Fittingly, Thomas K. Brimer gets pretty jumpy. The lean, somewhat-bombastic sixtysomething surfer with the shaggy mop of blondish-gray hair and thick, black-framed, Coke-bottle-thick glasses moves about a mile a minute through the aisles of TK’s Froghouse Surf Shop. As he stealthily maneuvers the rows of wetsuits and surfboards at his store, which has survived on Pacific Coast Highway in Newport Beach since 1962, his head bobs from time to time above the racks of rash guards and surfboards. He fields questions from every direction, before leaping toward the storeroom to disappear.

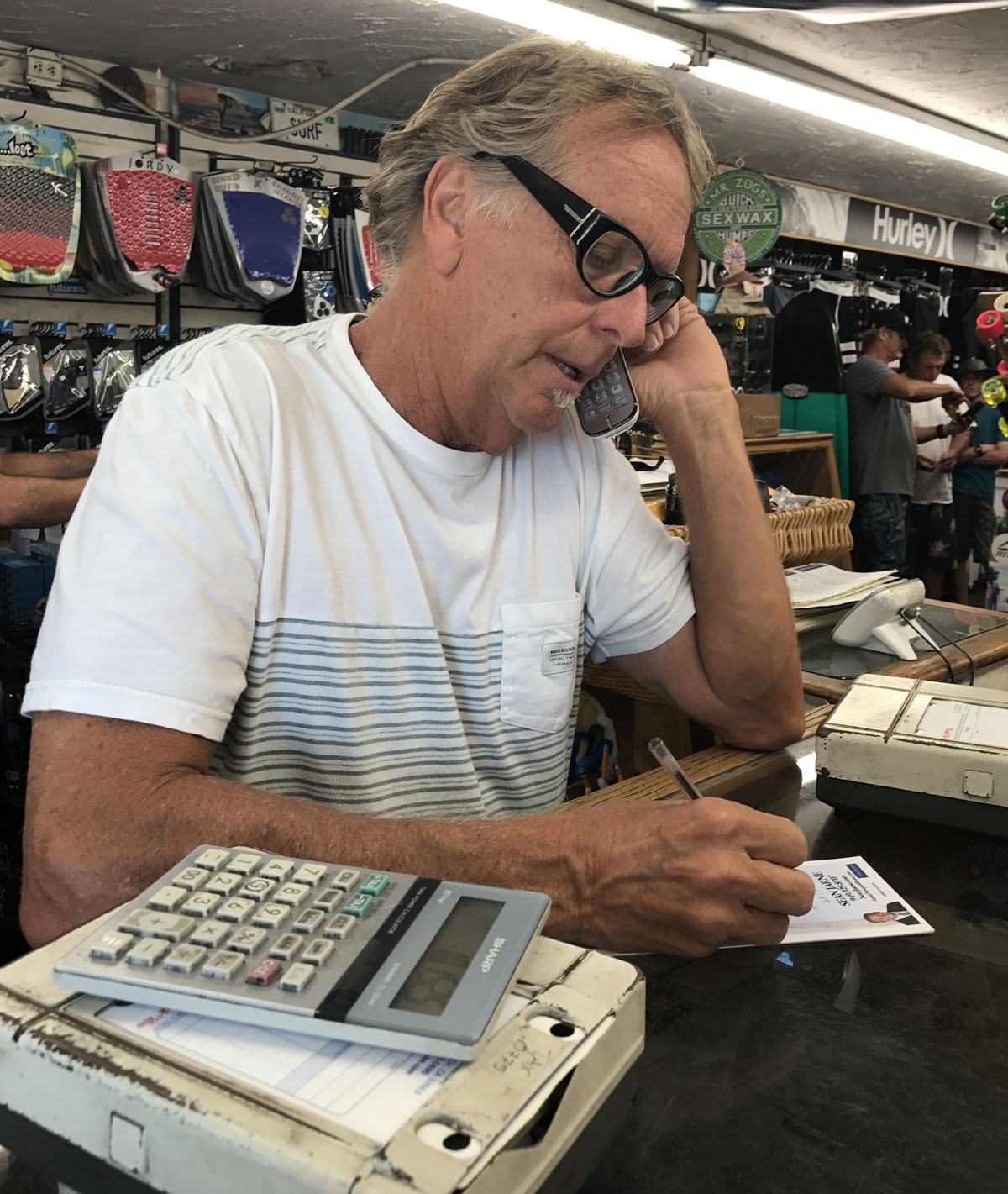

When he re-emerges, he has good news: The thingamabob is in stock. The phone rings. “Teeee-kaaaaay!” one of his shop guys, Zack Leonard, yells across the crowded shop before returning to banter with a grom mom buying a new wetsuit for her son. A finance guy is on the other line with some sort of pitch. “Oh, here we go,” Brimer says to everyone and no one at once, with an air of resignation and exasperation.

“We are a small shop,” he tells the guy in a tone that lets everyone present know he’s about to preach his Tao. “I have about 10 checks to sign a week.” Call the big guys on Main Street, he says candidly. “They’ve got hundreds of employees!”

Froghouse sits on the north side of PCH on Newport’s Westside, the less Housewife-y section of town across from 56th Street and the Santa Ana River Jetty. Sand is caked in every crevice of the storefront, with its legendary frog mural on the side. A distinct fragrant blend of neoprene and epoxy resin with base notes of Mr. Zog’s Sex Wax perpetually hangs in the air. It’s faded, crusty OC with characters out of a Rick Griffin panel, a very different Newport than today’s slick version.

But there are few throwbacks like Brimer, who only occasionally visits our modern world. Journalists nowadays mostly use email to get in touch with potential story subjects, maybe send a Facebook message or get a cellphone number from a friend of a friend to call or text. Not with Brimer. Try to get information from Froghouse employees on his whereabouts, and they’ll direct you to the carbon-copy message pad that sits on a glass display case. Brimer’s social media is solely for others to post pictures. He rarely uses a computer other than to check the few emails he receives on his AOL account.

A cellphone is like an “electronic leash,” Brimer explains when we finally meet face to face. And that’s the only way to meet: You have to hope you run into him or catch him at the shop when he hasn’t come up with an excuse to go surfing.

This Luddite life is part of what has maintained the same Froghouse vibe since original owner Frank Jensen seized on the newfangled surfing craze by opening a store that catered to the half-clothed teens flanking the shoreline. Not a surfer himself—he didn’t even know how to swim—Jensen named his shop after a Big Kahuna type nicknamed Frog. It’s one of the oldest surf palaces in OC, with Jack’s Surfboards on Main Street in Huntington Beach claiming the legacy title. But shops such as Jack’s and Hobie’s today bear no resemblance to their original incarnations, unlike their Newport peer.

