] account,” said Leiske.

“This is a monetary world where the Central Bank of the United States is actually using your funds to manage the creation of money,” said Martin.

Then Leiske described how Tarpinski transferring the $1 billion from his Bank of America account in LA to the foreign account was like moving the money from “your right pocket to your left.”

Chelak rarely spoke, but he felt the need to note, “There’s a lot of people who say that they can do things, and what happens is they take your money. And basically, what [Leiske] was covering there was they want you to move money into their accounts. I’ve heard a lot of horror stories.”

At the end of the afternoon session he attended, Pundt declared, “Well, I like everything I’ve heard here.”

Shortly thereafter, Tarpinski agreed to the deal. Contrary to repeated assertions otherwise, the fine print gave Chelak authority to use the $1 billion at his discretion once it landed in the Channel Islands.

* * *

Whatever elation members of the group felt when Tarpinski signed the contract that day in Newport Beach, they were ultimately disappointed. The undercover agent never transferred the cash. He was stalling. In July 2008, a federal grand jury filed fraud and conspiracy indictments against the men.

Agents arrested Leiske, Martin, Pundt, Ferry and several of their alleged associates who didn’t attend the Marriott Hotel meetings: Ronald James Nolte, Dennis J. Clinton, Brad Keith Lee and Joseph T. Schuck. (The entire operation netted more than two dozen arrests.) Everyone has pleaded not guilty, except for Lee and Schuck, who signed guilty pleas and were sent to prison for 24 and 12 months, respectively. Chelak remains a fugitive.

Leiske, Chelak’s understudy, is also facing federal charges in Oregon for allegedly defrauding more than $5 million from Billy Bernard Britt. According to that indictment, Leiske claimed his clients included George and Barbara Bush, and he was a gatekeeper to a secret economy. Britt, a famous Amway executive, believed the pitch.

Federal officials were not amused, however. For all of his supposed assets worth hundreds of billions of dollars and high-level spook access, Leiske didn’t even own a home, FBI agents discovered. Presently incarcerated, he is scheduled to face trial in the Britt case in January 2012.

The Tarpinski matter—delayed four times by defense lawyers—is set to begin in March 2012 in U.S. District Judge David O. Carter’s Orange County courtroom.

* * *

There are three possible interpretations of what happened in the FBI sting. One is that federal prosecutor David A. Bybee is right, and the defendants fabricated a scheme based on the false existence of an underground economy. Or the defendants are right, that they are scapegoat gatekeepers to a clandestine world that won’t rescue them now that they’ve been exposed. Or, lastly, the defendants are shameless schemers, and incidentally, there is a secret, government-sanctioned economy that doesn’t include them.

Perhaps the key to the answer is Pundt, the ex-FBI agent with all the high-level government pals. He was a central villain in Bybee’s original scenario of the crime. Pundt sold the fake billionaire key details about the deal and vouched for its credibility. John D. Early, Pundt’s defense lawyer, said his client “believes this stuff.”

Pundt, who faced 10 federal charges, declined to be interviewed but said in an email to the Weekly that the FBI and DOJ “initially acted precipitously and without regard for the actual facts of case.” He called the sting “nothing short of outrageous.” He also said the agents should be held accountable for their “wanton and reckless” conduct.

At a 2009 pretrial hearing, Bybee emphatically objected to Early’s motion to excuse Pundt from the case.

“It is Mr. Pundt who is taking his directions from other co-conspirators in the case,” the federal prosecutor argued. “He does his best to see that [Tarpinski transfers] $1 billion into an account the conspirators control.”

Yet on Aug. 4, 2010, Bybee flip-flopped, writing in a terse court filing, “New circumstances have come to light such that the United States seeks to dismiss the indictment against Mr. Pundt without prejudice in the interests of justice.”

Bybee didn’t say the sting investigation erred. He didn’t outright call Pundt innocent. His moves created another mystery.

