The folks running the Orange County district attorney’s office (OCDA) are now claiming outsiders will help to reform a jailhouse-informant program that won tainted convictions in at least three dozen cases, including death-penalty trials. “Anything we can do to get better as an office, we’re going to do,” OCDA chief of staff Susan Kang Schroeder said in a July 12 interview. “We’re making reforms.” But the sentiment voiced weeks after a CBS 60 Minutes crew arrived on the scene is inconsistent with prosecutors’ antics during the 18-month-old scandal.

Deputy DA Howard Gundy, for example, claimed his office has been smeared by an imaginary “conspiracy” theory. As District Attorney Tony Rackauckas’ representative in a multimonth special evidentiary hearing, Gundy didn’t mask his contempt for Scott Sanders, the assistant public defender who unraveled the cheating. Officials systematically hid exculpatory evidence and employed illegal tactics to trick in-custody, pretrial defendants into making self-incriminating statements to snitches. Symbolic of OCDA group-think, Gundy called the findings “ridiculous” and “outrageous,” deserving of an “F” if they had been written for a law-school assignment.

Perhaps May 2014 best illustrated the agency’s determination to cast Sanders as the villain and thwart future embarrassing discoveries. On May 5, Gundy complained to Superior Court Judge Thomas M. Goethals that prosecutors and sheriff’s deputies tied to the scandal were “suffering the indignity” of facing potential criminal charges if they testified untruthfully. In particular, he sought to derail Sanders’ inquiry of deputy Ben Garcia, but Goethals–a former prosecutor riveted by evidence backing the public defender’s position–refused to interfere.

Garcia sat on the witness stand two days later, telling what Goethals later deemed lies and half-truths. Evidence shows deputies Garcia and Bill Grover, as well as Santa Ana Police Department officer Charles Flynn, negotiated with Oscar Moriel, a serial killer turned informant seeking a generous punishment break. The officers and the thug concocted a July 2009 plan to trick defendant Leonel Vega into making incriminating statements after he’d been charged and had an attorney. As a long-hidden recording reveals, Flynn assured Moriel the deal would remain a government secret. Later asked to explain that arrangement, Garcia appeared to suffer from amnesia.

By that point, prosecutors had spent 10 weeks taking personal shots at Sanders, characterizing his briefs as factless rants, pressing reporters to ignore his work, accusing him of gross insensitivity to crime victims and predicting he was on the verge of permanent public ridicule. That May 7 hearing did serve as a turning point, but not the one hoped by OCDA. Law-enforcement officials could no longer assert their jailhouse actions accidentally violated defendants’ constitutional rights.

During a break in testimony and after Goethals’ departure to his chambers, Sanders’ colleague Tracy Lesage observed Gundy and Dan Wagner, head of the OCDA’s homicide unit, mocking Sanders as a nut who sees conspiracies everywhere. The two prosecutors walked around the courtroom, lifting seats while barking, “I wonder what’s under here?” Garcia then laughed.

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Irvine School of Law, sees nothing humorous. In May of this year, two months after Goethals recused OCDA from People v. Scott Dekraai because he determined they couldn’t be trusted to obey ethical obligations, Chemerinsky made news. He said prosecutors here worked to “undermine the Constitution,” and he demanded a U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) probe. Such reaction, expressed by a nationally recognized legal scholar, rocked Orange County government executives, who worry about future bombshells.

Jim Tanizaki–Rackauckas’ top aide and, in my experience, an honorable man–concedes the informant program wasn’t managed properly. Tanizaki says the Dekraai hearings have produced “significant” reforms designed to ensure discovery compliance with defense lawyers. The office retrained staffers and cops, revised its policy manual, and instituted what he sees as a safeguard: Jailhouse informants must be approved in advance by the DA.

“We are really working overtime to stress the importance of this with our prosecutors and police departments,” Tanizaki told the Weekly. “Our prosecutors need to take affirmative steps to make sure they are in compliance.”

