To the outside world, being a journalist may seem all beer and kickbacks, and granted, there are some perks to the job: we get free stuff; we get to make up stories, print them as fact, and then get a book and/or movie deal after we're found out; and we get access to famous people. Some of these famous people are great; some are accomplished, admired even, while some of them are Marie Osmond and Carly Simon's sister. The point is fame isn't all it's cracked up to be—unless you've never been famous, then it's way better than you could ever imagine. The point is ask any reporter about the famous people they've met, and there are bound to be more than a few stories about famous encounters going horribly wrong; meetings that bristled with disappointment, misunderstanding, boorishness and peeing next to Dave Alvin. The point is John Waters' new movie, A Dirty Shame, reminded us of one of the legendary bad brushes with fame in Weekly history involving Waters and Weekly music editor Chris Ziegler. The telling of that tale inspired the rest of us to tell these stories of fame, disenchantment and Carly Simon's sister.

JOHN WATERS

We were drinking purposefully in the parking lot for about 20 minutes, and then we slid into the Lido Theatre for the Newport Beach Film Festival to see John Waters' Polyester and, if possible, get shitty drunk and act like trash, in the same spirit as the scratch-and-sniff cards they were handing out—to enhance the experience by being the sort of people we ourselves would hope to see at a John Waters movie. So clink-clink-clunk went the poor empty whiskey bottle as it rolled solemnly down the aisle, smacking into the foot of the stage with such an exclamation point that the whole theater giggled. In film school, they'd call that foreshadowing. Then we cheered for Stiv Bators—lamely and without a lot of hard consonants, since it was getting deep into bottle No. 2 or maybe No. 3—and then oops, it was time for open bar at the Hard Rock Cafe. I kinda go through life in a haze anyway, but this was by now an Orson Welles sort of drunk that ably edited out all but the most essential bits of plot, and so without having to waste any consciousness on a boring car ride, there I was with some free something in a glass in a big hot someplace with some people doing stuff. I couldn't tell what, exactly, but I sure could tell that John Waters was right in front of me, and right then, I sure liked him a lot. And there was no reason not to say that really loudly over and over, pausing only maybe to hold my glass up to the light, if those were really lights and not just boozy little slivers of my optic nerves spontaneously combusting, and maybe ask for a refill. I mean, the way I remember it—or the way I remember the parts I remember—is nothing but lovely times until John Waters waves his spotty hand and two big dudes hoist me up by the underarms and—just like the movies!—toss me out on my actual ass, which is something that should happen to everyone at least once just so you can wince knowingly when you see it happen onscreen to Jim Rockford. But I guess I was yelling stuff. I guess I tend to yell a lot of stuff. Somehow I got home (I lived above a liquor store; coincidence, unless God was trying to test me) and I barfed a little blood (see, my mom is freaking out and calling me RIGHT NOW, perfectly synchronized with all the nice girls I know deleting me from their phone books also RIGHT NOW; cheap laughs should really be cheaper), but even now I don't rate it too seriously, and I woke up in the morning when COMMIE GIRL called me up and asked—with a certain relish—what the fuck was wrong with me last night? Was I HIGH? And I wasn't sure who she was because my brain was still lacking a lot of traction, so I—with a certain woozy dignity—said, no, man, I was just regular DRUNK. But the weird thing was I was barely hung-over. You know why? Stupidity metabolizes alcohol. If that doesn't kill you, it'll one day save your life. (Chris Ziegler)

MARIE OSMOND

Grew up watching Donny and Marie Osmond. Never particularly impressed by Ms. Osmond's looks. But all grown up, interviewing her in a Universal City hotel room on the occasion of her starring in a touring production of The Sound of Music, it became apparent to me that this was one hot lady. Now, it was just her and me. Her press person had darted out for something. Probably not coffee. I asked Ms. Osmond some redundant question about what she found interesting about the play. She glanced out a window at the nearby freeway and began answering. I looked down at my notepad to scribble some notes when, suddenly, I saw . . . them. The upper third of her breasticals, ample and full, crying out for release from the hot, sticky confines of her low-cut shirt. Delicious ivory globules. Quintessentially perfect Mormon mammaries. My gaze lingered too long. She stopped talking. I looked up. Her eyes were locked on mine. Marie Osmond caught me looking at her tits. It's never gotten any better than that for me. And I suspect, somewhere in Utah, Marie smiles about it every now and then. (Joel Beers)

[

CHRIS ISAAK

Isaak: Fine-looking boy you have there!

