Will Swaim is the founding editor of OC Weekly and currently vice president of journalism for the Franklin Center for Government & Public Integrity. Call him Guillermo.

So these two frantic, bewhiskered woodsmen hack their way out the back window of the snowbound cabin in which they've been trapped for days—stuck inside this little hut as if the frozen center of a novelty-cocktail ice cube—and the older one says to the younger, “Follow the path.”

The kid's head swivels 180 degrees in two directions: nothing but hip-high, trackless snow. He turns to his elder and says, “What path?”

The old guy says, “Start walking, turn around in 10 feet and look back. You'll see it.”

CLICK HERE FOR OUR FULL 20TH ANNIVERSARY PACKAGE.

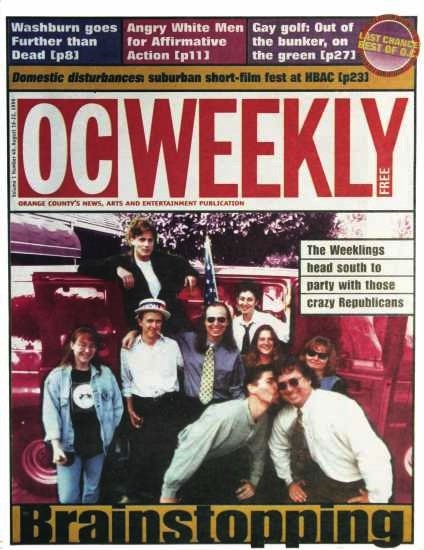

The Weekly's path forward wasn't obvious in June 1995, but looking back, I see it clearly: I used the entire operation—including a remarkable group of people in the newsroom, art department, advertising sales, circulation, human resources, finance, marketing and reception; people in Costa Mesa, at the LA Weekly and at New York's Village Voice—used all these people, without thieving, I hope, but for 11 and a half years, to work out my own DNA-level anxieties about what sociologists, psychologists, historians and your average well-educated spiritual advisers sometimes call the problem of “placelessness.”

I imagine it's easier to live in a place more obviously/conventionally compelling, a place easier to love because it has been loved so publicly for so long—New York City, maybe, or Paris. I was raised in little-loved, remote, anti-historical South Orange County. Remember the scene in Anchorman in which Will Ferrell's character confidently explains that “San Diego” is German for “a whale's vagina”? Like that, my town's developer, a division of cigarette-maker Philip Morris, attempted to appropriate the gravity—the sense of place—of a centuries-old Spanish settlement for its off-the-shelf city by calling it “Mission Viejo.” It's a Spanglish name that can't even get its gender straight (the Spanish would've been “Misión Vieja,” the English just “Old Mission”), as well as intentionally confusing the new town (circa 1966) with adobe buildings first raised two centuries before in San Juan Capistrano, 9 miles south. Mission Viejo was a great place to grow up, with tennis, football, basketball, baseball, horseback riding and the globally dominant Nadadores swim program—all of it so outrageously healthy and physical and antithetical to Philip Morris' main source of revenue, I'm saying, that it just had to be built into the marketing plan by people with a muscular sense of irony.

That sort of linguistic/social/historical/advertised irony and confusion gave at least one boy the fantods—produced in him a kind of psychic vertigo, of non-attachment, though not in the good way Buddhists describe.

Years later, the Weekly would give me the sense that I lived in a place with a history, would give me the gift of being present to what's here.

For decades, Jesus had urged me (not directly, mind you: I'm not that kind of guy) to consider the kingdom of heaven already here among us. I ignored that. And when Ram Dass said (ibid., w/r/t Jesus) I ought to be here now, I kind of sensed (pre-Weekly) that he could not mean Orange County.

In working at the Weekly, I asked my colleagues to go deeper into Orange County, begging them (my pleas encoded in less obviously idiosyncratic demands about “mission,” “story selection,” “deadlines,” ad sales, consistency of style, word counts, etc.) to prove to me that everything around us might be a hieroglyph, a semaphore, a symbol of something deeper.

“Southern California was already being reassessed in intellectually exciting ways in the '90s,” my friend and former Weekly contributor Paul Brennan recently wrote me.

Take (LA Weekly contributor and future UC Irvine visiting professor) Mike Davis' City of Quartz (about LA, published in 1990) and Ecology of Fear (also about LA, 1998), Paul says. “For anyone interested in Southern California who wasn't a dullard or a major newspaper or California's Official Whig Historian Kevin Starr, new ways of understanding the region were opening up.”

Paul went on: “But remember the big papers' reaction to Davis—a chamber of commerce mentality still ruled the day. That's what made the Weekly so valuable. It was a new voice, and it wasn't afraid of new ideas or of offending those who were. It helped show there was a world in OC beyond chamber of commerce dreams or what appeared in the Register.”

It wasn't just the dream of the business community that lay heavy upon the land. The Weekly was still in utero when, in the summer of 1995, a few months before issue No. 1, I got a call from reporter Tom Vanderbilt of The Baffler, the radical, Chicago-based pop-culture journal edited by one of my intellectual heroes, Thomas Frank. Frank would go on to write the brilliant The Conquest of Cool and the more famous What's the Matter With Kansas?