Meanwhile, by July 6–about a month after several national media outlets featured the scandal–Rackauckas acknowledged his office needs outside inspection. He created a “new independent external committee” to “thoroughly” examine his informant program between now and Nov. 30. “It is imperative that police and prosecutors in Orange County use informants only in a lawful manner,” the DA said in a press release.

Members of this committee include Patrick Dixon, a retired Los Angeles prosecutor who has previously praised OCDA and whose wife, Diane, was endorsed for office by Congressman Dana Rohrabacher, a longtime Rackauckas/Schroeder pal; retired Orange County judge Jim Smith, who served on the bench with Rackauckas and in OCDA when both were junior staffers in the 1980s; civil lawyer Robert Gerard, a past local bar-association president and board member at the ritzy Balboa Bay Club in Newport Beach; defense lawyer Blithe Leece, a former LA deputy DA who also worked as a prosecutor for the state bar; and Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson.

“They all have sterling reputations in the community,” said Schroeder, who explained committee members were chosen for their “particular sets of skills.” Two members will be paid: Gerard will get $210 per hour with a cap of $50,000; Leece’s rate is $125 per hour with a cap of $25,000.

While not attacking the members, Sanders sees a ploy. “Mr. Rackauckas may want the outside world to believe there is a true desire to address these serious issues, but the problem is, for 18 months, he and his prosecutors have been angrily telling everyone who would listen that they are the victims in the scandal,” he said. “No one has been held accountable–even those deputies who committed perjury while hiding evidence.”

The public defender questions whether committee members, “even with good intentions,” will have “investigative powers and resources to bring justice to those who’ve already been victimized by OCDA and sheriff’s deputies.”

Schroeder says the committee enjoys “free rein” to see “all the information they want,” can create its own timelines, and is immune from a Rackauckas veto blocking their findings.

“Tony won’t get final say,” she said. An attachment to the contract with the committee calls for members to “objectively proceed with its work not to be influenced by politics, the media, the District Attorney or OCDA personnel.” However, paragraph 20 states that members “will not issue any news releases” without “first obtaining review and written approval” by Rackauckas.

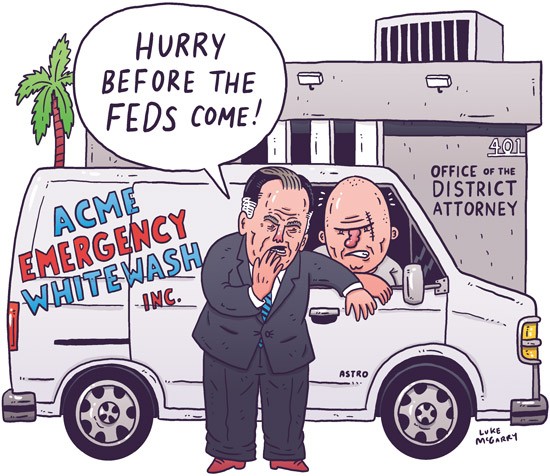

Is the panel a diversion designed to convince DOJ officials in Washington, D.C., they can ignore the mess? The question made Schroeder laugh. “How could we ward off the feds?” she replied. “If they come, we’d welcome them.”

The chief of staff can’t be accused of any criminal wrongdoing in the scandal, but that confidence has a familiar ring. Before the FBI and IRS arrested him for public corruption in 2007, then-Sheriff Mike Carona acted worry-free. He was sentenced to 66 months in federal prison.

The Washington Post’s Radley Balko, who specializes in criminal-justice reporting, believes Orange County needs a new wake-up call. “At a minimum, there should be mass firings of cops and disbarments of prosecutors, past and present,” Balko wrote on July 13. “A system that still retains some integrity would also have the worst offenders in handcuffs.”

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.

One Reply to “OCDA’s Office Thinks Review Committee Will Save It From Snitch Scandal”