As you've probably gathered if you've read

my rave review of the current Bowers Museum exhibition on the life of

Benjamin Franklin, I've become a bit of a Franklin enthusiast overnight. So profound is my admiration for the show–and for Franklin himself–I rented documentaries from Netflix and spent the weekend on the Internet reading just about anything I could find on him. When the Bowers' cheery publicist,

Rick Weinberg,

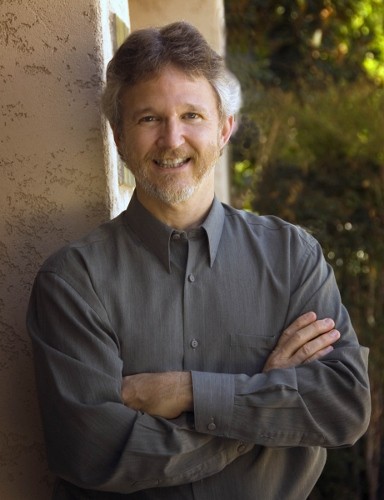

offered to put me in touch with the exhibition's consultant scholar, UC San Diego professor of political science

Alan C. Houston (an authority on all things Benjamin), I took the opportunity to try the limitations of my newfound knowledge and asked the professor to tell me all the dirt he knew on the Founding Father.

“The good particular men may do separately . . . is small, compared with what they may do collectively.”–Benjamin Franklin

]

OC Weekly (Dave Barton): You've written two books on Benjamin Franklin. What was your introduction to him and what lead you to focus your writing on him?

Professor Alan Houston: Like most Americans, I was introduced to Franklin as a child. Everyone knows how he flew a kite in a thunderstorm, right? It was not until graduate school, however, that I read the

autobiography, and I began to appreciate the extraordinary richness and sophistication of Franklin's life.

My professional identity is a historian of British and American political thought during the 17th and 18th centuries. I'm interested in the origins of democracy, in the emergence of liberalism and in the spread of republicanism. In 2000, I began work on

Franklin: The Autobiography and Other Writings on Politics, Economics, and Virtue (Cambridge, 2004). In the course of preparing this edited collection, I gained an even deeper appreciation for Franklin's originality and importance. He understood, better than most, the moral and political challenges of modern commercial societies. The world–his world, but also our world–was constantly changing. New discoveries might lead to improvements in the quality of human life. There could be no substitute for individual industry and cooperative effort.

Speaking of books, Franklin's entire life seems to have been heavily influenced by the written word, as an autodidact, printer and author. Can you discuss why you think this was such an influence on him?

Franklin's formal education was limited to two brief years. He learned to read at a very early age–so early, in fact, that he could not recall a time when he could not read. As a child, he later recalled, “All the little money that came into my hands was ever laid out in books.” We tend to think of Franklin printing newspapers, founding libraries, experimenting with electricity and negotiating with foreign countries. But before Franklin became a doer, he was a reader. He remained an avid reader throughout his life; at the time of his death, he had a private library of nearly 5,000 books.

They were sources of knowledge, understanding, inspiration and example. And they made it possible to communicate at a distance. Franklin helped found the

American Philosophical Society (APS) in 1743, which was the first learned society in North America. The APS was intended to facilitate experiments and discoveries in every field of study. To make that possible, scholars, scientists and explorers throughout the colonies had to be able to communicate with one another. Today we might use e-mail or the Internet; in Franklin's day, it was the printed page that enabled people–it was separated by space and time to cooperate in a common endeavor.

It seems Franklin was away from his wife much of their life together, and he had a reputation–not really touched on in the Bowers exhibition–as a ladies' man. What was the Franklins' relationship like?

I would call it a “companionate” marriage. Their relationship was shared in affection, interests and responsibilities of running a household. And by “household,” I mean not just raising children, but also managing Franklin's printing business and sustaining his career as scientist, politician and civic activist.

Comedian Bill Maher recently took the Tea Party to task on their perceptions of the Founding Fathers: “They were everything you despise,” said Maher. “They studied science, read Plato, hung out in Paris and thought the Bible was mostly bullshit.” Thoughts?

