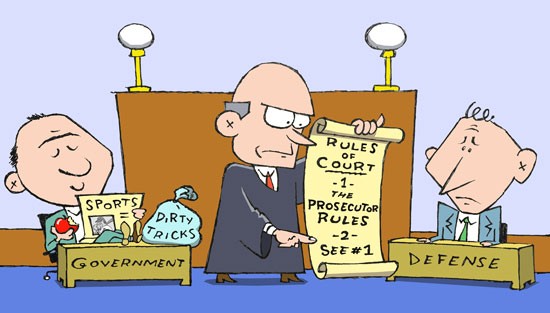

During 23 months of the ongoing Orange County snitch scandal that today won a national call for a U.S. Department of Justice probe, we’ve learned how certain courthouse prosecution teams cheat, how law-enforcement officials concoct clever explanations about how they accidentally rigged cases against dozens of defendants, and how judges–the people obligated to ensure honestly won convictions–are tolerating, if not outright encouraging, a pro-government warping of the criminal-justice system.

Our reporting has focused on a myriad of state court abuses that have captured national attention. But there’s also cause for concern inside the Ronald Reagan Federal Courthouse in Santa Ana. One sensational, pending appellate case underscores how defendants can be robbed of key evidence while FBI agents, assistant United States attorneys and judges shrug their shoulders.

Vo Duong Tran of Louisiana and Yu Sung Park of Illinois are serving 30-year sentences for 2009 convictions stemming from a bizarre home-invasion robbery plot in Orange County. Bizarre not just because the conspiracy involved a machine gun, silencers, bulletproof vests, the threat of wiping out any early arriving cops, and the expected plundering of cash and cocaine from inside a Fountain Valley residence near Mile Square Park–but also because Tran and Park are former lawmen.

Through hundreds of hours of surreptitious recordings and various other surveillance tactics, prosecutors compiled evidence of guilt. And a jury has also spoken. But the case is notable because of a post-conviction discovery. Prosecutors hid from jurors the FBI’s sweetheart–eyebrow-raising, really–deal with a Southern California underworld figure used to nab the duo. That omission wasn’t inconsequential, according to the defense. The concealment struck at the heart of their claim that the agency conducted an unseemly vendetta against Tran.

Once an 11-year-old South Vietnam boat refugee fleeing communism with his family in 1978, Tran grew up in Connecticut. By 1992, he worked as an FBI special agent in Chicago. Nearly a decade later, his tenure fell into turmoil. Agency management revoked his top-secret security clearance and, believing he was a criminal, terminated him on April Fool’s Day 2003. Tran believes the FBI acts constituted discrimination.

There is proof fellow agents loathed him. According to court records, they raided Tran’s home without a warrant to search for compromising records; and then saw a budding criminal case against him collapse. In February 2006, federal Judge Linda T. Walker declared the raid illegal and, thus, banned the fruit of the search from court. Walker also blasted two FBI agents for telling “inconsistencies” about their pursuit of Tran, whom she found “more credible.”

The fired agent moved to New Orleans and became the accomplished owner of multiple Verizon Wireless stores. Tran’s earnings topped $800,000 in 2007, according to his

income-tax return. With his girlfriend, he became a family man with two young kids.

But the FBI remained determined to bring him down. For more than a year, they conducted wiretaps and monitored his activities without success. Then, with the help of the Fountain Valley Police Department, special agents in Orange County found an informant identified in court records as Trung “Alex” Dao. A financial adviser by day and Vietnamese gangster/con artist by night, Dao worked as an around-the-clock government snitch deeply tied to Asian gangs.

With the encouragement of the FBI, Dao attempted to involve Tran in criminal enterprises, including identity theft, extortion and narcotics sales. The scheming failed before agents found the scam that finally landed their suspect in handcuffs: the home-invasion robbery plan.

The FBI located a vacant house and let Dao sell Tran on the notion of hitting the property because it belonged to a cocaine dealer who had at least $50,000 cash and wouldn’t complain to authorities. The secret government agent constructed the case by supplying the theoretical crime. He also lobbied Tran to use his friend, Park, for backup, a move aimed to satisfy future conspiracy charges, and had them both fly in from out of state, making the imaginary robbery an interstate crime, too.

Tran says he played along with Dao’s robbery idea in hopes of getting him arrested, becoming a hero and returning to law enforcement–even to the FBI. His lawyers described his damning recorded statements as “puffing . . . to gain Dao’s trust.” That story seems weak or, at least, the musings of a knucklehead. Outside of Hollywood flicks, where do such events happen?

Nevertheless, the FBI had Tran and Park where they wanted them when the pair flew into Los Angeles International Airport and arrived at a Ramada Inn in Fountain Valley. A law-enforcement technical team monitored telephone activities. Overhead and out of sound range, a helicopter hovered. More than 100 officers, including a massive SWAT team, pounced. After winning convictions, Assistant United States Attorney Robert Keenan told reporters he’d removed “dangerous people” from society.

Tran continues to insist he is the victim of an unethical FBI conspiracy that wasn’t going to end until it found an excuse for an arrest. There’s no doubt the agency invested heavily into winning. They leased a Little Saigon-area condominium for Dao, paid the informant’s restaurant and bar tabs, and reimbursed him for airfares and stays at the Bellagio Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. They even named their work “Operation Blue Dagger” and gave their husky target a cuisine code name: “BLT.”

But government officials wanted the jury relatively clueless about how badly they craved a victory over Tran. Keenan partly shielded his case from a defense onslaught against Dao, a convicted felon, by keeping him off the witness stand. Arguably more important, defense lawyers now claim the government violated the U.S. Constitution’s Brady requirement that prosecution teams surrender before trial evidence that is exculpatory for a defendant or impeaches a government witness.

Indeed, they misled the jury about the financial resources employed in the case. An FBI agent testified Dao received $45,000 for his services. In reality, the agency agreed to give him $500,000, plus another $94,000 in expenses for about six months of undercover work, according to court records.

The only reason we know the terms is because a year after the trial, Dao filed a claim against the agency, disclosed the contract, demanded payment, blasted Keenan for risking his life by naming him in court and demanded entry into the federal witness relocation program (WITSEC).

Defense lawyers say the secrecy sabotaged a valid argument that the FBI’s conduct had, at a minimum, been suspicious. Their appeals to U.S. District Court Judge Andrew J. Guilford are instructive about how the system favors prosecutors. At the time of the trial, the withholding of Dao’s lucrative contract could have been declared a Brady breach, but prosecutors know they enjoy an advantage that almost always renders their sneaky strategy moot at the appeal stage. That’s when a judge must apply a nearly impossible standard–one demanding legislative reform: Was the government’s deceit “so serious that there is a reasonable probability that the suppressed evidence would have produced a different verdict”?

Applying that criteria on Oct. 16, Guilford labeled evidence of guilt “abundant” and dismissed Park’s motion to set aside the verdict. The 42-year-old inmate will continue living in a Minnesota penitentiary. The judge is giving Tran, 48 and residing inside a New Jersey prison, more time to argue. Barring judicial relief, the men are scheduled to be freed in 2034.

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.