A whale skull obtained from a beached newborn that could not be saved at Sunset Beach is now helping researchers figure out how fin whales hear sounds, which is a hot topic given the controversy surrounding the U.S. Navy's use of sonar.

]

Navy Sonar Pact with Federal Agency Violated Law and Harmed Marine Mammals: Judge

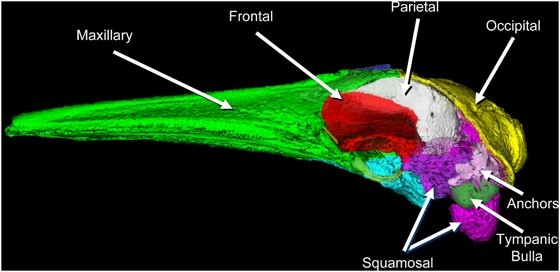

“Fin Whale Sound Reception Mechanisms: Skull Vibration Enables Low-Frequency Hearing” was authored by Ted. W. Cranford, a San Diego State Biology Department grad affiliated with Quantitative Morphology Consulting in San Diego, and Petr Krysl, who hails from UC San Diego's Department of Structural Engineering. Their study is published on PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed, open-access, online publication.

Rescuers from Sea World and the California Marine Mammal Stranding Network tried to save the fin whale but it died during transport, the authors note. Their research indicates that sound vibrations affect the fin whale skull much like the inner ear does on humans and other animals.

[B]y watching the simulated response of the bones in their model to sound, the authors were able to identify two main mechanisms by which fin whales hear. The first, and most prevalent, is known as the “bone conduction mechanism,” where the vibration of the ear bones is caused by the movement of the skull in reaction to sound. The second mechanism is called the “pressure mechanism,” which describes the way sound directly interacts with the whale ear bones after moving through the water and head tissue.

The authors warn their findings only apply to fin whales but given they are a type of baleen whale–which are distinguished from toothed whales by their baleen which filters food out of the water in place of teeth–it is possible other baleen whales utilize the “bone conduction mechanism” as well.

How marine animals perceive sound has been a topic of growing discussion as the amount of man-made noise increases in the ocean. Tools such as sonar, often used by the military to detect objects underwater, have been suggested as a cause of some fin whale behavior that has been interpreted as confusion or even a possible cause of beaching. The authors mention that the results of their study may assist policy-making bodies, to protect our ocean's species from things such as the inadvertent effects of sonar.

There was news about another species of baleen whales earlier this week …

[

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) revealed on Monday that conservation efforts have been so effective that 10 of 14 populations of humpback whales no longer need to be listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

It's a Pacific Life for Humpback Whales

The NOAA is also proposing that when it comes to the remaining four humpback populations, two should remain endangered and the other two should be listed as threatened. Those that would remain endangered are in the Arabian Sea and off Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa and do not enter U.S. waters. Those that would be changed from endangered to threatened are in Central America and western north Pacific waters and do enter U.S. waters at times.

“While commercial whaling severely depleted humpback whale numbers, population rebounds in many areas result in today's larger numbers, with steady rates of population growth since the United States first listed the animal as endangered in 1970,” explains a release from the NOAA, which began an extensive examination of humpbacks in 2010.

“The return of the iconic humpback whale is an ESA success story,” says Eileen Sobeck, assistant NOAA administrator for fisheries. “As we learn more about the species–and realize the populations are largely independent of each other–managing them separately allows us to focus protection on the animals that need it the most.”

If the proposal is finalized, the humpback whale populations that would no longer be listed as endangered would remain protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. NOAA Fisheries has opened up a 90-day public comment period for the proposal. Public comments, information or data, identified by the code NOAA-NMFS-2015-0035, can be submitted electronically via www.regulations.gov or via sea snail mail to: Office of Protected Resources, NMFS, 1315 East-West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910.

Email: mc****@oc******.com. Twitter: @MatthewTCoker. Follow OC Weekly on Twitter @ocweekly or on Facebook!

OC Weekly Editor-in-Chief Matt Coker has been engaging, enraging and entertaining readers of newspapers, magazines and websites for decades. He spent the first 13 years of his career in journalism at daily newspapers before “graduating” to OC Weekly in 1995 as the alternative newsweekly’s first calendar editor.