If you were the child of Mexican immigrants from the late 1970s through the 1990s, there was one song you hated above all others. It didn't matter if you were straight from the rancho or the suburbs, a pocho or cholo, boy or girl, fluent in English, Spanish or both: young mexicanos of all backgrounds were united in their loathing of “El Burrito de Belén,” (“The Little Burro of Bethlehem) which almost everyone called “Mi Burrito Sabanero” (“My Little Savanna Burro”).

Originally composed by Venezuelan musician Hugo Blanco and most famously recorded by children's group La Rondallita in the mid-1970s, it sounds to the untrained ear like kid's music at its most horrible—a Barney and Friends fiasco gone south of the border. Starting with a tropical jaunt that mimics the trot of a donkey, “El Burrito de Belén” quickly descends into caterwauling. The lead singer's prepubescent falsetto goes on and on about a damn “burrito sabaneeeero” (an adjective Mexican moms had to explain to their U.S.-born mijos) while the chorus chants “If you see me/If you see me/I'm on my way to Bethlehem.” Then comes the infamous bridge, which consists of kiddies peppily chirping “Tuki tuki tuki tuki/tuki tuki tuki ta,” then a line, then “Tuki tuki tuki tuki/Tuki tuki tuki tu.”

Here, take a listen:

Annoyed yet? Now, imagine hearing the song non-stop from the Feast Day of the Virgin of Guadalupe through the Día de los Reyes Magos (The Feast of the Epiphany for non-Papists), forced upon you by adults in their own version of A Clockwork Orange's Ludovico technique. Imagine trying to play cool among your gabacho pals in elementary school, then melting inside when someone's paisa parent played the record for your classroom Christmas party. “El Burrito de Belén” bore down into your very psyche, an earworm with no remedy that signified everything uncool for kids trying to become American: backwards, hokey, and in español. In other words, Mexican.

I despised the track for decades, and even mentioning it to Latinos of my generation inspires vigorous, simultaneous groans and repulsed head shakes. But some time back, I tried something: I listened to the song, and attempted to place it in its proper context. I remembered my working-class childhood, when buying an album for my mom cost money we didn't have. I imagined the mentality of my parents and aunts and uncles spinning that record again and again, desperately trying to teach the young Arellanos and Mirandas the holiday traditions of Mexico. I imagined their hearts quietly breaking every time us Americanized kids rejected “El Burrito de Belén” in favor of “Frosty the Snowman” and “Jingle Bells.” For them, it was the sweetest tune possible—a song about children on their way to see the infant Jesus. For us, it was just dumb.

If you're a Mexican-American and tears don't well in your eyes when doing the above exercise, then you're as much of a sociopath as Donald Trump. I now admit it with no shame: I love “El Burrito de Belén,” and bawl every time I hear it. It's impossible not to as an adult, because the song is a miracle on many levels. In a region where people barely speak the same Spanish, let alone share a culture, it's one of the few collective Latino anthems, sung ad nauseum during church processions and parties and recorded by everyone from Mexico's Pedrito Fernández to bachata megagroup Aventura to rock en español god Juanes—and even he couldn't get through the tuki-tuki part without sheepishly smiling.

Beyond the chintzy music, the attraction are the multiple themes at play. “El Burrito de Belén” straddles the line between the secular and the sacred, the classical push-and-pull of all Christmas songs. Unlike most explicitly Christian carols, which veer from the somber (“Silent Night”) to the triumphant (“Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”), “El Burrito de Belén” is three minutes of unapologetic joy. But unlike the godless romps of the modern era, the tune never loses sight of the reason for the season—hell, that's the whole point of the song.

