Entire years, entire careers, entire lifetimes have been spent writing about Chinese cuisine, and yet it's arguably the cuisine least well-represented in the vast bulk of America. As hard as it to hear, the Chinese food that comes delivered in those little white Tetra-Paks™ with the red pagodas and the wire bails would be completely unrecognizable to someone leaving China for the first time.

]

Quick, what's the staple grain for Chinese people? Rice? Not if you live in the north; they eat wheat up there, because it's simply too cold to grow rice. What's the default meat? Pork? Not if you live in the west and northwest, where the population is Muslim and lamb is consumed.

Chinese cuisine is so colossal as practically to defy classification. The country itself is huge, stretching from the Central Asian steppes in the west to the marshy fens of the east, from the forbidding mountains and steamy valleys of the south to the frigid, Siberian north, and there are dozens of culinary traditions. This sort of guide can only give the barest overview of one of the world's most ancient, most mature, most steeped in tradition cuisines.

So what's it like to eat in a real Chinese restaurant, then?

Walking in, you may notice signs (only in Chinese) on the wall; these are normally the specials of the house, so don't be shy about asking what they are. Depending on the size of your group, you'll be seated at a table with a spinning lazy Susan in the middle. Plate, rice bowl, teacup and chopsticks will be put, occasionally unceremoniously, on the table and you'll be handed menus. The server will probably just pause in front of your table; this is your cue to order.

Chinese food is always, always, always served family-style. (If you see individual portions plated with rice and a fried egg roll, you are in a Westernized place.) Order like the Chinese do. If you're hungry, order one dish per diner and one for the table; if you aren't, order one fewer dish than there are people at the table. (If you're hosting, err on the side of generosity.)

Some aspects of Chinese restaurant service, on both the diners' part and the waitstaff's part, come across as unspeakably rude to Western eyes. Waitstaff are summoned by gesturing and spend only as long as necessary at the table. More tea is requested with an upturned teapot lid; waitstaff may move plates in order to make room for more dishes on the table. Imperious behavior, which is not uncommon, can turn into shouting, particularly in less refined places. Regardless of the behavior you see, treat your server with respect, but don't be timid about what you want or you may find you don't get it.

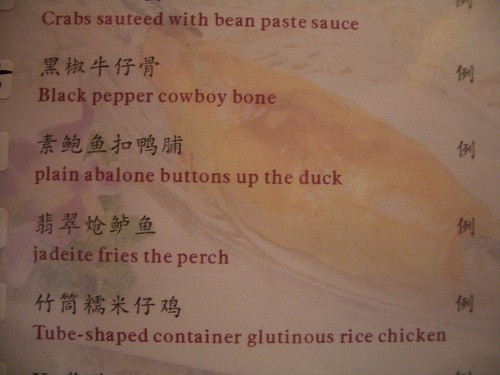

Another barrier to entry is the menu. It's no secret that Chinese menus are often badly translated; entire websites have grown up around the fractured English (or French or Spanish or German) of a Chinese menu. Dishes may be given fanciful but uninformative names such as “Ants Crawling Up a Tree” or “Gong Bao Three Flavors”, communication of allergies can be problematic, and forget about a refund if the dish isn't to your liking. Hence, this introductory guide to Chinese cookery, with characters you can print out if you're nervous about translations.

There are relatively few rules of etiquette in a normal Chinese restaurant. Rice bowls may be held under the chin and the rice shoved into the mouth with a swipe of the chopsticks. Bones and other detritus may be placed on the plate. Slurping is commonplace. (Burping is less common, regardless of what the books from 40 years ago may say.)

Don't ever leave chopsticks pointing out of a bowl, particularly a bowl of rice; it symbolizes the offerings to the dead. When eating whole fish, lift the bones off the bottom fillet instead; turning the fish represents a boat capsizing. Order things in sets of 8, never 4 or, worse, 14.

In certain restaurants, particularly if you are with a group of Chinese people, your dishes may come with a large or differently-colored set of chopsticks. These are service chopsticks, meant as a polite way of serving food from the communal dish without using implements that have been soaking in saliva. If there are no service chopsticks, you may see people using the “butt end” of their chopsticks to remove food from the platter.[

Sichuan (川菜)

Sichuan Province, which has a variety of spellings (Szechwan, Szechuan, etc.), is in China's southwest, and is famous as being the spicy food of China's southwest. Many dishes combine the spiciness (“la”) with Sichuan pepper, a flower bud that causes a numbing sensation (“ma”). If you don't want the heat turned down, say, 我不怕拉 (“wo bu pa la”)–I'm not afraid of spiciness.