With mainstream brands co-opting the surf culture to get their share of what Global Industry Analysts estimates is a $13.2 billion industry, most shops have grown into Sears-like megastores, with the vast majority of inventory being soft goods—what lay people call “clothes.” Froghouse flips that shop ratio, refusing to cater to a wider audience that doesn’t wax regularly. But despite the limited inventory, the shop buzzes all day, with locals stopping in, junior lifeguards picking up fins, shirtless-and-shoeless surfers tracking the elements through the door, and the occasional old friend or longtime customer making a surprise appearance.

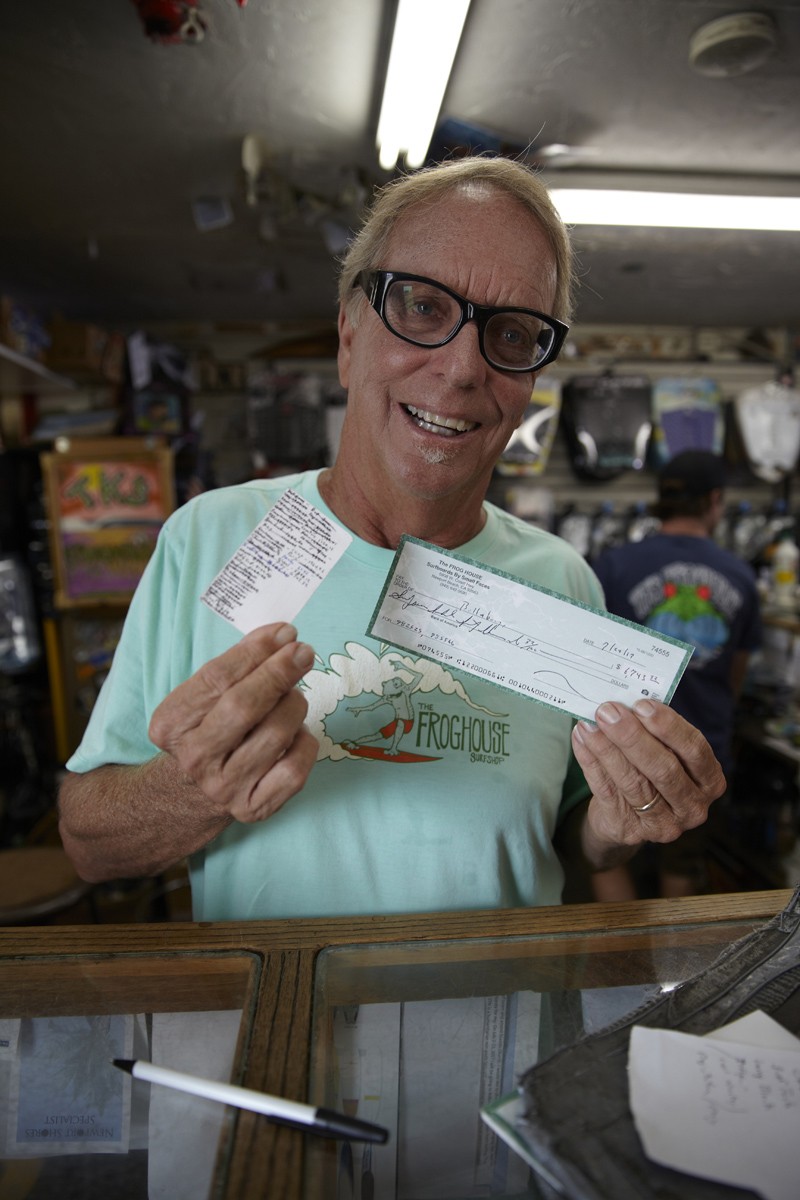

And every night, Brimer takes handfuls of handwritten receipts home to his wife, Linda, to tally and record.

“It’s like a drug house for surf shit,” said Weekly photographer John Gilhooley after trying to track down Brimer for weeks, which resulted in the outdoor-shower shot you see here (his shop guys goaded him into doing it). But it’s also not a bro zone in an era in which surfers become more and more clannish and suspicious—even mocking—of outsiders. “I always thought, ‘If I am ever in a position to have my own surf shop, that’s not how I would treat people,'” Brimer says. “We are an itty-bitty surf shop surrounded by big-box surf shops. We have to be different.”

* * * * *

For Brimer, surfing took hold as a 12-year-old in Titusville, Florida, population 10,000, about the same time Froghouse opened its doors. He was immediately smitten, even if he considers himself late to the game. “Florida was about 10 years behind California when it came to surfing,” he says. He spent most of his days chasing waves with his friends Richard and Steve Alexander, cruising in a Dodge convertible along the Atlantic coast with the brothers’ long, red surfboard (which they all shared) sticking out the back. Brimer got a gig blowing up beach mats to save up and buy his own.

[

Impatient even then, the teen asked his father for a $140 loan—big money in those years. Instead, his levelheaded dad drove him to the bank and co-signed for a loan. His payment-ticket book broke it down—the monthly payments, the interest rate translated to cash dollars, and the extra he’d pay if he stuck to minimum payments. “It was shocking to me,” he recalls, especially for a kid mowing lawns at $3 a pop. He worked hard, paid off the loan early, and promised himself he would never again buy anything on credit other than real estate or businesses. He still hasn’t.

In 1967, Brimer’s rocket-scientist father transferred from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station to McDonnell Douglas in Huntington Beach half-way through senior year. Brimer happily headed West, and Surf City became a natural home. Once settled, he met Charlie Ray, who surfed with the Froghouse team. “I walked in the front door, and it was the surfiest surf shop I could have ever dreamed of,” Brimer says, the memory still fresh. Jensen’s favorites helped themselves to beers from the in-house keg as they compared notes on local girls and waves. “I thought, ‘If I could belong and be an insider with these guys, then who could be against me as I made my way into the lineup in the local surf breaks?’ I wanted to belong, and this was my chance.”

Impulsively, he pleaded with Jensen for a job that wasn’t available. After a few weeks, Jensen asked Brimer to work Saturdays, which was about five days a week less than he was already toiling away for free. And for the next 10 years—save for a seven-month trip that saw him surf through Panama and nearly settling down to a life of full-time surf-bummery in Costa Rica—Brimer worked at the Froghouse, eventually becoming manager. A side hustle buying and selling properties allowed him to save cash and approach Jensen with a proposition: Either he sell the shop to Brimer for $100,000, or Brimer would start his own near Bolsa Chica and compete. Jensen agreed to sell.

Brimer couldn’t help but haggle, though. They agreed on $100,000 for the business—but that didn’t include inventory. Brimer only had $60,000, so Jensen financed the remainder over 10 years. They came to an agreement on the finance rate, and then Brimer appealed to Jensen’s love of gambling. Froghouse hosted regular all-night poker sessions, so they played three hands of five-card low, a shop favorite. Each hand Brimer won decreased the percentage rate by 0.25 percent. Brimer got lucky—and an even sweeter deal.