Me[after a 15-second pause]: You betcha! (Rebecca Schoenkopf)

EXENE CERVENKA

Interviewing singer Exene Cervenka is a crapshoot. But I had to, back in 1993 or so; the Action Sports Retailer Expo was in town, and X was set to play the Foothill. She was just as glad to hear from me as if I had Ebola—and by the conversation's end, I wished I did. I opened with a couple of softball questions about her variety store, You've Got Bad Taste, in Silver Lake. Bupkis, like interviewing an Orange County cop. I rolled out the standard “How did X keep the songs and the band fresh after so many years” and got the standard answer, maybe a sentence long. Then as I gasped for words, my brain grasping for the one question that would work, the phone went dead. I freaked, assuming she'd hung up on me. I writhed at my desk until one of us—I think me—called back. I hoped realizing her gaffe would melt her cold, cold heart, but it didn't, so I limped politely through the rest of my questions. That was bad Exene. Still, I love the band, so I got to the Foothill early enough to catch the end of their sound check. John Doe was funny and charming, but when I pulled out my reporter's notebook, he pointed me toward Exene. Aghast, I walked over and . . . it . . . went . . . better. Unbelievably better, as I asked her how much she hated Ticketmaster for a story I was doing about how much people hated Ticketmaster. When I was done, she even asked me if I needed tickets. Where was that Exene when I needed her? (Theo Douglas)

ELMO

There are a lot of bad things that come with this job, and one of them is that one day an editor may ask you to inter- view a puppeteer. I'm not complaining; I knew the risks of the job. Still, when I found out I'd be interviewing the guy who did the voice and movements for Sesame Street's Elmo, I froze. What do you say to that? “You ever get so tired of being cute you just wanna hurt things?” “Does Elmo blame God?” The guy was part of a new, horribly earnest PBS kids show with puppets from all ethnic and differently abled backgrounds coming together to blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So the day comes for the call, and I start talking to the guy about the aesthetic of the puppeteer, how you build a voice to fit a character, how you make sure your new character isn't reminiscent of one so well-known and beloved as Elmo, and I'm feeling pretty good about myself, like I'm going to get through this with my manhood intact. I'll hang up, write a little 12-inch story, leaving my name off it, and hope nobody noticed. Then, he said it. “You know,” and I've forgotten the name of the puppet he was voicing on this new show so let's call him Binky. “You know,” he says, “Binky's right here. Would you like to talk to him?” Binky wasn't there, of course. Binky was in a wardrobe closet somewhere. He meant that he would pretend to get Binky, but really just start talking like him. He wanted me to interview him as the puppet, in full knowledge that I would know that I was not interviewing the puppet but him, a kind of icky shared fantasy that seemed one creepy step up from marionette phone sex (and not a big step, but one of those short, easy steps, you know the kind, like in a step-down den). At first, I pretended I didn't hear him, but he persisted. “Should I get him?” I hemmed and hawed, hoping he would let it drop. “Why don't I get him?” Trapped and panicked, it was at this moment that I told him what I was really thinking—which I never do; I just think it's bad manners and terrifying—I said, “You know, I wish you wouldn't.” “Why ?” “Because it would really make me uncomfortable.” Long silence, though I wouldn't call it uncomfortably long. In my book, every moment of silence was a moment I was not talking to a manpuppet. Finally, he got back to talking to me, his voice reeking a certain what's-it. I asked him an innocuous question. “Gee, I don't know if I should answer that,” he said. “I wouldn't want to make you uncomfortable.” I said thank you, hung up and wrote the story without my name. And then I went home and hugged my kids. (Steve Lowery)