The best part about eating in a real Sichuan restaurant is the cold appetizers. Some places make you order off the menu; the more interesting places have a cold buffet where you can choose a number of different foods. Just pick a few items; there may be cold cucumbers swimming in sesame oil, impossibly thinly-sliced pig's ears (these are excellent; get over the weirdness), cold chicken with Sichuan pepper (棒棒雞絲), rice noodles with chile oil and pork (擔擔麵), or the awful-sounding “married couple's lung slices” (夫妻肺片), which is actually beef with Sichuan pepper–no lung is involved.

Hot and sour soup (酸辣湯) is one of those foods that ends up on every Chinese menu in the country. When done badly, it's a cornstarchy, gloppy, flavorless goop; when ordered at a real Sichuan restaurant, the soup is thinner, with lily buds (like less acrid onions), bamboo shoots and tofu, and pronounced vinegar and chile flavor.

One of the glories of Sichuan food is the hellish-looking water-boiled fish (水煮魚片) or water-boiled beef (水煮牛肉片). This is whitefish that has boiled for just a minute or two, then been laid in a crock with vegetables, Sichuan pepper, garlic and an improbable number of chiles. Vegetable oil is then heated to just below the smoking point and poured over the entire concoction. The heated oil poaches the contents, like a cross between a French confit and a Swiss fondue. The result is the tenderest fish, overlaid with an impossibly spicy flavor that dissipates almost on contact with your mouth. Just don't mistake the liquid for soup.

Fish fragrance eggplants (魚香茄子) have absolutely no fish in the dish. “Fish fragrance” refers to flavors that are traditional with fish, such as garlic, ginger and doubanjiang (hot bean paste). Long Chinese eggplants are sliced into thick chunks and fried in oil until the skins wrinkle, and then are stirfried with the other ingredients. What comes out is an amazingly meaty, but vegetarian, dish without a trace of bitterness. You may see yu xiang translated as “garlic sauce” and with a variety of meats; it's all the same sauce, and you can hone in on this dish without needing the bad translations by looking for the characters 魚香.

Twice cooked pork (回鍋肉) is a dish of pork belly that has been steamed or boiled, then stir-fried with leeks or cabbage. This is one of the least spicy dishes in the Sichuan repertoire; the overwhelming taste is rich meatiness rather than any particular flavor. This was Mao Zedong's favorite dish and a great introduction to real Sichuan food.

Kung pao chicken (宮保雞丁) is quite possibly the most popular Chinese dish in America, but at a Sichuan restaurant (where it's pronounced “gong bao”) the peanuts used are often soft, there are no diced carrots, zucchini or bell peppers, and the flavor is extremely spicy and numbing, with a hit of Chinese wine to carry the heat even further down your throat. This is the most Sichuan peppercorn-heavy dish in all Sichuan; it is not for the faint of heart or the desirous of Panda Express.

Pockmarked mother's bean curd (麻婆豆腐), normally just advertised as mapo tofu for obvious reasons, is thick chunks of soft tofu and bits of ground pork cooked with chile and chile oil, Sichuan pepper, fermented beans, hot bean paste, garlic and scallions. This dish can be a little bit hard to eat, because chopsticks tend to cut through the soft tofu. Feel free to scoop it directly into your rice bowl, hold it up to your lips, and move it in with a clumsy swipe of your chopsticks.

Finally, if you ask a Chinese person what their favorite Sichuan dish is, chances are they'll say hot pot (火鍋). A Sichuan hot pot–a real, authentic Chengdu-style hot pot–has not one but two broths, separated by a divider. In places where you're given a choice of broths, this split broth is called “loving couple” (鴛鴦). One is a red hellbroth of chiles, and one is a white broth that is mild but absolutely loaded with garlic. You order raw meats, seafoods and vegetables and swirl them around in one side or the other, then dip them in a mixture of sesame oil and spices of your choosing. You can get pretty heated up eating hot pot, so rather than tea, consider ordering soy milk (豆奶) to cool the fires within.

While most of the best Sichuan restaurants in America are in New York, Chong Qing Mei Wei (5406 Walnut, Irvine) sets the bar high; they have the cold appetizer bar and outstanding twice-cooked pork.

This will be a longer series than the others; Chinese food is a hard topic to deal with concisely. Next week, we'll cover Cantonese, including how to eat dim sum and all the whys and wherefores.