That still wasn’t enough. Brimer also wanted the option to buy the property, which included the store, a small house and the lot below. Jensen, known as someone unafraid of coming off as difficult, wasn’t interested. “Well, would you sell it for $50 million?” Brimer asked, with a grade-school “huh?” thrown in at the end.

It was, of course, a ridiculous question about three lots in Newport in the 1970s. Jensen begrudgingly admitted he would.

“So, then you will sell it,” Brimer replied with some snark, determined to wear him down no matter the starting point.

He convinced Jensen to add an option that allowed him to buy the property for $450,000 at the end of his 30-year lease. By the time the lease expired in 2008, its market value was $850,000. Jensen honored the deal. “I came out smelling like a rose,” Brimer says through a satisfied smile years later. If he had to rent, that could easily cost $10,000 per month. That cushion allows Brimer to stay true to Froghouse’s roots.

* * * * *

“I don’t want to be one of those rich surf-industry types,” Brimer says. He turns down offers to add more locations because he doesn’t need to sell out to survive or even thrive.

“My competitors don’t like me sometimes,” he says, referring to his sustainable overhead that translates to competitive pricing and coveted bro deals. Besides, he’s not into capitalizing on surf culture in an inauthentic way. “The surf industry used to be about lifestyle,” Brimer says, wistfully recalling the days when shop owners closed up on Wednesdays and went surfing instead of selling boards. These days, the biz is too cutthroat for such camaraderie.

“What we call the surf industry now is really the clothing industry,” Brimer says. “What bothers me is all the kids who will grow up never having gone in a real surf shop,” he says before looking off toward the ocean, through a wall with no window, lost in thought.

[

The Froghouse pretty much operates the same as back when Brimer traded a surfboard to an artist for the store’s logo, a surfer in a barrel coming out of a frog’s mouth. That logo is one of the reasons the shop’s T-shirts are so popular with purists. It’s also because Brimer finally thought to take them out of the cabinets some years ago so people could see them. There is no computer, no electronic inventory. The cash register doesn’t work, and the only guy Brimer knows who can repair it died a few years back.

Brimer’s list of contacts in the surf industry amounts to a long, worn-out piece of paper taped to the front of the broken register. Peeps usually call him when it’s time to pay up, for which he pulls out an honest-to-goodness checkbook and handwrites a check for thousands.

The function-over-form store layout is a little intimidating to the average Joe or Jane, especially with its inside-joke thingamajigs, irreverent signage and vintage photos of surfers hanging from every square inch. A mounted, cartoonish shark head akin to the one in Jaws watches over the dressing rooms. Vintage California license plates alternate between surf- and Froghouse-related paintings people gifted Brimer over the years. A sale sign promotes “gluten-free, cage-free, hormone-free” tail pads. A Best Surf Shop trophy with a naked Ken doll atop posed like Burt Reynolds in a Playgirl centerfold cozies up to the skateboards. A taxidermied mountain lion wearing a top hat hangs next to a childhood photo of Brimer with his signature thick, black glasses already defining his fashion sense at a young age. It all looks like it could be Brimer’s garage, where he rents boards to passersby.

The trade-off is that he doesn’t have to pass on any remodeling costs to customers—or even general maintenance beyond the occasional shop guy running a vacuum through the place. “If you’re going to shop in a place that looks like this, you should at least save a buck,” Brimer says, as customers stream in.

Besides, if customers who frequent any of Froghouse’s real competition actually surf, Brimer has a secret weapon. His is one of the only local surf shops left that offers wetsuit repair, so competitors often refer people to Froghouse for their stitches. That gets new, potential return customers through the door who may have otherwise passed by. It’s still more shop than store, with tools around for ding repair and a messy storeroom with two vintage, industrial Chandler sewing machines bookending the small workspace.

“Surf shops are a part of surfing that is becoming lost,” Brimer says again. “People can get hooked on it still, but it’s just not the same.”

Yet, the Froghouse manages to not only hang on, but also ride out the industry’s ebbs and flows. The shop broke its all-time sales records during the past three years because “people are still surfing,” Brimer says. This year is on track to be just as good, and he’s as surprised as anyone else. But he knows sales are cyclical, so he keeps a diverse investment portfolio to absorb any dips. He even owns a Jack-in-the-Box in South Carolina.

But some things are hard to predict or prepare for. In July 2010, the city of Newport Beach issued Brimer a notice to abate his building. After 48 years as a city landmark, he found out Froghouse was not zoned for commercial use and that he had 90 days to relocate or apply for rezoning. He had become victim to the city’s urgent quest to rid itself of sober-living homes by going after business owners working out of residential properties. Back when Jensen opened the business, the city basically looked the other way with the caveat that he never switch the type of business operating at the location. But that changed.

It wasn’t just Brimer who felt the sting. Generations of Froghouse faithful fought back. Someone started a Save the Froghouse Facebook page, which garnered 17,000 likes within days. A former customer named Larry printed up thousands of high-quality, laser-die-cut “Save the Froghouse” stickers to pay back Brimer’s kindness from when he was an aspiring pro surfer in the 1980s. Someone else sent hats with the same slogan. Two other regulars who owned a land-use company tutored him on how to navigate the building and planning department, as well as how to get the city manager to admit that Froghouse was a “non-intended consequence” of the sober-living ordinance. An architect gave him drawings for gratis, and an attorney pitched in services pro bono.

Community members wrote letters to the city, adding personal stories about how Brimer was more than just a quirky shop owner. He was the guy who hires homeless people to paint a new mural on the backside of the shop to put earned money in their hands. The guy who volunteers with fellow church members at a summer camp for foster kids. The one who loans an employee money to fix his car without batting an eye.

[

“It was kind of uplifting,” says Mikey “Beho” Flores, Brimer’s best friend and a Froghouse employee since the day Brimer bought the shop.

Once the issue made it onto the Newport Beach City Council docket, the troops rallied. So many people showed up to the council chambers—from Bob Hurley to parents to local surfers who had never cared for local issues yet showed up with speeches—that it was the first item the council addressed, lest everyone stay up late. A waiver to save the Froghouse passed unanimously. “It was like the scene from It’s a Wonderful Life,” Brimer says, still touched.

* * * * *

If you’re trying to track down Brimer on any given day, he will most likely walk into Froghouse mid-morning and immediately leave for a surf sesh with Beho before returning to pick up messages, take care of business and get his employees something to eat. In his mind, it just makes more sense to buy the tadpoles lunch and deliver it yourself in your decades-old, rusty, oxidized, silver Volvo wagon with as many stickers plastered on its every inch as a Wahoo’s. That way, he doesn’t have to deal with scheduling lunch breaks, especially since employees each get a paid surf break most days, too. The most complicated part is where they will get lunch from, which comes down to the winner of a game of airborne tiddlywinks headed toward a specific “H” on the Hurley-logoed carpet. There are do-overs, tape measurers, judgment calls, but it always remains amicable. The winner chooses which lunch menus to pull out of the drawer, and lunch is served behind the counter.