Vanderbilt, the reporter, was writing what he might have called “What's the Matter with Orange County?” I met him at the LAB in Costa Mesa. What evolved out of that meeting was, I would come to recognize, preordained: smart people from conventionally interesting places instinctively hate Orange County. Following our meeting, Vanderbilt wrote in Issue No. 8 of The Baffler:

The county seemed to inhabit a dual world: one a gray dystopia of uncertainty and falling property values; another, the accustomed bright and buoyant showcase of affluent citizens who were forming start-up software firms in small industrial parks and shopping at Coach and Hermès. It was home to one of the country's most profitable Mercedes-Benz dealers, yet ominous talk loomed of massive cuts in bus service to help bail out the county—and just how would those nannies and gardeners from Santa Ana make the daily commute to Big Canyon Villas or Belcourt? In Orange County, such paradoxes run deep and jagged like irrigation ditches: only there did it seem to make sense that the soft-spoken and earnest editor of the new “alternative weekly,” itself housed next to those software firms in a commercially zoned office park, would meet me for lunch wearing a three-piece suit, and then drive me in his BMW to a cafe at “the Lab.” Known as the county's “anti-mall,” the former canning factory is a perfect fabricated bohemia—with rusted post-industrial debris as strategically chosen as the “environmental” music at the county's real malls—made possible through the generous cooperation of a local surf/skate-wear tycoon.

I was the guy who showed up at lunch. I was not wearing a three-piece suit—hadn't owned one since Jimmy Carter's presidency. The BMW was already old when I bought it, in such bad shape by the time of l'affair Vanderbilt that my German mechanic had summed up its defects by saying he wasn't sure it was worth fixing. The leaking gas tank bothered him most. I asked him how long I could go without repairs, given, you know, the cost. He gravely eyeballed the perforated gas tank and responded with a question: “Do you smoke?”

I note these things not to defend myself or to imply (as the puritanical Vanderbilt believed) that fine suits and luxury cars are manifestations of spiritual putrefaction. I note them to show that outsiders will see in Orange County what they expect to see. It's more compelling—far easier, more common and therefore, yes, stupid—to see the place as hypocritical. It's superficial to note what's superficial.

To love Orange County deeply requires actual labor.

The entire Baffler thing read as if there had been no evolution in pop culture's perspective on suburbs, on Orange County, on Southern California. A year after we opened, the city of Lakewood's own D.J. Waldie published the landmark Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir, in which we learn that suburban predictability is a “necessary illusion” masking something that may actually be—is, in fact—weirdly spiritual somehow, or, perhaps, it's just that even this compelling deception cannot frustrate/retard/destroy the soul unless we let it through the sheer laziness of adopting someone else's perceptions. For the aptly named Vanderbilt, Orange County was only a “theme park of a county,” and “the theme, as one tourist brochure put it, is you can have anything you want.” For Waldie, beneath the master planning “is a compass of possibilities,” and “seen from above,” it's “beautiful and terrible.”

It's easy to miss Waldie's beautiful and terrible possibilities, especially if you're a Baffler writer dropped here for a few days and reading sales brochures. But loving the place where we live is difficult, even if, like me or many of my fellow Weeklings, you grew up here.

Early on, the Weekly was rightly praised for political reporting that dug beneath what was published in the Los Angeles Times and the Orange County Register. And I'm betting that elsewhere in this very same celebration of the Weekly's 20th anniversary, there is ample and appropriate coverage of that reporting.

What might be less remembered was the therapeutic working-out in print of my own fear of placelessness. But it was everywhere. Jim Washburn provided a model of Pynchonian depth to which the rest of us could not really even hope to aspire. In our very first issue, he identified the paradox: that we ourselves were like everybody else in Orange County (a point he made by noting that every one of us seemed to have purchased the same black or white Target floor lamp with halogen bulb in upturned dish) and would nevertheless attempt to stand apart somehow, to have our reedy voices heard above the din, like a guy playing dog whistle in the seminal noise band Blue Cheer.

There were others: R. Scott Moxley provided pathbreaking political coverage and media criticism, but his deep dives into the dangers of Little Saigon's anti-communism were equally unprecedented. Gustavo Arellano's first feature was a sociopolitical analysis of Mexican wrestling at an Anaheim swap meet. The aforementioned Paul Brennan examined the meaning of the story of the ghost of Modesta Avila (“Orange County's first convicted felon and first state prisoner,” who, in life, “put a scare into Orange County burghers by defying the most powerful corporation in California”). Nick Schou pulled back the curtain on the OC drug trade, including the rise of violence in Laguna Beach's otherwise-peaceful 1970s-era hippy-surf culture—this latter featuring one of my favorite moments in Orange County history, when a hungry kid wanders the streets of Laguna in search of lunch and his big sister. He finds her in an orgy, enters the mass of writhing, naked bodies, taps her on her absolutely bare back, and asks if she has 5 bucks. “Not on me,” she says.