REGGIE JACKSON

I was a cub reporter working for the Anaheim Bulletin, last daily afternoon paper in Southern California. My first sports assignment: talk to former and current Major League Baseball players about former Angels reliever Donnie Moore, who put a bullet in his head a couple of years after giving up a rather noteworthy dinger in the 1986 American League Championship Series. I'd already talked to Carlton Fisk, Jerry Reuss, Bert Blyleven and some other salty vets, so my initial nervousness around real live baseball players was somewhat soothed. I saw the recently retired Mr. October at an Anaheim Chamber of Commerce function and approached him at the bar. He was balding and looked tired. There were two sexy blondes with him. I managed to spit out a “Mr. Jackson?” before he curtly grunted “Whattya want?” I began stammering out a question regarding Moore's death, and before I could finish, No. 44 said, “You killed him!” Me? I didn't even know the guy. “You guys in the media killed him. You drove him to that!” And then he walked away, sexy blondes in sway. I was stunned. Not as much by his words as his breath. It reeked of the good life: cigars, champagne, caviar, sexy blondes. Mixed together, though, it was toxic: as if a ferret had crawled into Reggie's mouth and died, its last request being that its fellow ferret friends memorialize it by shitting on its rotting carcass. This is the stuff legends are made of. (Joel Beers)

BARBARA BOXER

Me[falling into step with her]: Pardon me, Senator? I was wondering what you would say to those on the Left who say that President Clinton has abandoned the poor with his welfare bill. Boxer [screeching]: There is no Left in this country! There is no Right and Left! We're all Americans! And the problem isn't the president! The problem is with people like you asking questions like that! (Rebecca Schoenkopf)

DAVE ALVIN

You only get one chance to pee next to your hero, and I screwed mine up. It happened in 1996 at the recently demolished Foothill Club in Signal Hill; the occasion was a record-release party for Jackpot, the first CD by the Derailers. I got to the trough first and, as Jeffrey Lee Pierce said, was “holding my happiness in my hand” when Alvin, the former lead guitarist and songwriter for the Blasters and who'd produced the Derailers' record, walked in through the tuck-and-rolled bathroom door. My hero. “I really like the new record,” I said. “If anything, they sound even better live,” choosing my words just as carefully as I was, you know, peeing (there are rules to peeing in public; mainly, keep your eyes above the chest and ignore everything else). “What, you don't like the record?” Alvin demanded. “No, no,” I backpedaled, figuratively of course, though I was now frantically trying to shake it and get the hell outta there—God, what had I been drinking? “I just think they're doing a really good show,” I said, hat in hand. But he wasn't in any mood to be mollified, and—bound by pee rules—we both turned away. (Theo Douglas)

ADAM KENNEDY

Me: Adam, your fucking entourage is acting like I'm fucking stalking you! Kennedy: I don't have an entourage. I just came here with Ryan. [Slurring, menacingly] Well, they don't seem to know that. I have to go, Rebecca. It was nice meeting you! (Rebecca Schoenkopf)