No one has more fun than he does, Brimer jokes. He even makes time to volunteer every summer at the Orange County Fair to make waffle cones in exchange for a season pass and some prime people watching.

His 36-year-old son, Dane, however, wanted to put his MBA to use at the family biz and focus things at the Froghouse. Brimer gave in and let Dane start a mail-order website for a couple of years, but he kept the inventory separate. It fizzled out when the server crashed and they had problems with code and couldn’t find any willing computer guys to fix it. They dropped the domain. Brimer never got excited about the venture, and Dane moved on to work at a surf company managing online sales.

“I remember when I was younger, I thought, ‘I can run this place,'” Beho confides during a private conversation, away from Brimer’s ears. The 61-year-old remains a mainstay despite having a bachelor’s degree in elementary education and even though, as Brimer admits, the job doesn’t pay well. Beho also gets fired a lot. But he has a key, so he just shows up, opens the shop and gets back to it.

“But now I know, if I owned this place for one year, we would be out of business,” he says. “The way TK manages this place is beyond comprehension. To have survived for this many years, it’s astonishing. He runs it like—there is a term for it—like chaos. But he does it.”

“I knew I wanted to be at this surf shop all my life,” Brimer says. “I never wanted to be rich. I wanted to surf and travel. I have been on too many surf trips to count, and I have surfed six out of the past seven days.”

Excellent blog here! Also your site loads up very fast! What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my site loaded up as fast as yours lol

You’ve made some good points there. I checked on the net for more info about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this website.

Magnificent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely fantastic. I really like what you have acquired here, really like what you are saying and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it sensible. I cant wait to read far more from you. This is actually a wonderful site.

I am really grateful to the owner of this web site who has shared this fantastic post at here.

My partner and I stumbled over here coming from a different page and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to exploring your web page again.

I want to to thank you for this fantastic read!! I absolutely enjoyed every little bit of it. I have got you bookmarked to look at new things you post…

Hello, i feel that i noticed you visited my weblog thus i got here to go back the want?.I am attempting to to find things to enhance my web site!I guess its good enough to make use of some of your ideas!!

What i don’t realize is in reality how you are not actually much more neatly-appreciated than you might be right now. You’re very intelligent. You recognize thus considerably when it comes to this matter, made me in my opinion believe it from numerous various angles. Its like men and women aren’t involved until it is one thing to accomplish with Girl gaga! Your personal stuffs nice. At all times deal with it up!

Thanks for the good writeup. It actually was once a entertainment account it. Look complex to more introduced agreeable from you! By the way, how can we keep in touch?

Wow, fantastic blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is magnificent, let alone the content!

Heya! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing a few months of hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any solutions to protect against hackers?

Howdy! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I genuinely enjoy reading your blog posts. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that cover the same topics? Many thanks!

I do not even know how I ended up right here, however I believed this post used to be great. I don’t realize who you are but certainly you’re going to a famous blogger when you are not already. Cheers!

Nice post. I was checking constantly this weblog and I’m inspired! Extremely useful info specially the ultimate part 🙂 I take care of such info a lot. I used to be seeking this certain information for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon every day. It’s always helpful to read articles from other authors and practice a little something from their websites.

Heya i am for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out much. I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

It’s going to be end of mine day, but before finish I am reading this great article to improve my knowledge.

Hi there! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having problems finding one? Thanks a lot!

Amazing blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your design. Thanks

Excellent blog! Do you have any tips and hints for aspiring writers? I’m hoping to start my own website soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you recommend starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many choices out there that I’m totally confused .. Any suggestions? Kudos!

Hi there, yeah this piece of writing is in fact fastidious and I have learned lot of things from it regarding blogging. thanks.

Genuinely when someone doesn’t know then its up to other people that they will assist, so here it happens.

Right away I am going to do my breakfast, later than having my breakfast coming again to read other news.

This web site certainly has all the information I wanted about this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

This site was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something that helped me. Cheers!

I’ve been browsing online more than 2 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me. Personally, if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the internet will be much more useful than ever before.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back in the future. All the best

I don’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but definitely you’re going to a famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

I’m amazed, I have to admit. Seldom do I come across a blog that’s both equally educative and amusing, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is an issue that too few folks are speaking intelligently about. I’m very happy I found this during my hunt for something regarding this.

all the time i used to read smaller articles which also clear their motive, and that is also happening with this post which I am reading at this place.

My spouse and I stumbled over here from a different page and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so i am just following you. Look forward to looking over your web page for a second time.

excellent publish, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t understand this. You should proceed your writing. I am sure, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll be grateful if you continue this in future. Many people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Wow, wonderful weblog layout! How long have you ever been blogging for? you make running a blog glance easy. The overall look of your website is excellent, let alone the content!

Hello colleagues, fastidious post and fastidious arguments commented here, I am really enjoying by these.

I delight in, result in I found exactly what I used to be having a look for. You’ve ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

What i don’t understood is in truth how you are not actually much more smartly-appreciated than you may be right now. You’re very intelligent. You understand thus considerably on the subject of this subject, made me personally imagine it from a lot of varied angles. Its like women and men are not interested except it’s one thing to do with Woman gaga! Your own stuffs outstanding. Always take care of it up!

You ought to take part in a contest for one of the finest websites on the web. I’m going to highly recommend this web site!

I’ve learn several excellent stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how a lot effort you put to create this type of excellent informative website.

I really like your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to find out where u got this from. many thanks

Admiring the persistence you put into your website and detailed information you provide. It’s awesome to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same out of date rehashed material. Fantastic read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

If you are going for best contents like me, just go to see this website daily because it presents feature contents, thanks

Howdy very cool site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionally? I’m glad to seek out numerous helpful information right here in the submit, we’d like develop extra techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

If some one wishes expert view regarding blogging afterward i recommend him/her to visit this website, Keep up the nice work.

Keep on working, great job!

I am really impressed with your writing talents and also with the layout in your weblog. Is that this a paid theme or did you modify it your self? Either way stay up the excellent high quality writing, it is rare to peer a nice weblog like this one these days..

For newest news you have to visit world-wide-web and on internet I found this site as a finest web site for most up-to-date updates.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a writer for your site. You have some really good articles and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an email if interested. Cheers!

Greate pieces. Keep writing such kind of information on your page. Im really impressed by your site.

Hello there, You’ve performed a great job. I’ll certainly digg it and in my view recommend to my friends. I am confident they will be benefited from this web site.

Hi! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting sick and tired of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be great if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my weblog so i came to “return the favor”.I am attempting to find things to enhance my web site!I suppose its ok to use a few of your ideas!!

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an really long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say great blog!

Outstanding quest there. What happened after? Take care!

Thanks very interesting blog!

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a bit, but instead of that, this is great blog. A great read. I’ll certainly be back.

