Never play poker with Ken Zhiyi Liang. You wouldn't be able to gauge the strength of Liang's hand based on his expressions. During a four-day, bench trial last week, the 38-year-old Irvine civil lawyer sat wide-eyed but stone-faced as the defendant in a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) investigation of a Chinese birth-tourism scandal.

Liang–charged with three obstruction-of-justice-related charges for trying to sneak a material witness in the probe back to China–let James D. Riddet, his defense lawyer, bring the enthusiasm. Riddet, a resourceful veteran more at ease in a courtroom than his two, younger prosecutorial opponents, threw proverbial wrenches at the government's case. He argued DHS agents entrapped his client, falsified a document, botched Mandarin translations from surveillance recordings and could not prove the charges beyond a reasonable doubt.

]

Over the past couple of decades, Southern California defense lawyers have been skillful at undermining the strength of supposedly foolproof government audio and video evidence. For example, think of the Rodney King police-beating criminal trial in which jurors were convinced their eyes and ears couldn't be trusted. Riddet aimed for a similar outcome with three and a half hours of Liang recordings, the heart of the case for assistant United States attorneys Joseph B. Widman and Jerry C. Yang.

After DHS agents conducted a highly publicized, search warrant raid in March in Irvine, Du Li–one of the hundreds of young, non-English speaking Chinese women who've come to the U.S. in recent years to give birth so their children would automatically secure American citizenship–became labeled a material witness in the probe. Li was asked to cooperate by giving statements, offered immunity for committing visa fraud, and ordered by a magistrate judge to remain in this country until she'd been given permission to leave. As with other material witnesses, she hired Liang as her lawyer.

The gambler Liang quickly emerged. On April 4, two of his clients–Jun Xiao and his wife, Long Jing Yi–fled back to China with Liang's clandestine assistance and a cover story that provided plausible deniability. Ten days later, federal agents learned that a third Liang client, Ying Wu, planned to board a plane the following day. During a sealed April 14 hearing, they obtained an arrest warrant for Wu and got Liang removed as Li's attorney. Most important, Liang was left in the dark about the developments, but there's no doubt he wondered if he'd become a government target.

Eager to gain permission to return home with her baby boy, born March 29, Li agreed to become a government agent against Liang. She recorded their phone conversations and face-to-face meetings. In a May 8 conversation, the lawyer told Li she “cannot go back” to China without permission, but, angling for additional fees, he also simultaneously insinuated there might be a way, saying, “Let us think and consider it.”

The rest of the call was a cat-and-mouse game. Li said she still possessed her passport. Liang replied, “Ahhh, very good.” Then he explained that while he might not be able to give her direct advice, he could outline how Xiao and Yi successfully escaped.

“They departed surreptitiously,” said Liang. Li asked if he could help her the same way and received a lawyerly answer: “Generally speaking, based on my experience and competency, I should be able to accomplish that, though no guarantee–but should be doable.”

[

Li asked point blank if he'd help her flee the U.S., and Liang replied, “I cannot help you return to China; otherwise, I would commit a crime.” Despite that statement, the conversation eventually shifted to fees. Liang told her Xiao wanted to pay him $7,000 before leaving the country on a ruse that had him and his wife traveling to Northern California for a conference.

Li wanted to know if she could pay him $6,000 for arranging her escape. The lawyer replied, “Uh, $6,000 would be fine.”

She asked a follow-up question: “Would $6,000 get me out of here 100 percent?” Liang quickly answered, “Yes, 100 percent!”

Four days later, Liang added pressure by telling Li, who still hadn't paid the fee, that an unsuccessful escape could result in her being placed in a room with other inmates, strip-searched and denied basic necessities of life. “You would be treated like a criminal,” he said. “People would push you around, [and] you would sleep on [a] very hard, small, cold bed.”

He then slyly provided a way to avoid such a nightmare. “I cannot directly tell you the method. I can only say [there are] a few methods, and then you can listen to it, and then, like this, if you understand the method I gave to Jun Xiao, you might use it as a reference, but you must never, never say that I told you and tell you to do it this way because it is illegal and I might be arrested.”

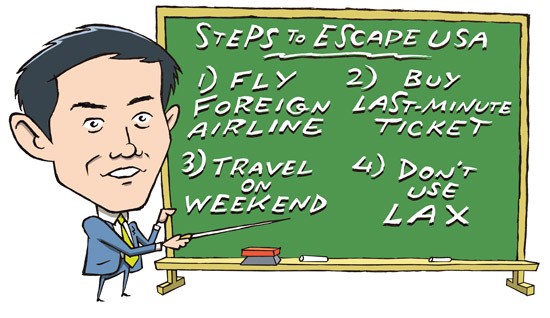

Nevertheless, Liang advised her on how to lower the risk of being caught fleeing: Communicate only on WeChat or with an unregistered, throwaway phone; purchase last-minute tickets; use a foreign-based airline; travel on the weekend; and fly out of a smaller airport than Los Angeles International, where DHS agents are plentiful. He hadn't guessed. Customs and Border Patrol agent Calmen S. Lee agreed to testify to the potential validity of the tactics, noting the moves could help thwart undercover tailing of suspicious characters in the airport as well as the value of passenger manifests normally distributed to law-enforcement agencies 72 hours before a flight.

Liang's advice wasn't given out of generosity. He also told Li his plan required three other men (a middleman and two drivers), each of whom would need to be paid thousands of dollars.

Li: Including you, there would be

four people?

Liang: Right. They are reliable and very trustworthy. This situation is quite complicated, but if it proceeds without issues, they can do what they do.

Li: Equal to 100 percent that I can return to [China], right?

Liang: Right.

Despite the damning strength of those recordings, Riddet told U.S. District Court Judge Andrew J. Guilford that it wasn't clear his client's statements pertained to helping Li flee the country and that he'd taken “no substantial acts” to commit any crime. He asserted, “Talk is not enough.”

Yang wasn't impressed.

“The conspiracy has been demonstrated,” he said. “The defense is basically trying to introduce confusion into this.”

Riddet is a fine lawyer, but he erred by not convincing Liang to agree to a pretrial guilty plea deal that likely would have resulted in a weaker punishment. Or seeking a hung jury by convincing one or two rebellious jurors the government committed entrapment. Within minutes of closing arguments, Guilford ruled Liang guilty on all three counts.

Riddet then pushed to keep his expressionless client free on the existing $1 million bail until a Dec. 14 sentencing hearing. “He's not going anywhere,” he argued. “He's got family and kids here.”

Guilford didn't buy it, especially because the case involves unlawful flight. He said, “Detention is necessary at this point.” Liang now faces a maximum punishment of 21 months in prison and disbarment.

Follow OC Weekly on Twitter @ocweekly or on Facebook!

Email: rs**********@oc******.com. Twitter: @RScottMoxley.

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.