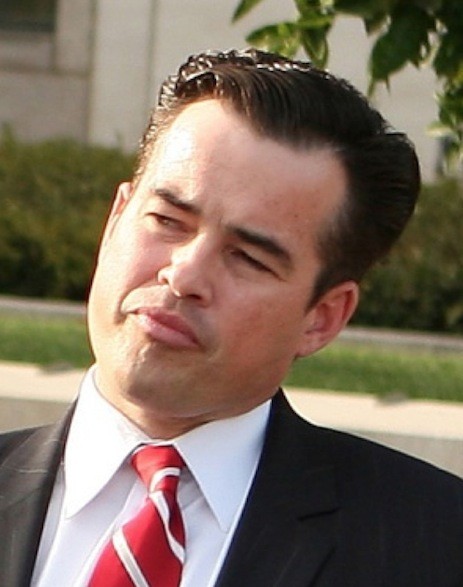

According to the FBI, Aaron Scott Vigil–an accomplished Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) task-force officer in Southern California–and his wife lived luxuriously while spending a whopping $1,600 more each month than their income.

By 2009, the couple had landed in Chapter 13 bankruptcy. They lost a BMW to repossession, faced foreclosure on their home and was in dire need of cash.

A 2011, five-count, federal-grand-jury indictment alleges that’s when Vigil, a Gulf War combat veteran, accepted a $2,500 bribe to participate in a scheme to dupe prosecutors in the Orange County district attorney’s office (OCDA).

Yet the opening of Vigil’s trial last week underscored that while the FBI certainly can prove a con game was perpetrated on the OCDA and $2,500 changed hands as a result of an underhanded scheme, there is no direct evidence, such as an audio recording or a meaningful paper trail, that the DEA agent agreed to take a bribe or received one.

That apparent weakness in the government’s case could make even a crappy criminal defense lawyer look terrific, but Vigil and his alleged co-conspirator, Lawrence Anthony Witsoe–a Vietnam War veteran and Mission Viejo defense attorney with a spotless 40-year career–are armed with superb legal representatives.

Veteran cop lawyer Michael D. Schwartz, Vigil’s attorney, is a mastermind of courtroom strategies, expert wordsmith and talented evidence manipulator. Outside the presence of the jury, a feisty Schwartz has been unafraid to play dubious word games with an unamused, ethics-championing U.S. District Court Judge Andrew J. Guilford, who is presiding in the case. That aggressiveness also landed him as counsel to Jay Cicinelli, one of the Fullerton police officers charged with unnecessarily beating Kelly Thomas to death.

Kenneth B. Julian, Witsoe’s lawyer, is a Manatt, Phelps & Phillips partner who, until June 2009, served as deputy chief of the Orange County branch of the U.S. Department of Justice. Julian’s strengths include not only a quick mind, a gentlemanly demeanor and a solid list of prosecutorial victories that long ago earned him Guilford’s respect, but also that he knows local FBI agents and their tactics and once supervised the two assistant United States attorneys prosecuting Vigil and Witsoe.

Schwartz and Julian aren’t denying the strength of the government’s case–audio recordings of Witsoe repeatedly telling client Wayne Gillis, a Phoenix businessman accused of head-butting a Budget Rent-a-Car supervisor at John Wayne Airport in March 2009, that he had a mystery law-enforcement contact who could secretly influence prosecutors to drop the case in exchange for $2,500.

The defense lawyers also aren’t denying that in several phone calls, Vigil, who was technically a Rialto Police Department cop, encouraged OC prosecutors to give special treatment to Gillis, a native of South Africa, because he had worked for him as a confidential DEA informant.

Schwartz calls Vigil’s recorded lies about using Gillis as an informant “a misunderstanding” in an “ends justify the means” game of the Riverside County-based DEA task-force officer deceiving the OCDA as a way to ingratiate himself to the out-of-state businessman in hopes of converting him into a future informant.

That defense spin caused Assistant United States Attorney Robert Keenan, who is handling the case with fellow prosecutor Jennifer Waier, to contemptuously shake his head; Vigil had never even met or spoken to Gillis–and the Arizona businessman was an absurdly unlikely potential DEA informant. Keenan believes the circumstantial evidence of a bribery scheme is beyond a reasonable doubt. The case is, he insists, “a simple quid pro quo.”