First of all I want to say awesome blog! I had a quick question which I’d like to ask if you don’t mind. I was interested to know how you center yourself and clear your mind before writing. I have had a hard time clearing my mind in getting my ideas out. I do enjoy writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes are lost simply just trying to figure out how to begin. Any suggestions or tips? Appreciate it!

I am actually happy to read this web site posts which includes plenty of helpful facts, thanks for providing such information.

Hi there I am so happy I found your web site, I really found you by accident, while I was searching on Aol for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say thanks for a remarkable post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read it all at the moment but I have saved it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the superb work.

Thanks for finally talking about > %blog_title% < Liked it!

Can I just say what a relief to uncover an individual who truly knows what they’re discussing online. You definitely realize how to bring a problem to light and make it important. More and more people have to check this out and understand this side of your story. I was surprised that you are not more popular since you definitely have the gift.

You are so interesting! I don’t suppose I have read through anything like that before. So good to find somebody with a few unique thoughts on this topic. Seriously.. many thanks for starting this up. This web site is one thing that’s needed on the web, someone with a bit of originality!

Everything is very open with a very clear clarification of the issues. It was really informative. Your site is useful. Many thanks for sharing!

After exploring a few of the blog posts on your blog, I honestly appreciate your technique of blogging. I saved as a favorite it to my bookmark webpage list and will be checking back in the near future. Please visit my website as well and tell me what you think.

Thanks in favor of sharing such a good thought, post is pleasant, thats why i have read it fully

I was able to find good advice from your blog posts.

Nice post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very helpful info specifically the last part 🙂 I care for such info much. I was looking for this certain information for a very long time. Thank you and good luck.

Good replies in return of this question with real arguments and explaining everything about that.

I think the admin of this web page is genuinely working hard in support of his website, since here every material is quality based information.

Thanks designed for sharing such a nice thinking, piece of writing is nice, thats why i have read it entirely

Hi there, just wanted to say, I liked this blog post. It was funny. Keep on posting!

I was suggested this web site by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my trouble. You’re wonderful! Thanks!

I think that everything published was very logical. However, think about this, what if you wrote a catchier post title? I ain’t suggesting your information isn’t solid, however suppose you added a post title that grabbed folk’s attention? I mean %BLOG_TITLE% is a little boring. You might glance at Yahoo’s front page and see how they write article headlines to grab viewers to open the links. You might add a video or a picture or two to get readers excited about everything’ve written. In my opinion, it might make your posts a little bit more interesting.

Great site you have here but I was wanting to know if you knew of any community forums that cover the same topics talked about here? I’d really like to be a part of online community where I can get opinions from other experienced individuals that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Bless you!

Hey would you mind stating which blog platform you’re working with? I’m going to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a difficult time choosing between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S Apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask!

Hi there it’s me, I am also visiting this website regularly, this website is genuinely nice and the users are really sharing good thoughts.

I really like what you guys are up too. This sort of clever work and exposure! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve included you guys to my own blogroll.

Great blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my blog jump out. Please let me know where you got your theme. Appreciate it

It’s an awesome paragraph for all the internet users; they will get advantage from it I am sure.

My developer is trying to convince me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the costs. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on a variety of websites for about a year and am worried about switching to another platform. I have heard excellent things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can transfer all my wordpress posts into it? Any kind of help would be really appreciated!

I’ve read some excellent stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you set to make this sort of fantastic informative web site.

We stumbled over here coming from a different website and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to looking into your web page for a second time.

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any suggestions?

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually something that I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and very broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

I do not know whether it’s just me or if everyone else encountering problems with your website. It appears as if some of the written text on your posts are running off the screen. Can someone else please provide feedback and let me know if this is happening to them too? This could be a problem with my browser because I’ve had this happen previously. Kudos

Do you have a spam problem on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was wondering your situation; many of us have developed some nice methods and we are looking to exchange methods with other folks, why not shoot me an e-mail if interested.

You ought to take part in a contest for one of the best sites on the net. I am going to highly recommend this site!

I visited several web sites but the audio quality for audio songs present at this web site is genuinely wonderful.

Paragraph writing is also a excitement, if you know after that you can write if not it is complicated to write.

each time i used to read smaller content that also clear their motive, and that is also happening with this post which I am reading at this time.

Link exchange is nothing else except it is only placing the other person’s webpage link on your page at appropriate place and other person will also do same in support of you.

Magnificent website. A lot of helpful info here. I am sending it to some pals ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thank you on your sweat!

I for all time emailed this blog post page to all my friends, for the reason that if like to read it next my friends will too.

Hi every one, here every person is sharing these kinds of experience, so it’s nice to read this blog, and I used to pay a quick visit this blog daily.

Hi there, its fastidious article regarding media print, we all be familiar with media is a wonderful source of facts.

Excellent goods from you, man. I’ve be aware your stuff prior to and you are just too great. I actually like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you’re saying and the way in which in which you assert it. You’re making it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it wise. I cant wait to read much more from you. This is really a great web site.

My brother suggested I might like this web site. He was totally right. This submit actually made my day. You can not consider just how much time I had spent for this info! Thank you!

Hello just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your post seem to be running off the screen in Internet explorer. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the problem resolved soon. Cheers

Great site. A lot of helpful info here. I’m sending it to a few buddies ans also sharing in delicious. And naturally, thanks for your effort!

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up and also the rest of the website is very good.

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright infringement? My website has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either authored myself or outsourced but it seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my agreement. Do you know any techniques to help stop content from being ripped off? I’d definitely appreciate it.

Wow, fantastic blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is wonderful, as well as the content!

Amazing! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a totally different subject but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

Thanks in support of sharing such a fastidious opinion, article is fastidious, thats why i have read it entirely

Its not my first time to pay a visit this website, i am visiting this web site dailly and take pleasant facts from here every day.

Excellent article! We will be linking to this great content on our website. Keep up the good writing.

My spouse and I stumbled over here from a different web address and thought I should check things out. I like what I see so i am just following you. Look forward to looking over your web page repeatedly.

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this website. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s hard to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and visual appeal. I must say you’ve done a awesome job with this. Also, the blog loads super quick for me on Internet explorer. Superb Blog!

Touche. Sound arguments. Keep up the great spirit.

If you desire to get a good deal from this post then you have to apply such strategies to your won webpage.

Thanks for sharing such a pleasant opinion, piece of writing is good, thats why i have read it entirely

I truly love your site.. Excellent colors & theme. Did you develop this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m planning to create my own site and want to know where you got this from or exactly what the theme is called. Cheers!

Hey There. I found your blog the usage of msn. This is a really well written article. I will make sure to bookmark it and come back to learn more of your helpful info. Thank you for the post. I will certainly comeback.

Hi i am kavin, its my first occasion to commenting anywhere, when i read this paragraph i thought i could also create comment due to this sensible post.

Hi! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please share. Kudos!