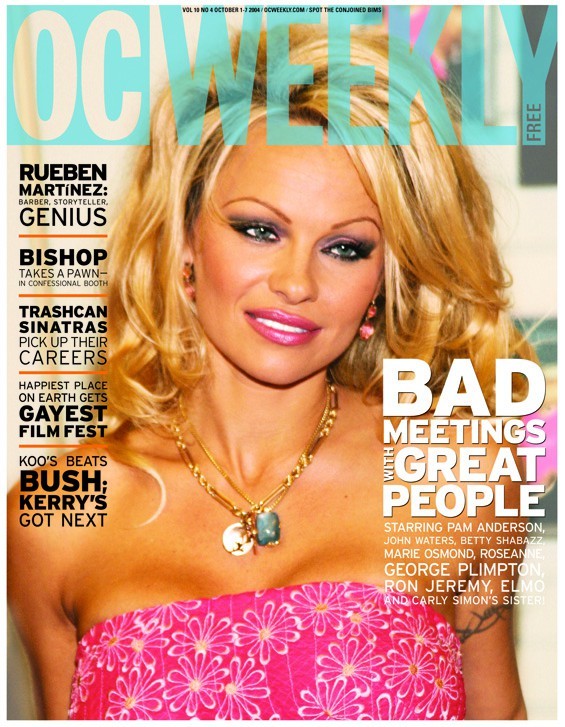

PAMELA ANDERSON

Not that long ago I was working on a story about PETA vice president Dan Mathews, an Orange County boy made good. I drove around LA with Dan, interviewing him between errands, which included casing a KFC for a potential demonstration, when he casually dropped that at the end of the day he would be meeting up with Pam Anderson and would I like to come along. “Um, okay. I guess. Sure. Why not?” (Just so we're on the same page here, this is the Baywatch Pam Anderson we're talking about, not the Pam Anderson who won the 1992 Heisman Trophy; that Pam Anderson was actually Miami's Gino Torretta). So the interview continued—a quite good one actually. Dan is a helluva guy and every now and then he would mention Pam and how wonderful she was, how she was the one who volunteered to help People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals—”They didn't even know what a Pam Anderson was”—how she does numerous other good deeds all undercover with no desire for publicity. So, anyway, this goes on for hours and I'm getting increasingly excited to meet Ms. Anderson but I'm also bracing myself. I've heard too many tales of people meeting some famous/good looking person and being bitterly disappointed to find out that the famous/good looking person is actually much shorter or Scott Baio. So, the time comes and Dan and myself are heading toward the terminal of a private airport—he and Pam were about to jet off to Vegas—and he opens a door and there, standing with a flute of champagne in her hand, is Pam Anderson. Now, I don't know if you've ever had the opportunity to meet Pam Anderson in a private airport, but I highly recommend it. She was funny, smart, self-effacing and, just as Dan had promised, wonderful. She was also generous in her praise of just about everyone else involved with PETA except herself. Oh, and one more thing: She was beautiful; that dazzling kind of beauty that inspires awe but also comfort in that it confirms for you that God is capable of great things when He gets a proper breakfast in Him. Anyways, we talked some more, said goodbye and I went home. This is where it turned bad for me. “So, how was Paaam,” says the wife, in a Pam-and-Steve-sitting-in-a-tree tone. “So, how was Paaam,” says a co-worker, same tone. “Paaam,” “Paaam,” “Paaam.” From every friend and relative who finds out. And they look at you in this leering way, half expecting a massive boner to explode out of your Wranglers at the mere mention of the meeting, but also half expecting the “You know, she really wasn't that pretty,” which, of course, she was. You don't give them the pleasure of either expectation, which disappoints them, which makes them think you are hiding something, that you are not letting something out, that you're suppressing a deranged only-me-and-Pam Anderson-will-EVER-know-what-really-happened-between-me-and-Pam Anderson vibe. This is how it has been for me since meeting Paaam; the cross of her beauty I must bear. I bear it proudly. Gino Torretta? Not so much. (Steve Lowery)

CARRIE BROWNSTEIN

As lead guitarist for Sleater-Kinney, Olympia, Washington's fiercely rocking—and adorable—all-girl trio, Carrie Brownstein has not only established herself as the most darlingest of all critics' darlings, but also serves as a post-feminist style guru/personal savior/girl crush to a bevy of next-generation Riot Grrrls, including yours truly. Through the years, Corin has inspired everything from my haircuts to T-shirts to more than one late-night “Does this mean I'm gay?” chat with God. Still, while I've never been one for maintaining, how you say, “composure” around famous people—just ask Paris Hilton and Peter Gallagher—I never imagined that I, one of S-K's most devoted disciples, would ever go completely batshit in front of them. Besides, I reasoned, it simply couldn't happen. It would, after all, require actually meeting them, and they wouldn't be caught dead anywhere near the OC. No. Just Pomona. Pomona, where my friends Fielding opened at the last minute for Sleater-Kinney; where my pals Aaron and Kevin scored me a backstage pass; where I walked backstage and, at the sight of Carrie Brownstein walking thisclose in front of me, uttered the most incomprehensible, carnal, from-the-bowels-of-my-soul groan ever. You know, like how you menfolk groan when getting a lap dance? Yeah, that groan. She looked over at me. I pretended I didn't do it, shrugged my shoulders and frantically searched for my friends. But as the only other people backstage were her band mates, I was caught. The I'll-never-meet-her-but-if-I-do speech I'd rehearsed in my mind? Vanished. My chance to become best buds with Carrie Brownstein? Kaput. All that remained was what I now recognized to be my unforgivably lame fandom. But God and I both know: she dug it. (Ellen Griley)