According to multiple sources with knowledge of the case, top-level DOJ officials met in a closed-door Washington, D.C., session and decided to release Pundt. He held a press conference in Iowa, declared himself “completely exonerated” and thanked U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder for intervening. At the event, he said nothing more about the existence of a government-sanctioned, hidden economy.

(Pundt declined the Weekly‘s request to explain his beliefs on the topic.)

DOJ officials claim the “new circumstances” that came to their attention are state secrets. That part of the Tarpinski file has been sealed. Not even the lawyers for the remaining defendants know what information it contains.

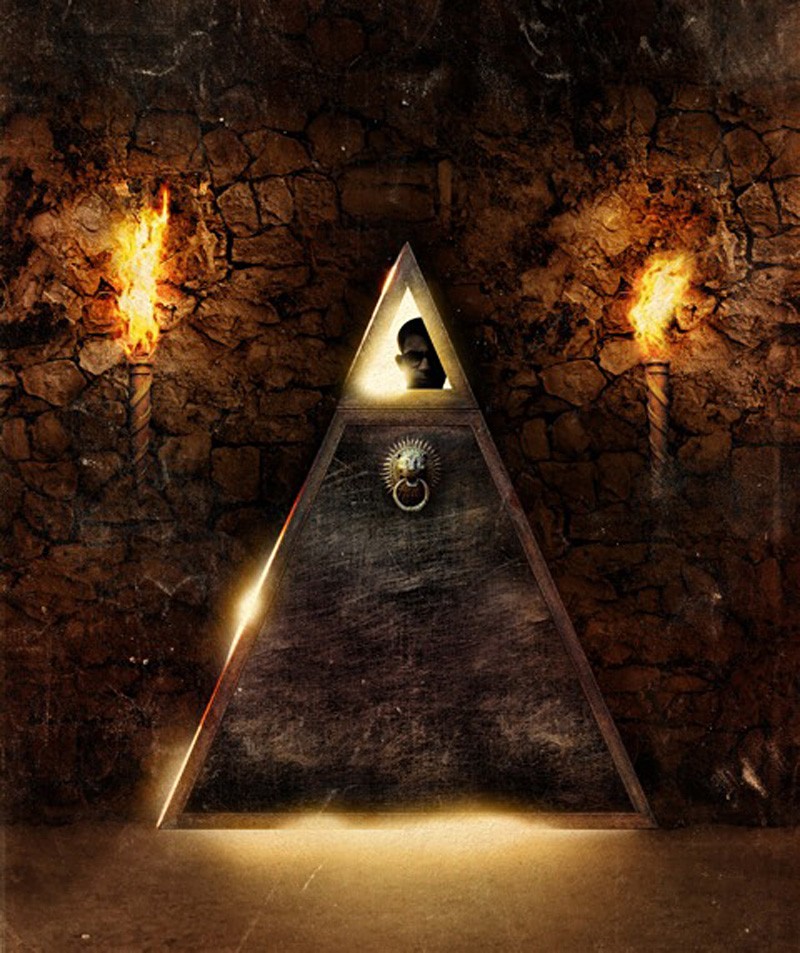

This article appeared in print as “Pyramid Scheme: Men boasting CIA and FBI ties met in Newport Beach to convince a mysterious billionaire to buy into a secret economy—and nothing was what it seemed.”

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.

I’m in love with the cbd products and https://organicbodyessentials.com/products/cbd-capsules-25mg ! The serum gave my peel a youthful support, and the lip balm kept my lips hydrated all day. Knowing I’m using moral, simpleton products makes me desire great. These are now my must-haves after a fresh and nourished look!

I recently tried CBD gummies from this website https://www.cornbreadhemp.com/collections/cbd-cream for the prime control and was pleasantly surprised past the results. Initially skeptical, I create that it significantly helped with my appetite and slumber issues without any notable side effects. The oil was easy to utter, with clear dosage instructions. It had a merciful, vulgar grain that was not unpleasant. Within a week, I noticed a signal upgrading in my overall well-being, ardour more relaxed and rested. I comprehend the regular approximate to wellness CBD offers and plan to at using it.