I have to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writing this site. I really hope to check out the same high-grade blog posts by you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my very own website now 😉

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good gains. If you know of any please share. Kudos!

I was suggested this blog by way of my cousin. I am no longer positive whether this post is written via him as no one else realize such particular about my difficulty. You are amazing! Thank you!

Fastidious response in return of this difficulty with firm arguments and telling all concerning that.

Inspiring story there. What happened after? Good luck!

Paragraph writing is also a excitement, if you know after that you can write otherwise it is complex to write.

Its not my first time to pay a visit this web site, i am visiting this website dailly and take pleasant data from here every day.

Hey there, I think your website might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your blog site in Opera, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about %meta_keyword%. Regards

Hello! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing several weeks of hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any methods to prevent hackers?

Hi there would you mind letting me know which webhost you’re using? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different internet browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you recommend a good web hosting provider at a reasonable price? Kudos, I appreciate it!

It’s amazing in support of me to have a web site, which is valuable for my know-how. thanks admin

This piece of writing is really a fastidious one it assists new net users, who are wishing for blogging.

I visited various blogs except the audio quality for audio songs present at this web page is in fact marvelous.

I was able to find good info from your blog articles.

Every weekend i used to pay a visit this site, as i want enjoyment, since this this website conations really nice funny information too.

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Many thanks, However I am going through troubles with your RSS. I don’t know why I cannot subscribe to it. Is there anyone else having the same RSS problems? Anyone that knows the answer will you kindly respond? Thanks!!

Spot on with this write-up, I absolutely feel this amazing site needs a great deal more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read through more, thanks for the information!

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your wonderful post. Also, I have shared your website in my social networks!

What’s Going down i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It absolutely useful and it has aided me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & help other users like its helped me. Great job.

Nice answers in return of this matter with solid arguments and telling the whole thing regarding that.

Whoa! This blog looks just like my old one! It’s on a totally different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Excellent choice of colors!

Somebody necessarily help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the first time I frequented your website page and up to now? I amazed with the analysis you made to create this actual submit incredible. Excellent task!

Good post. I am dealing with some of these issues as well..

This website was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something which helped me. Appreciate it!

Hello Dear, are you in fact visiting this site regularly, if so after that you will without doubt take fastidious knowledge.

Ahaa, its nice dialogue about this post at this place at this webpage, I have read all that, so now me also commenting at this place.

Hi there, yeah this post is actually nice and I have learned lot of things from it about blogging. thanks.

Do you have a spam problem on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was curious about your situation; we have created some nice procedures and we are looking to trade techniques with other folks, please shoot me an email if interested.

I just like the valuable information you supply for your articles. I will bookmark your blog and take a look at again right here regularly. I’m relatively certain I’ll be informed many new stuff proper right here! Best of luck for the following!

What a information of un-ambiguity and preserveness of precious familiarity concerning unexpected emotions.

It’s remarkable to pay a quick visit this web page and reading the views of all colleagues about this piece of writing, while I am also zealous of getting familiarity.

My spouse and I stumbled over here by a different web address and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you. Look forward to going over your web page again.

Wow, amazing blog structure! How long have you ever been running a blog for? you made blogging glance easy. The total look of your web site is great, let alone the content material!

Hello there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

you are really a just right webmaster. The website loading pace is incredible. It seems that you’re doing any distinctive trick. Also, The contents are masterpiece. you have done a wonderful activity on this subject!

Remarkable! Its truly amazing piece of writing, I have got much clear idea about from this piece of writing.

I just like the helpful information you supply for your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and take a look at once more here regularly. I am somewhat sure I will be told many new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

I really love your blog.. Great colors & theme. Did you develop this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m planning to create my own blog and want to find out where you got this from or exactly what the theme is named. Cheers!

Hi friends, how is everything, and what you wish for to say on the topic of this paragraph, in my view its truly remarkable in support of me.

whoah this weblog is great i really like reading your posts. Keep up the great work! You know, lots of persons are looking round for this information, you can aid them greatly.

At this time I am ready to do my breakfast, after having my breakfast coming yet again to read additional news.

Link exchange is nothing else however it is simply placing the other person’s web site link on your page at proper place and other person will also do same in support of you.

Excellent article. I will be facing a few of these issues as well..

Since the admin of this web page is working, no question very shortly it will be renowned, due to its quality contents.

Excellent blog right here! Additionally your website lots up very fast! What web host are you using? Can I am getting your associate hyperlink to your host? I want my site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Useful information. Fortunate me I found your website accidentally, and I’m surprised why this twist of fate did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

These are really fantastic ideas in on the topic of blogging. You have touched some good things here. Any way keep up wrinting.

Thank you for sharing your info. I truly appreciate your efforts and I am waiting for your next post thanks once again.

Hello I am so happy I found your web site, I really found you by mistake, while I was searching on Aol for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a fantastic post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read it all at the moment but I have saved it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a lot more, Please do keep up the fantastic jo.

wonderful issues altogether, you just gained a logo reader. What would you recommend about your publish that you made a few days ago? Any sure?

Amazing! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a completely different subject but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Excellent choice of colors!

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have truly enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again soon!

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly.

Excellent weblog right here! Additionally your web site rather a lot up fast! What web host are you using? Can I am getting your associate hyperlink in your host? I desire my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

These are genuinely impressive ideas in regarding blogging. You have touched some fastidious points here. Any way keep up wrinting.

Can you tell us more about this? I’d want to find out more details.

Today, while I was at work, my cousin stole my apple ipad and tested to see if it can survive a 25 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It will always be interesting to read content from other authors and practice something from their web sites.

It’s hard to come by knowledgeable people on this subject, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

This is my first time visit at here and i am really happy to read everthing at alone place.

Remarkable! Its in fact amazing post, I have got much clear idea about from this article.

Hello colleagues, how is the whole thing, and what you wish for to say concerning this piece of writing, in my view its in fact awesome for me.

Yesterday, while I was at work, my sister stole my apple ipad and tested to see if it can survive a thirty foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

I could not resist commenting. Very well written!

Your style is so unique compared to other folks I have read stuff from. Thanks for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just bookmark this page.

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Thanks

It’s going to be end of mine day, however before finish I am reading this enormous paragraph to increase my knowledge.

Thanks in support of sharing such a fastidious thought, post is good, thats why i have read it fully

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Many thanks, However I am going through troubles with your RSS. I don’t know the reason why I cannot join it. Is there anybody else getting the same RSS problems? Anyone who knows the answer will you kindly respond? Thanx!!

I blog quite often and I seriously appreciate your information. This great article has truly peaked my interest. I’m going to book mark your blog and keep checking for new details about once per week. I opted in for your Feed as well.

I relish, result in I discovered just what I was taking a look for. You’ve ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

Hi there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.

Link exchange is nothing else except it is simply placing the other person’s website link on your page at suitable place and other person will also do same for you.