FRAN TARKENTON

It was the last day of 1978, the end of my first year as a full-time sportswriter for a Southern California daily and the first time I would meet one of my lifelong idols—Minnesota Vikings quarterback and future Hall of Famer Fran Tarkenton. The Vikings were playing the Los Angeles Rams in the opening round of the NFL playoffs at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. I was assigned to be in the Vikings' locker room after the game, win or lose. Fran was now 38 years old and well past his prime, but this only enhanced his stature in my eyes, which saw him aging with intelligence and dignity. For example, when he got into predicaments now, he tended to toss short passes to running back Chuck Foreman instead of running around as he had done in his heyday. But Tarkenton's magic ran out that day, and the Vikings lost to the Rams 34-10 after mustering only 48 yards of offense in the second half. Tarkenton was overwhelmed by the Rams defense, which sacked him 10 times and rushed in so quickly that he didn't have time to find Foreman with those short passes. I headed to the locker room, nervous, but when Tarkenton stood solemnly before his cubicle in the steamy locker room to field questions from about 15 reporters on deadline, I was the first to ask him. I sort of raised my hand a little, and he nodded toward me. “All season long you've been able to avoid the rush by using those short passes to Foreman, but today it didn't seem that you were able to find him open,” I began. “What changed? Were the Rams using a different defensive scheme? Was Foreman doing something differently? Did you have a different game plan? Or were the Rams simply playing on a higher level?”

Tarkenton looked at me, scrunched his face into an expression of pure hatred and didn't say a thing for maybe five seconds. Then, as he opened his mouth to speak, his lips curled back sarcastically. “Wow, you really know a lot about football, don't you?” he began mockingly. “You know all about what we were trying to do out there, what we usually do, what the Rams were doing. You know all about me. That's certainly obvious.” Tarkenton's voice was getting louder, and as it did, the locker room got quieter. I wasn't feeling so good. I tried to rephrase my question, but he cut me off. “Oh, you've got more to say about how I play football? That's great! That's perfect!” he said. “Here's what we're gonna do, then. I'm going to take a shower and put on my clothes and go home, and you can stay here and answer everybody else's questions for me. Obviously, with you around, they don't really need me to be here.” With that, Tarkenton left—leaving me with more than a dozen colleagues who still had stories to write and suddenly realized they were going to have to do it without Tarkenton quotes. They turned on me, too. Of course, I have hated Fran Tarkenton from that moment, which turned out to be the first moment of his post-football career; he retired a few weeks later. In the 26 years since, Tarkenton has conducted himself like an odious human being, tearing down his legend through a succession of career choices completely in line with the man I met that day in the locker room. Hosting the inane 1980s TV show That's Incredible! with John Davidson was the least of it. He's also lent or sold his name to several lame businesses—including one that cost him a $100,000 settlement from the Securities N Exchange Commission for civil fraud—and wacky endorsements. He wrote a suspense novel, Murder at the Super Bowl, with a ghostwriter. And he has become better known for whining about his lack of recognition than any of the records he set during his career. On the bright side, Fran Tarkenton is now 64 years old and will die someday. (Dave Wielenga)

GEORGE PLIMPTON

Before he died almost exactly a year ago, George Plimpton was something like Ernest Hemingway—a writer who had founded and edited the highbrow Paris Review and, believing that first-person experience was essential to great sports writing (and, further, that sports makes for great literature), had quarterbacked the Detroit Lions, pitched to Willie Mays, boxed Archie Moore, played tennis with Pancho Gonzalez, played in pro/am golf tournaments, performed in a circus and, yeah, fought bulls alongside Hemingway in Spain. And he met me. I was in a crowd of 500 at the New York Public Library—it was 1997 or '98—listening to Plimpton interview novelist T.C. Boyle, who'd been my mentor while an undergrad at USC. They were seated in well-stuffed, low-back armchairs on a stage set like a levitating drawing room, Plimpton's buttery Harvard drawl—more Oxford than Boston—chasing Boyle around the empty rooms of his nihilism. Boyle was Boyle—funny, iconoclastic, contemptuous of humanity—Plimpton was brilliant, and I was like a fat man at the Circus Circus buffet. My two idols sitting up there, 40 percent of my literary Mt. Rushmore—Plimpton, whose writing had inspired me to move from jockdom to writing, and Boyle, who'd seen me through two pretty difficult years as I abandoned entirely the idea of the priesthood and began writing with something like Freud's sublimated sex drive. Near evening's end, during the Q&A, clouds like dirty wool at the library windows, Boyle recognized me in the crowd—about a thousand eyes panned toward me, warmed me—and asked me to join him afterward. I did. He introduced me to Plimpton. Lingering stageside as Boyle autographed books for New Yorkers, I turned to Plimpton. He was a tall man, about six-four I'd guess, with thin white hair and a New Englander's bony mug, courtly. “Your writing in Sports Illustrated made me want to be a writer,” I told him, meaning to sound as grateful as I am. “Really? Is that a good thing?” he asked. “Depends on whom you ask,” I said. “Yes,” he said, “I suppose.” Pause. “So, Tom tells me you're from California?” he asked. “Yes,” I said. “Warm there,” he said. “Yes,” I agreed, “warmer than New York City in March, anyhow.” In just 10 exchanges, the greatest interviewer ever, the man who drew out reticent athletes, moved with me from introductions to the weather and then fell uncomfortably silent. (Will Swaim)

