2006 is a strange year to look back on in hip-hop history. Unlike most years which can be pointed to as a “good year” or “lackluster year” for the genre, artistically it’s a time of divisive polarizing high points, all greatly overshadowed by the tremendous commercial shortcomings. Yes, even with the music industry as a whole largely going through a tailspin in the 2000s, rap was facing its hardest threat of indistinguishable industry irrelevance. It was in this particular darkest hour that the hip-hop nation as a whole largely gravitated toward one of two albums that were released on the same day: Ghostface Killah’s and Fishscale and TI’s King. While the artists in question weren’t publicly fanning the flames of competition as their contemporaries 50 Cent and Kanye West would do one year later, the King vs. Fishscale dichotomy is perhaps what defined hip-hop’s 2006.

2006 is a strange year to look back on in hip-hop history. Unlike most years which can be pointed to as a “good year” or “lackluster year” for the genre, artistically it’s a time of divisive polarizing high points, all greatly overshadowed by the tremendous commercial shortcomings. Yes, even with the music industry as a whole largely going through a tailspin in the 2000s, rap was facing its hardest threat of indistinguishable industry irrelevance. It was in this particular darkest hour that the hip-hop nation as a whole largely gravitated toward one of two albums that were released on the same day: Ghostface Killah’s and Fishscale and TI’s King. While the artists in question weren’t publicly fanning the flames of competition as their contemporaries 50 Cent and Kanye West would do one year later, the King vs. Fishscale dichotomy is perhaps what defined hip-hop’s 2006.

It was a weird transitional year for the genre, full of growing pains stemming from both a generation gap and regional bias disenfranchising listeners. New York’s biggest presence was through the quasi-indie Dipset who seemed to straddle the line between mainstream major label mainstay and the direct sound of the streets. Meanwhile, listeners across the hip-hop nation were embracing the wave of the south and the countless sub-genres striking a chord from coast to coast. Everywhere, that is, except New York. In fact, some of the purists of the 5 Boroughs were having a hard enough time accepting post-G-Unit Dipset-era artists for the same anti-commercial reasons the divide between mainstream and underground bred so much creativity in the late ‘90s. Now, however, there was largely splintered stagnancy. There was really only one MC many critically felt New York could get behind, Ghostface Killah.

Ghostface seemed like the perfect pure hip-hop candidate to get behind. A hyper-creative original member of the Wu-Tang Clan who not only had the long-tenured pedigree, but because of how much more attention the more famous members of the crew had received by that point, Ghostface was able to quietly become the most consistent member in the crew without risking over-saturation. By 2006 he’d finally broken through as a burgeoning charismatic pop culture figure, whose one-of-a-kind turns of phrase effortlessly created quotables and emphasized how much fun rhyming in the English language could be. The cross-section of traditionalism and the avant-garde made Ghostface a critical darling who would be welcome to pop up on a track with any east coast artist.