Hi, I log on to your blog daily. Your story-telling style is awesome, keep up the good work!

Heya! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the superb work!

Hola! I’ve been following your weblog for some time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Dallas Tx! Just wanted to tell you keep up the excellent job!

Saved as a favorite, I love your web site!

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your blog? My website is in the exact same niche as yours and my users would definitely benefit from a lot of the information you present here. Please let me know if this alright with you. Thanks a lot!

Nice blog here! Also your web site loads up fast! What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

Greetings I am so grateful I found your weblog, I really found you by error, while I was searching on Bing for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a tremendous post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read it all at the minute but I have saved it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the fantastic jo.

Great blog! Do you have any recommendations for aspiring writers? I’m hoping to start my own website soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you advise starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many choices out there that I’m totally overwhelmed .. Any suggestions? Thanks!

Because the admin of this site is working, no question very rapidly it will be well-known, due to its quality contents.

Ahaa, its pleasant discussion on the topic of this paragraph at this place at this weblog, I have read all that, so at this time me also commenting here.

Great article! We are linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the great writing.

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I have joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your great post. Also, I have shared your site in my social networks!

Fantastic beat ! I would like to apprentice even as you amend your web site, how could i subscribe for a weblog website? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I have been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear idea

Hello my family member! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and include almost all important infos. I would like to look extra posts like this .

What’s up Dear, are you truly visiting this site daily, if so afterward you will absolutely obtain fastidious know-how.

Good way of describing, and fastidious article to obtain data about my presentation topic, which i am going to deliver in academy.

Hi there friends, how is all, and what you would like to say regarding this piece of writing, in my view its actually awesome for me.

I am genuinely grateful to the owner of this site who has shared this fantastic piece of writing at at this place.

Excellent post. I absolutely appreciate this site. Keep writing!

I believe this is among the so much important info for me. And i’m glad studying your article. However should commentary on some general issues, The site style is ideal, the articles is truly great : D. Excellent task, cheers

You are so interesting! I do not suppose I’ve truly read through anything like that before. So great to find someone with a few original thoughts on this subject. Really.. thank you for starting this up. This site is something that’s needed on the internet, someone with a bit of originality!

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d most certainly donate to this fantastic blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to fresh updates and will talk about this site with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

I’m now not positive the place you are getting your info, however great topic. I needs to spend a while studying more or working out more. Thanks for excellent info I used to be on the lookout for this info for my mission.

Hi there I am so thrilled I found your webpage, I really found you by mistake, while I was researching on Aol for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say cheers for a fantastic post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to go through it all at the minute but I have saved it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the awesome job.

Highly descriptive post, I enjoyed that bit. Will there be a part 2?

fantastic points altogether, you just gained emblem reader. What would you suggest in regards to your post that you made a few days ago? Any certain?

An impressive share! I have just forwarded this onto a coworker who has been doing a little research on this. And he actually bought me dinner because I found it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending the time to talk about this topic here on your blog.

Great weblog right here! Also your website rather a lot up very fast! What web host are you the usage of? Can I am getting your affiliate link in your host? I want my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Hello to all, how is everything, I think every one is getting more from this web site, and your views are nice in support of new visitors.

Hi there to all, the contents existing at this web site are genuinely awesome for people knowledge, well, keep up the nice work fellows.

Greetings from California! I’m bored to tears at work so I decided to check out your site on my iphone during lunch break. I really like the information you provide here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home. I’m shocked at how quick your blog loaded on my cell phone .. I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, excellent blog!

What’s up, this weekend is nice for me, since this occasion i am reading this wonderful informative article here at my house.

This design is spectacular! You most certainly know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Wonderful job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

Hello there! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and tell you I truly enjoy reading through your blog posts. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same topics? Many thanks!

Hi i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anyplace, when i read this post i thought i could also make comment due to this sensible piece of writing.

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do some research about this. We got a grab a book from our area library but I think I learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such fantastic info being shared freely out there.

We are a gaggle of volunteers and starting a brand new scheme in our community. Your website provided us with valuable information to work on. You have done an impressive job and our entire group will likely be thankful to you.

What a stuff of un-ambiguity and preserveness of valuable experience on the topic of unexpected emotions.

Incredible! This blog looks just like my old one! It’s on a completely different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

That is very fascinating, You’re an overly professional blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to in the hunt for more of your fantastic post. Also, I have shared your web site in my social networks

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my site thus i got here to return the choose?.I’m trying to find issues to enhance my site!I assume its adequate to make use of some of your ideas!!

Thanks for the good writeup. It in reality was once a amusement account it. Glance complex to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we keep in touch?

It’s very trouble-free to find out any matter on net as compared to textbooks, as I found this article at this website.

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your blog and check again here regularly. I’m quite certain I will learn many new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

What i don’t understood is if truth be told how you’re no longer actually much more smartly-liked than you might be now. You are so intelligent. You already know thus significantly in terms of this matter, produced me personally imagine it from so many varied angles. Its like women and men are not interested except it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your individual stuffs great. All the time deal with it up!

Thanks for the auspicious writeup. It in reality was once a enjoyment account it. Look complicated to more delivered agreeable from you! By the way, how could we be in contact?

I’ve been browsing online more than three hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will be a lot more useful than ever before.

Terrific work! That is the type of information that should be shared around the net. Disgrace on Google for not positioning this put up higher! Come on over and visit my website . Thank you =)

Hi would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re working with? I’m looking to start my own blog soon but I’m having a hard time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something completely unique. P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

I have been surfing online more than 3 hours today, yet I never found any attention-grabbing article like yours. It is pretty price sufficient for me. In my opinion, if all site owners and bloggers made good content material as you did, the net will likely be much more useful than ever before.

Excellent post. I was checking constantly this blog and I’m impressed! Very useful information specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this certain info for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

Currently it seems like BlogEngine is the top blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you’re using on your blog?

I could not resist commenting. Very well written!

I used to be able to find good info from your articles.

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you actually understand what you’re speaking approximately! Bookmarked. Please also talk over with my web site =). We may have a hyperlink change contract among us

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular article! It’s the little changes that make the biggest changes. Many thanks for sharing!

I am in fact happy to read this webpage posts which carries lots of valuable data, thanks for providing such information.

I am extremely inspired along with your writing abilities and also with the structure to your blog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you modify it your self? Anyway stay up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a great blog like this one these days..

Hi! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m absolutely enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Valuable information. Fortunate me I discovered your site by chance, and I’m shocked why this twist of fate did not took place in advance! I bookmarked it.

Asking questions are actually pleasant thing if you are not understanding something totally, however this paragraph presents good understanding even.

Hi there, this weekend is pleasant in support of me, for the reason that this point in time i am reading this impressive educational article here at my residence.

Hello Dear, are you actually visiting this website on a regular basis, if so then you will definitely take nice experience.