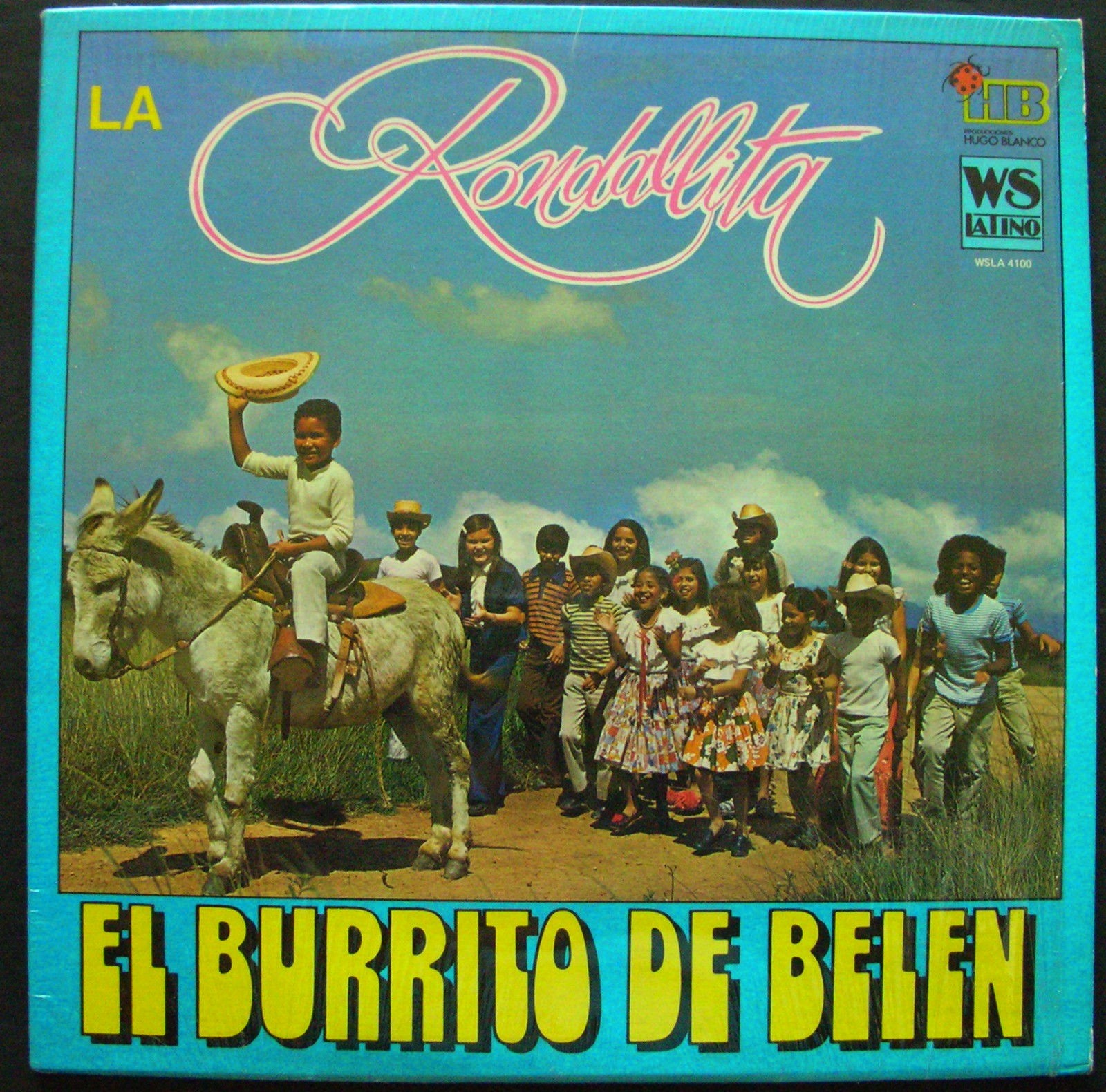

And it's in that angle on Jesus where “El Burrito de Belén” reflects its politics. Written at a time when the Catholic Church hadn't yet declared war on liberal theology, composer Blanco takes a decidedly proletarian view of salvation. The protagonist is a poor boy, as evidenced by him riding a donkey, the animal traditionally associated with Mary and Joseph's travel to Bethlehem (even though it's never specified in the Bible how exactly they got there). The boy's beast of choice foreshadows Jesus riding into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday on a donkey, and the bad, passionate singing (meditating on the song can't change that fact) of La Rondallita is a reminder that those who aren't like children will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Indeed, La Rondallita's LP cover featured a rainbow coalition of Venezuelan country kids seeing off their friend.

Yet despite the overt religion in “El Burrito de Belén,” you don't have to believe in Christ to enjoy its message—like the Nazarene, la canción welcomes all to its embrace. The closest English-language Christmas carol to it is “The Little Drummer Boy,” a song that, not coincidentally, Americans also see as hokey for its clumsy onomatopoeia. Unsurprisingly, both songs deal with downtrodden children—never a popular Christmas theme, never mind the whole away-in-a-manger thing. And while “The Little Drummer Boy” is sweet, you barely hear it anymore because it's so meek—the antithesis of its Venezuelan cousin's loud, assertive witness.

And just for kick's here's Aventura's version:

As an adult, you learn to appreciate “El Burrito de Belén” even more. You treasure finding the album at Amoeba, remember the Navidad fun you had growing up. You even learn about the sad fate of its lead singer Ricardo Cuenci, whose all-out effort as an eight-year old you finally appreciate as artistry in its own right. Colombia's El Tiempo daily found him in 2006 as a 40-year-old common laborer trying to support six kids and with two jail stints under his belt. He had never received payment for his immortal part, let alone royalties, “My life has been hard,” he told the newspaper, embarrassed at his failure to live up to the song's promise. “I've wanted to go on television to say that the 'burrito sabanero' exists. I want people to know, that I'm a man with a good heart.”

It's as if Cuenci acknowledges what only age can teach you: “El Burrito de Belén” is innocence personified—in other words, el niño Jesús. To think anything negative of it is just wrong. So now when I hear it played for younger cousins and the toddlers of my friends, and they get a cara de fuchi, all I can do is smile. And weep.

Very soon this website will be famous amid all blogging and site-building viewers, due to it’s nice articles

Hi excellent blog! Does running a blog such as this take a lot oof work?

I haqve absolutely no knowledge of computr programming however I was

hoping to start my own blog in the near future.

Anyways, should you have any suggestins or techniques for new blog owners please

share. I kniw this is off topic neverthelpess I simply needed to ask.

Thanks a lot!