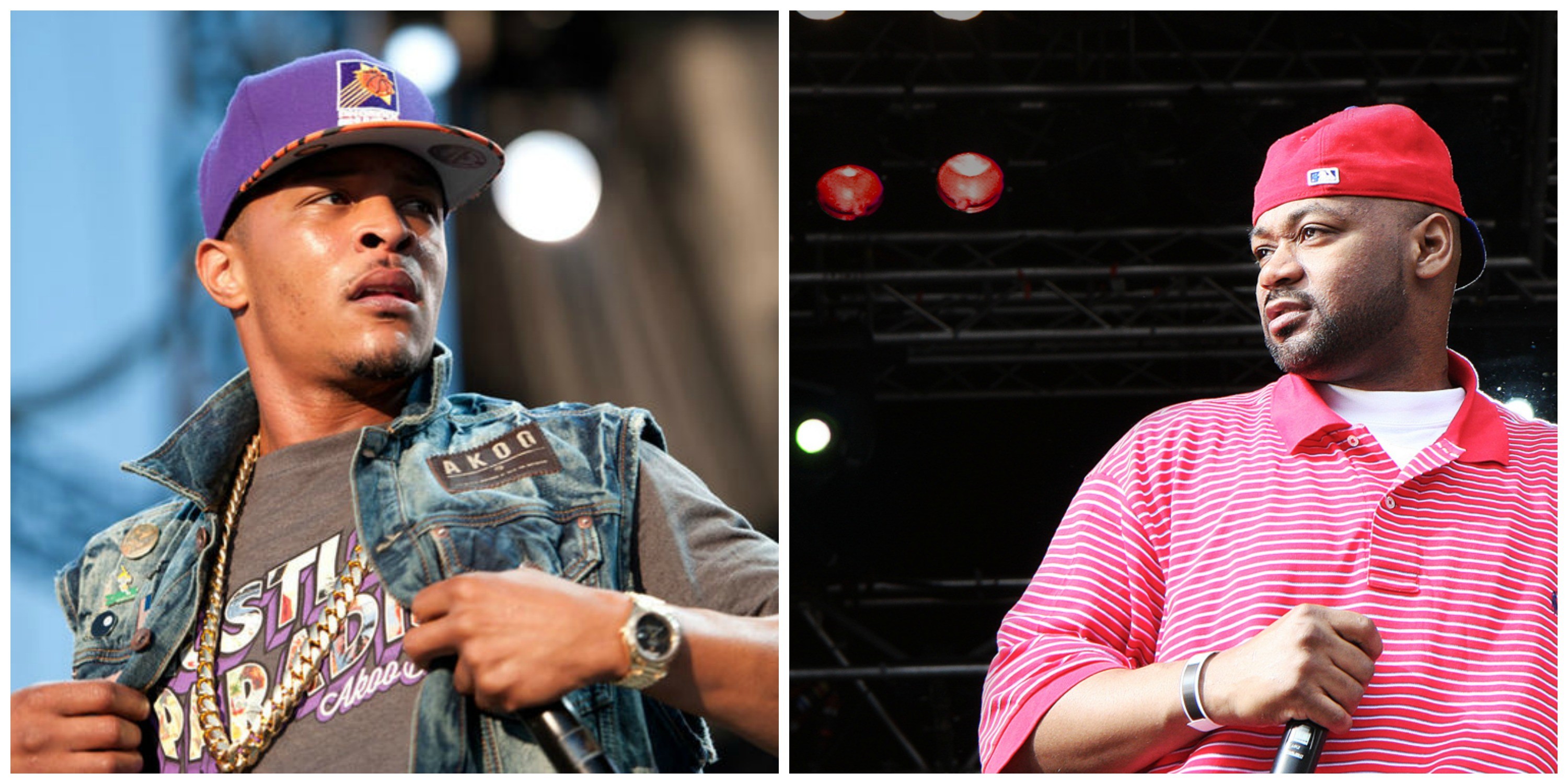

Meanwhile, the King of the South TI was not just winning over legions of hip-hop heads all over the U.S. thanks to the back-to-back success of his Trap Muzik and Urban Legend albums, but was beginning to occupy that “I hate all southern rappers EXCEPT…” qualifier space for southern-phobic listeners who until then had only been comfortable with any combination of Scarface, Ludacris or Outkast. TI had a thicker Atlanta accent than all of them, but could stack syllables lyrically with the best of any region, ultimately sharing a pulse with the rap world at large to create King. Most famous for “What You Know,” one of the decade’s biggest singles, King is nothing short of a masterpiece. It didn’t follow or set trends, it defined them. Defiantly southern production, with cameos from all over the hip-hop map and perfectly structured, there isn’t a misplaced second on the entire project.

Rightfully raved about, King was the only rap album released in 2006 to go platinum. Think about that for a second. Out of every CD released under the genre of hip-hop, this was the one and only release to move a million units that year. For comparison, comedian Dane Cook’s Retaliation sold two-million copies. It’s safe to say that, commercially, TI was carrying the hip-hop industry on his shoulders by himself.

But that same day of release, March 28, Ghostface Killah dropped Fishscale. Just as critically lauded, it sounded as if Ghostface had united all of New York’s hip-hop subsets for one huge unifying release. While the zeal for such a cross-pollination in 2006 was understandably cause for celebration, ten years later the (Tony) stark contrast between the album’s sounds really are a bit jarring. Today, Fishscale sounds like three great EPs all trying to find themselves in each other. You have Ghostface thriving in the traditional classic hip-hop banger lane (the Pete Rock produced “Be Easy,” the Just Blaze produced “The Champ”), the underground flirtations with the eccentric (four MF Doom productions and two from the then-recently deceased J. Dilla) and the mainstream-appealing major label appeasing work that really speaks to the time (the Ne-Yo-assisted “Back Like That”). While there have to be some listeners in the middle overlap of the venn diagram for all of these, for better or worse these tonal shifts are what wind up dating the Fishscale as something of a Ghostface-hosted hip-hop sampler of 2006 New York hip-hop.

Of course, the ever-present asterisk when comparing rap albums in a calendar year is that rap’s a genre that largely hasn’t defined itself with the album medium. With hip-hop in the marketplace originally built on singles, there’s not that many years where the MCs in question hit the studio with the transparent desire to make a “classic album.” For 2006, however, there’s the rise of mixtape culture which allowed artists to have a direct line with their fans to share the music that they wanted to make without typical industry constraints.

That’s precisely why Lil Wayne’s tidal wave of output garnering him numerous “Greatest rapper alive” accolades stemmed from non-album endeavors, namely his mixtape masterpiece Dedication 2. But perhaps it’s the existence of this additional pipeline that exposes more of Fishscale’s flaws as Ghostface’s mixtapes at the time, with names like The Broiled Salmon Mixtape, included not just alternate versions of songs later found on Fishscale, but entire songs like the MF Doom-produced “Charlie Brown” that had to be cut entirely. As active as T.I. was on the mixtape circuit as well during this period, comparable concessions can’t really be heard on King. Still, paired side-by-side, King and Fishscale cover an entire spectrum of an overlooked era, and now that there’s as much time between their release and now as there was between then and rap’s tumultuous 1996, the two’s achievements tell a new story.