Hello mates, how is the whole thing, and what you would like to say regarding this post, in my view its really awesome in support of me.

There’s definately a great deal to know about this subject. I like all the points you have made.

A motivating discussion is definitely worth comment. I believe that you ought to publish more about this subject matter, it may not be a taboo subject but usually people do not discuss these subjects. To the next! Many thanks!!

Thanks for finally talking about > %blog_title% < Liked it!

It is in point of fact a great and helpful piece of information. I’m satisfied that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Hello! I understand this is sort of off-topic but I needed to ask. Does running a well-established website like yours take a massive amount work? I am completely new to operating a blog but I do write in my diary everyday. I’d like to start a blog so I will be able to share my own experience and feelings online. Please let me know if you have any recommendations or tips for new aspiring bloggers. Thankyou!

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my site so i came to “return the favor”.I am attempting to find things to improve my web site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

Have you ever considered creating an e-book or guest authoring on other sites? I have a blog based on the same ideas you discuss and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I know my audience would value your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an email.

I’m no longer sure the place you’re getting your info, however good topic. I needs to spend a while studying much more or understanding more. Thank you for excellent info I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

I want to to thank you for this excellent read!! I absolutely loved every little bit of it. I have got you saved as a favorite to look at new stuff you post…

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful info. Thanks for the post. I’ll definitely comeback.

Greetings! Very helpful advice within this post! It’s the little changes that produce the greatest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

I’d like to find out more? I’d care to find out more details.

Hey there, I think your website might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Opera, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, terrific blog!

I always used to read article in news papers but now as I am a user of internet so from now I am using net for articles or reviews, thanks to web.

I got this website from my buddy who informed me on the topic of this web page and now this time I am browsing this site and reading very informative articles or reviews here.

Unquestionably believe that that you said. Your favorite reason seemed to be at the internet the easiest thing to be mindful of. I say to you, I definitely get annoyed at the same time as other folks think about concerns that they just do not recognize about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the entire thing with no need side-effects , people can take a signal. Will probably be again to get more. Thanks

Hello there! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could locate a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I do believe that you should publish more about this issue, it might not be a taboo subject but typically folks don’t discuss such subjects. To the next! Cheers!!

Everyone loves what you guys are usually up too. Such clever work and coverage! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve included you guys to my personal blogroll.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve really enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again very soon!

I’ll right away grasp your rss as I can not find your e-mail subscription hyperlink or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly let me recognise in order that I may subscribe. Thanks.

Howdy! I simply would like to offer you a big thumbs up for your excellent info you have right here on this post. I’ll be returning to your blog for more soon.

An interesting discussion is definitely worth comment. I do think that you ought to publish more on this subject, it might not be a taboo subject but usually people do not discuss such subjects. To the next! Many thanks!!

Hey would you mind stating which blog platform you’re using? I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m having a hard time choosing between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique. P.S Apologies for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please share. Thanks!

Everyone loves it when people get together and share thoughts. Great site, keep it up!

Someone essentially lend a hand to make significantly articles I’d state. That is the very first time I frequented your website page and to this point? I amazed with the research you made to create this particular publish extraordinary. Magnificent process!

As the admin of this web site is working, no hesitation very shortly it will be famous, due to its quality contents.

My brother recommended I would possibly like this website. He was once entirely right. This publish actually made my day. You cann’t imagine simply how so much time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

Attractive section of content. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to say that I get in fact loved account your weblog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing on your feeds or even I achievement you get admission to constantly rapidly.

Hi there, I read your blogs daily. Your writing style is awesome, keep it up!

Hurrah, that’s what I was searching for, what a data! existing here at this webpage, thanks admin of this web page.

I was recommended this blog by means of my cousin. I’m not sure whether or not this publish is written by means of him as no one else recognize such certain about my trouble. You’re amazing! Thanks!

Keep this going please, great job!

When someone writes an paragraph he/she retains the image of a user in his/her mind that how a user can know it. So that’s why this post is great. Thanks!

Hi Dear, are you in fact visiting this web page daily, if so afterward you will absolutely obtain pleasant know-how.

I’ll right away grab your rss as I can’t to find your e-mail subscription link or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me recognize in order that I could subscribe. Thanks.

I pay a visit day-to-day a few web sites and websites to read articles or reviews, but this weblog provides feature based posts.

This website really has all the information I wanted about this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

Ahaa, its pleasant conversation about this article here at this website, I have read all that, so at this time me also commenting at this place.

Very energetic post, I liked that a lot. Will there be a part 2?

Keep this going please, great job!

This is my first time pay a quick visit at here and i am genuinely impressed to read everthing at one place.

I know this site offers quality based articles or reviews and other material, is there any other site which gives these information in quality?

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again soon!

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back frequently!

Good way of telling, and pleasant paragraph to take information about my presentation subject matter, which i am going to deliver in university.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you helped me.

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and check again here regularly. I am quite sure I’ll learn plenty of new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Have you ever considered about including a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is valuable and everything. However think of if you added some great visuals or video clips to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with images and videos, this blog could undeniably be one of the greatest in its field. Wonderful blog!

I have been surfing online more than 2 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will be a lot more useful than ever before.

Very good write-up. I definitely appreciate this site. Thanks!

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and extremely broad for me. I’m looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

Keep on writing, great job!

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative. I am going to watch out for brussels. I’ll be grateful if you continue this in future. A lot of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Wow, that’s what I was exploring for, what a stuff! present here at this webpage, thanks admin of this web site.

Link exchange is nothing else except it is just placing the other person’s blog link on your page at appropriate place and other person will also do similar in favor of you.

It’s very trouble-free to find out any topic on net as compared to textbooks, as I found this post at this website.

I’m amazed, I have to admit. Rarely do I encounter a blog that’s equally educative and engaging, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something which not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I’m very happy that I stumbled across this during my hunt for something regarding this.

wonderful publish, very informative. I wonder why the other experts of this sector don’t notice this. You must continue your writing. I am sure, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

Good info. Lucky me I discovered your website by chance (stumbleupon). I’ve book-marked it for later!

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say superb blog!

I want to to thank you for this great read!! I certainly enjoyed every bit of it. I’ve got you saved as a favorite to look at new stuff you post…

I am regular visitor, how are you everybody? This paragraph posted at this website is in fact good.

Quality articles is the crucial to be a focus for the viewers to go to see the site, that’s what this site is providing.

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your blog. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Exceptional work!

Nice blog here! Also your web site loads up fast! What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

You actually make it seem really easy along with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually one thing that I think I’d by no means understand. It sort of feels too complicated and extremely wide for me. I’m looking forward on your subsequent submit, I’ll attempt to get the hang of it!

Hi! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this website? I’m getting sick and tired of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

I relish, cause I discovered just what I used to be taking a look for. You’ve ended my four day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your site when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

It’s an remarkable piece of writing in support of all the web viewers; they will take advantage from it I am sure.