That Orange County had two Ku Klux Klan klaverns in the 1920’s is a tale well-told. Orange County district attorney Alexander P. Nelson helped beat back both local Klan chapters ( “klaverns” in Klan speak) with the help of membership lists he came to possess; they proved to be the klantidote against the Hooded Order’s attempts to take over early civic life. But early scholars of the OC Klan had a difficult time trying to replicate Nelson’s feat, as finding copies of both lists proved elusive.

The question of how many original Klukkers didn’t get intimidated by Nelson’s Klan busting ways in 1922 and helped build the ranks of the second OC klavern, which boasted more than 1,000 members, just a few months afterward loomed as an academic curiosity–until now.

A tormenting fact of fact-finding life, historians can scour the ends of the earth, only to later find out the reveals they sought were closer than they thought. That was the case for Christopher Cocoltchos, whose 1979 UCLA dissertation The Invisible Government and the Viable Community: The Ku Klux Klan in Orange County, California During the 1920’s, is enjoying a revival in popularity thanks to a high-profile fight to nix William E. Fanning’s name from an elementary school in Brea because he was Klan.

Cocoltchos tried his damnedest to find the first klavern list, searching LA and OC county archives for it, only to come up empty. The backstory of the roster is infamous; the Los Angeles Klan led an April 22, 1922 raid on an Inglewood household suspected of bootlegging. Police arrived on scene and a shoot out ensued, leaving one Klansman dead and two others injured, all klukkers who also happened to be LA law enforcement. LA County DA Thomas L. Woolwine responded by raiding the headquarters of the LA Klan, taking membership materials as yield.

“Woolwine Gives Nelson Complete List of All Members in County” read an Orange Daily News headline a week after the raid. Articles that followed alluded to the rosters’ contents: roughly 200 members, mostly with Santa Ana addresses. Nelson didn’t reveal the list in full, but wielded it against Arthur E. Koepsel, Chairman of the Orange County Republican Party Central Committee and would-be DA challenger. Despite Koepsel’s denials, Nelson provided the Santa Ana attorney’s membership application date to the press while outing him as having been a provisional Exalted Cyclops.

OC’s first klavern never fully recovered and fell apart in a matter of mere months.

If found, Cocoltchos could’ve compared the membership list with that of the klavern later led by Exalted Cyclops Reverend Leon Myers of the First Christian Church in Anaheim. But he couldn’t. “There’s no way of knowing which people belonged to the pre-Myers Klan, and, consequently, if there was any membership overlap…between the pre-Myers and Myers led Klans,” Cocoltchos wrote in a footnote.

Cocoltchos continued researching the Klan at the Mother Colony History Room of the Anaheim Public Library during the 1970’s with the help of late librarian Opal Kissinger. “All available evidence reveals little, if any, membership overlap between the two klaverns,” he wrote, shorting of having both lists. Unbeknownst to him, OC historian Leo J. Friis donated copies of two Klan lists to the library in 1972, only they remained under a five-year seal that expired in August 1977, two years before Cocoltchos finished his dissertation.

The lists and their whereabouts led to Klan confusion in early scholarship. Karol Keith Richards’ 1968 study The Ku Klux Klan in Orange County, 1922-1925 claimed evidence of La Habra Klan membership was inconclusive–a sure sign he didn’t have the lists at his scholarly disposal. Published in 1992, no such excuse is afforded to Esther Cramer’s Brea: The City of Oil, Oranges and Opportunity, a city commissioned history which cited only the first, smaller klavern’s existence in stating that there were “no records” to indicate Klan activity in Brea!

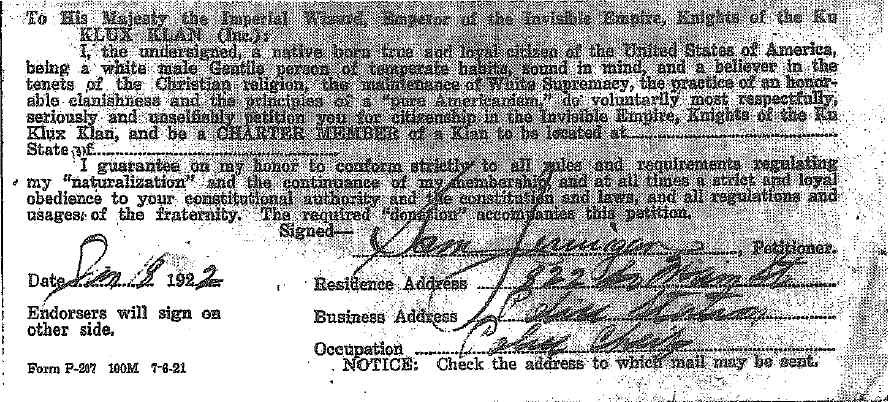

As reported last week, the Library of Congress believes the Friis membership list of the second Klan to be similar to or a derivative of the list it housed in its collection until 1982, before it became the only missing item from a manuscript collection donated in 1954 by Earnest Ganahl, an Anaheim anti-Klan activist. Nobody really bothers questioning the Friis list of the first Klan. It’s titled as a membership list and holds exactly 200 names, most with Santa Ana addresses. In the Fanning fight, Brea Olinda Unified School District trustee Paul Ruiz, a Cypress police detective by day, even went as far as to claim that Friis only donated the first, shorter list in an attempt to discredit the second, longer one where Fanning is named.

Absurdities aside, the question of how many Klansmen from the first klavern joined the second one can be examined with both lists, even if the latter is missing some names (Louis Plummer of Fullerton Plummer Auditorium fame, where are you?). After careful review by the Weekly, a little more than 10 percent of Klansmen, 23 in total, on the first list appear on the second. They include James Henry Whitaker, Buena Park’s first postmaster who later took up the job in Anaheim around 1923–and held the position until 1936 long after Anaheimers recalled four Klan councilmen in February 1925. Whitaker’s address is exactly the same on both Friis lists.

Other notable krossover Klukkers include George W. Cullen, a clerk for Brea Olinda High in 1926 and Clyde Williams, one of several Klansmen Nelson outed as part of Klan dominated slates seeking to take over both the Democratic and Republican Party Central Committees; Anaheim’s anti-Klan activists, aware of Nelson’s reputation, gave him a partial copy of the membership list they assembled from material bought from a King Kleagle on the take.

Perhaps the most infamous dual membership Klansman is Emory Knipe. He belonged to the so-called “Big Four” of Anaheim Kouncilmen who took power in 1924 before getting recalled nine months later. Aside from Knipe and the gang, the other revealing take away from cross-referencing OC Klan membership is that most of the Klukkers who stuck around for the second klavern had Anaheim addresses by the time they appeared on Friis’ lists again. The city, of course, proved to be ground zero for the second coming of the OC Klan.

But hey: that’s all just koincidental, right?

Gabriel San Román is from Anacrime. He’s a journalist, subversive historian and the tallest Mexican in OC. He also once stood falsely accused of writing articles on Turkish politics in exchange for free food from DönerG’s!

The KKK even controls the way we perceive things , The great city that is Santa Ana with a white majority was the the klans dream home away from home . As soon as the term ” White Flight” is coined ,the same great city, is now referded to as a impoverished barrio . It’s repeated so many times, it is now perceived as such , Now any place that has a low Anglo population is called a what ? Ghetto? Barrio? Slum? All KKK rhetoric . That really is the Klans legacy , the Confederate poison they brought with them and the seeds of division are still as strong as ever . Hidden Empire , cloaked in the dark , crosses burning , blacks and Mexicans lynchings is how they pumped fear . Now the use the system to do their dirty work , and the police think they are just doing their job ,real heros.