BETTY SHABAZZ

I am not black—something many people notice upon meeting me. In fact, I reckon I may be the least black person this side of Whiteman “Whitey” Whiterwhite—he of the White Plains Whiterwhites—so it was with a bit of trepidation that I took the assignment of chronicling the resurgence in popularity of Malcolm X, who in the early '90s was big, Jim-Morrison-early-'80s big. There was the Spike Lee movie and the reissuing of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. There were the T-shirts and one terrifically cool “X” cap that I greatly admired but, for obvious reasons of comportment, could never wear. I had read the great man's autobiography and, like most others, was moved and inspired by it. I thought it would be a coup to talk to one of the book's main characters: Malcolm X's wife, Betty Shabazz, portrayed in the book as strong yet compassionate, able to keep her family together as forces on all sides threatened to destroy it. Somehow, I found a phone number for her and, through an intermediary, arranged a time to call. Ring. Ring. “Hello?” “Hello, this is Stev . . .” “Hello?” “Uh, hello. This is . . .” “Hello?” This went on for some time; I don't know if the fault was my phone or hers—it was hers—but finally, desperately, I decided to break the cycle. “BETTY?!” It was rash. This she heard. “Do you know me?” she said. “Uh, well, no. I'm the reporter who . . .” “Then where do you get off calling me Betty?!” You know, most people believe a man ceases being a man the day he leases a minivan, but for me it was that moment. I stammered and stuttered, racked with guilt and stupidity and something else that I can't identify but it sure made my pee-pee ache. I apologized, gave some lame excuse, and then segued, I thought, rather drolly into my first question. It didn't matter. She'd hung up. (Steve Lowery)

ROSEANNE BARR

Me: Well, I wanted to ask you how it was to be really poor when you started out, and now you've got all these piles of cash, and I wanted to know how that was going for you. I'm a socialist, and I work in Orange County, so it's interesting for me.Roseanne: Why? Why what?Why are you? How old are you, 19? I'm 28. It's how I was raised. My mom is 58, and she's a Marxist.Well, it's how I was raised, too. My dad was like that. Where did you grow up?Salt Lake City, Utah. I didn't know they allowed communists there!He wasn't a communist! He was a socialist. Close enough for most Americans! [Mean pause] I was raised that way. But I find it to be today another excuse to hate people. Do you mean it's an excuse to hate rich people?It targets somebody as an enemy. It's diversionary stuff. I think that's screwed. We all need to fix ourselves. That's the kind of journey I'm on now. I'm menopausal. Bitter. Old. Deranged. Have you changed because of the piles of money?More than anything, it changed everyone around me. I have the same beliefs I've always had. They've always worked for me, so why change them? One thing about being fantastically wealthy and famous, it allows you to do a lot of good things. I've got a foundation. . . . What kinds of things do you do?I do a lot of things. Things for kids. It's very spiritually fulfilling. So what kind of things will you be talking about in your act?I'm looking to expand my act, make it kind of a theater piece. I'm more mature as a performer now. What do you do with your days? [Snotty] I run a business. I have an Internet business, a studio I make things in. I also have a lot of time to lounge around my pool. I moved out of LA, so there's no show business around me. So could you give us kind of a preview of your act?A preview? What kinds of things you'll be talking about?Well, I just told you! I'll be talking about aging, menopause, hate. Humorous stuff. About being wealthy and fat. The usual jokes, but more mature. You should put in there that I do mind reading now, so if people want to know the future, they should think of a question. Okay, here's one: Is there anything else I should have asked you and didn't?No. (Rebecca Schoenkopf)