To bolster his contention, Keenan played for the jury audio-recording clips–he called them “Witsoe’s greatest hits”–of the defense lawyer coaching Gillis on the details he should regurgitate about his fake confidential-informant work–including Vigil’s name–if anyone in the government became suspicious of the scam and asked questions.

Witsoe had no clue that Gillis, who was worried he was being encouraged to commit a felony to escape lesser misdemeanor assault charges, had hired a second attorney and that they contacted the FBI about the ruse. Nor did he know Gillis had begun to record calls, save communications and wear a body wire for agents.

When the case eventually got dropped–secretly, at the FBI’s insistence–Witsoe called his client with “the good news,” told him to destroy potentially incriminating email and offered the mindset for him to adopt about the trick on the OCDA: “Nothing was said to anybody.”

The government documented Gillis then sending Witsoe the $2,500 above their own legal deal and the lawyer forwarding that amount to Yareli Campos, the ex-wife of his investigator on the case, Ashraf Swiden.

[This is an important part of the case that the mainstream media blew by erroneously claiming Witsoe funneled the money to Vigil’s ex-wife.]

As it turns out, Swiden isn’t a licensed private detective in California. He’s a bounty hunter, Inland Empire bar owner, and tire and wheel supplier who–drum roll, please–is close friends with an actual narcotics informant for Vigil, according to court records. It gets weirder: Swiden allegedly didn’t have a bank account, so Witsoe customarily paid him for services through Campos, who is the mother of the bounty hunter’s children.

According to Julian, while Witsoe and Vigil pulled “the wool over the DA’s eyes,” there can be no bribery scheme because the rightful, legal recipient of Gillis’ extra payment was Swiden, who was paid to get his buddy Vigil to make the dubious calls to the OCDA without taking a dime.

“Doing a favor for a friend is not illegal,” said Julian, who–along with Assistant United States Attorney Brett Sagel–gained public attention in 2008 and 2009 for the successful corruption prosecution of dirty Orange County Sheriff Mike Carona.

Sadly for Keenan’s prosecution of Witsoe and Vigil, the $2,500 paper trail ends with Campos. In his opening statement, Keenan was forced to speculate that she gave the entire amount in cash to Vigil, who used a portion of the funds to settle a bankruptcy payment, and then wrote a check to her for $900 as compensation for her conduit role.

“Paper trails for cash don’t exist,” the prosecutor explained to jurors.

In his trial brief, Keenan pretends to have achieved a “gotcha” moment by noting sinisterly that 11 days after Campos deposited Witsoe’s $2,500 check, Vigil made a $900 cash bank deposit. The prosecutor’s guessing about the money flow helped to prompt Julian to describe the government’s case as sloppy. He told the jury that the $900 check to Campos was reimbursement for babysitting Vigil’s children.

“There is no evidence any of the [Gillis] money went to Vigil or that Lawrence Witsoe got any money,” said Julian. “The government’s case is based on [wrong] inferences.”

He claims Campos and Swiden will testify that $1,500 of the Gillis money went to pay Campos owed child support and the other $1,000 went toward a kitchen-remodeling project, an assertion allegedly backed by receipts.

“The prosecution wants you to believe there was subterfuge,” Julian told jurors. “But that’s not true.”

Schwartz predicted prosecutors won’t be able to “connect the dots” to prove bribery, and he’s questioning why his client is under attack when government officials should be celebrating Vigil for his ingenuity in developing confidential sources to disrupt illegal-narcotics trafficking.

“[Vigil] liked going after drug dealers,” said Schwartz, who describes his client as “a superstar” among narcotics police. “If he has to play fast and loose with the truth to develop confidential informants, what’s the big deal?”

With seeming sincerity, Schwartz wants to know: If the FBI is entitled to play “a charade” on his client and Witsoe with hopes of achieving a bigger law-enforcement objective–winning a bribery case–what is wrong with Vigil running a charade on the OCDA solely with the hopes of making future big drug arrests?

Preposterous defense-lawyer gobbledygook?

We’ll have to wait and see what the nine women and three men on the jury ultimately conclude about Witsoe, who is free on bail, and Vigil, who, though dressed in a suit during trial, remains locked in the custody of U.S. marshals at the Santa Ana Jail.

Testimony in the case that is expected to last at least another week will resume Tuesday inside Santa Ana’s Ronald Reagan Federal Courthouse.

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.