An overlooked classic of these stories might have been Anthony Pignataro's account of his one-day hike of the entire length of Beach Boulevard, in which he transformed an archetype of suburban sprawl into a kind of living museum of the county's secret history.

The Weekly was also very funny—indeed, at this point in my writing, I'd have already asked Steve Lowery to feed me a punch line. Among Gustavo Arellano's early ¡Ask a Mexican! Q&As was the question “Why do Mexicans sell oranges by the side of the road?” The answer, Lowery offered: “Because Steinways weigh too much.”

Someone once told me that the worst job at the Weekly was to work as a music editor while I ran the paper. That's likely true: I begged everyone on the arts beat (not just music) to offer me more than Biblical/genealogical texts on bands, to forego writing who-begat-whom profiles, but to tell me why this place—supposedly so inanimate/bland—produced the vibrant ska/punk/cowboy/country/metal/pop/rap/surf music it produced. Was there an Orange County sound? And if so, what did it mean—about us, of course, but mostly about me?

I remember with much affection freelance writers I haven't spoken to in years. My nearly lifelong friend Nathan Callahan, who identified the moment when TV news went nuts for live crime drama: the 1951 kidnap-and-murder of a 10-year-old girl that drew to Santa Ana television cameras the size of monsters in Jurassic Park. Lyrical, elegant, incisive Cal State Fullerton English professor Cornel Bonca, who, among his 27 observations on the county fair, offered this one, at No. 4: “Overheard outside the Fair, while waiting for the gates to swing wide on opening day, from the mouth of a 4- or 5-year-old boy, trying to make conversation with, evidently, his babysitter: 'Guess what? Yesterday, my dad got out of jail!'” Rebecca Schoenkopf's first art review (of Christian iconography at the Bowers Museum) now seems the perfect bookend for her much-later profile of a Huntington Beach porn star's remarkably mundane domestic life. Fifteen years after I edited it, the story of Candy Apples still leaves me a little PTS disordered.

Where else were you going to find a writer of Rebecca's sublimity writing Commie Girl, a column that brought radical politics to unashamed affection for local nightlife? Rebecca herself would ask, and then answer such a rhetorical question: “Nowhere, that's where.”

It's true we did not change the entire world. But my colleagues changed me. It would have been impossible to fail while working with them (and may I acknowledge here my wife, Heather, who served as the Weekly's innovative art director almost the entire time I was there—and still managed to raise children?). Many of these people—Matt Coker, Lowery, Washburn, Schou, Schoenkopf, Dave Wielenga, Pignataro, etc.—could have run the Weekly just as well. Gustavo still does. But for a while, they let me run it, and I'm forever grateful.

I left the Weekly in 2007. A few years later, New Yorker writer Tad Friend parachuted into Orange County to become the millionth national reporter (could've been the ninth or 10th) to cover the public-employee pension fight in Costa Mesa. We met, as I had met Vanderbilt, at the Lab in Costa Mesa. We talked pensions and politics, but mostly, I spent the time warning Friend off such antique observations of Orange County as ultimately (and I guess predictably) just peppered his New Yorker piece.

“Costa Mesa has no apparent center,” he wrote in his September 2011 story, “Contract City.” To describe us and this place, he resuscitated Gertrude Stein's respiratorially compromised “no there there.” Costa Mesa “is 45 minutes to forever south of Los Angeles.” The nearby freeways “fling you out to scattered hubs,” “the in-between spaces are a beige blur,” punctuated by “office parks bermed out with Marathon Sod and lone crape myrtles.”

The price of liberty from the psycho-social hegemony of such anti-suburbanism is eternal vigilance. It is easy to fall in hate with our home—to be hypnotized by the swinging watches of The Real Housewives of OC, The O.C., Arrested Development, Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49, misguided radicals at The Baffler and the New Yorker, and even by people in LA who feel about OC what New Yorkers feel about anything west of the Hudson. It is harder to love a place when the incessant/amplified message (rising now to the level of something like white noise) suggests you live on the margins of an empire with its really important centers in Washington, D.C.; New York; or maybe LA. In the moments when you despair, I'd prescribe one copy of OC Weekly. It's free, every Thursday.

CLICK HERE FOR OUR FULL 20TH ANNIVERSARY PACKAGE.

I don’t even understand how I stopped up right here,

however I thought this submit was great. I don’t understand who you’re however certainly you are going to

a famous blogger in the event you aren’t already. Cheers!

Your means of explaining everything in this article is actually fastidious, all be able to simply

know it, Thanks a lot.

Its such as you learn my mind! You appear to understand so much

about this, like you wrote the e-book in it or something.

I believe that you simply can do with a few % to drive the message house a bit, however other than that, this is fantastic

blog. An excellent read. I will definitely be back.

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point.

You clearly know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your

weblog when you could be giving us something informative

to read?

I don’t even understand how I ended up here, however I thought this submit used to be great.

I don’t recognise who you are however definitely you’re going to a famous blogger in case

you are not already. Cheers!