LUCY SIMON

I certainly would not categorize Lucy Simon as a “great” person. Oh, I'm sure she's a wonderful wife (if she's married) and mom (if she has kids) and friend (if she has friends). But to be honest, who even knew Carly Simon had a sister? The reason for the chat with Simon—Lucy Simon—was she'd written music or lyrics or somesuch for the Broadway musical version of The Secret Garden, whose touring cast was coming to Orange County from Los Angeles, which is where I would be meeting Simon—Lucy Simon—for dinner. My wife is a huge fan of Simon—Carly Simon—so she tagged along. Believe it or not, but at one time the Simon sisters were equally famous as a singing duo or trio or somesuch. Carly's solo career was launched from that act. Perhaps it's my own insecurities, but when conversations with the famous or think-they're-famous hit dry patches, I immediately blame the lull on the subject of the interview not liking me. As my wife filled the gap by telling Lucy how much she loved Carly, I began to panic, which invariably causes me to blurt out stupid questions, such as: “So, Lucy, does it ever bother you that you and your sister Carly started in the same place, but she rocketed to stardom while you've remained fairly obscure?” From the look on the face of Simon—LucySimon—you'd swear she just gulped a bad clam. My eyes met my wife, who was scowling at me while shaking her head. “Uh . . . um . . . I LOVE MY SISTER!” said Lucy, her voice rising. “I'm proud of what's she's accomplished.” She went on about that as well as her own personal and professional successes for a good five minutes. If she did not like me before, she certainly did not now. (Matt Coker)

GABRIELLE REECE

To most people—that is, outside of the 37 or so creepy old men who actually followed pro beach volleyball in the mid-'90s—Gabby Reece was little more than a six-foot-three pillar of gap-toothed, deep-voiced sports commentary—thanks, MTV Sports!—who, in that strange time of big-haired supermodel demigods, was considered kinda hot—in a gap-toothed, deep-voiced, big-enough-to-be-described-as-a-pillar sort of way. But to the members of Saint Joseph High School's CIF powerhouse varsity volleyball team—oh, the mid-'90s!—Gabby represented the zenith of all that could be attained within the world of women's volleyball: fame, fortune, and a very tight butt. That she and her Nike five-person teammates toured as part of Nike's Participate in the Lives of America's Youth (PLAY) program only increased our respect for her. When word hit that Gabby and Co. were hosting a PLAY volleyball clinic at Manhattan Beach—and offering a chance to scrimmage against Team Nike for a few points—we assembled our five best players for a little extra-special practice and arrived at the beach ready to be schooled. Only it turned out that we weren't the ones who needed schooling that day. Upon being stuffed by our six-foot-one middle blocker, Gabby's gap-toothed grin quickly turned upside-down. As the rest of our team celebrated this once-in-a-lifetime achievement, our middle blocker swallowed a heavy dose of the professionally paid, corporate-sponsored shit-talk Ms. Reece passed through the net. She promptly spit it right back: “Lady,” she said to Reece, “I'm 16. You just shit-talked a 16-year-old. And that's—that's just fucked up.” Roof! (Ellen Griley)

CHRIS ISAAK

Me: Hi! SamandAnitaweretryingtogetbackstagetosayhi toyoubutthebouncer wouldn'tlettheminbut anywayi'mafriendoftheirsandtheywantedtosayhi!Isaak: Sam and Anita? Oh, I'm sorry I missed 'em! But I didn't know Sam and Anita had such good-looking friends! Ummmmm, SamandAnitaweretryingtogetbackstagetosayhi toyoubutthebouncer wouldn'tlettheminbut anywayi'mafriendoftheirsandtheywantedtosayhi! [Repeating himself slowly, since I'm clearly retarded]I didn't know Sam and Anita had such good-looking friends. [After 15-second pause] Yerp? (Rebecca Schoenkopf)