As a young man, Franklin delighted in arguing with other people. He was brash, aggressive and self-satisfied. He found that in winning arguments, he has made enemies. As a consequence, he gradually set aside his “positive dogmatical manner” and learned to express himself with modesty and humility: “To this habit . . . I think it principally owing, that I had early so much weight with my fellow citizens when I proposed new institutions or alterations in the old, and so much influence in public councils when I became a member.”

Straighten us out on a couple of popular misconceptions of Franklin.

Three popular misconceptions: That he was a crass and boorish apologist for making money, a shameless skirt-chaser and that he was the “first” American–the epitome of our national identity. Instead: He was a lively companion (with a love of wit both high a low); he was a vibrant public intellectual that consciously committed to both learned controversies and civic policies; and that he was a cosmopolitan. Franklin was deeply indebted to ideas and values circulating throughout the Atlantic world.

Share your favorite Franklin anecdote with us.

Taken from the Autobiography and in Franklin's own words: “I believe I have omitted mentioning that in my first voyage from Boston, being becalm'd off Block Island, our people set about catching cod and hawl'd up a great many. Hitherto, I had stuck to my resolution of not eating animal food; and on this occasion, I consider'd with my Master Tryon, the taking every fish as a kind of unprovok'd murder, since none of them had or ever could do us any Injury that might justify the slaughter.–All this seem'd very reasonable.–But I had formerly been a great lover of fish, and when this came hot out of the frying pan, it smelt admirably well. I balanc'd some time between principle and inclination till I recollected that when the fish were opened, I saw smaller fish taken out of their stomachs. Then thought I, if you eat one another, I don't see why we mayn't eat you. So I din'd upon cod very heartily and continu'd to eat with other people, returning only now and than occasionally to a vegetable diet. So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for every thing one has a mind to do.”

I found Franklin's embrace of “mutual aid” very inspiring in the exhibition, with its focus on working together to care for one another almost socialist in tone . . . or at least drastically far away from a kind of laissez-faire capitalism. Can you discuss how he came to that understanding? Feel free to tell me I'm completely off-base here, as well.

Not “socialist” in an economic sense, but “social” in the sense that civic improvement rests on cooperation with others. For example, he was the first person to present a developed plan of federal union for the colonies of North America (the Albany Plan of Union of 1754). In a famous cartoon that he drew at that time, a snake is shown cut into pieces, with each piece labeled a different colony. The phrase underneath: “

Join, or Die.” Twenty-two years later, he drew a design for paper money to be issued by the Continental Congress. A chain with 13 links, each bearing the name of a colony, surrounds a ring labeled “American Congress,” and in the very center are the words “We Are One.” Like the links in a chain, each colony was distinct; but as in a chain, each link was dependent on its connection with the others.

What were Franklin's feelings about his rampant celebrity during his tenure as America's Ambassador to France? What do you chalk that celebrity up to?

Personally, he was ironically amused. Politically, he understood the power of images, and the image he had in France–a brilliant scientist whose wisdom was “natural” (not due to high birth, or social privilege, or higher education)–was a source of tremendous power.

I was intrigued by Franklin's comment on the Constitution quoted in the exhibition: “I confess that I don't entirely approve of this Constitution at present, but Sir, I am not sure I shall never approve it. . . . Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best.” Was Franklin being cheeky here, or was he hedging his bets? Did he have serious concerns about the Constitution?

This speech was intended to persuade members of the constitutional convention to set aside their differences and unanimously endorse the final document. Franklin's skepticism is sincere. He understood that reason is fallible–not just the reason of others, but even his own.

Franklin was a unicameralist; he thought that the national government should, like the Pennsylvania state government, have a single legislative body. This did not prevent him from helping steer the Convention toward the “Grand Compromise,” which permitted individuals to be represented in the House and states to be represented in the Senate. Compromise was essential to improvement.

While the exhibition was hardly hagiography, it seemed to focus much of its attention on the positive. Tell us something about the darker side to Franklin that the exhibition doesn't touch on?

There are no “skeletons in the closet” that I am aware of.

“Benjamin Franklin-In Search of a Better World” at the Bowers Museum of Cultural Art, 2002 N. Main St., Santa Ana, (714) 567-3600; www.bowers.org. Open Tues.-Sun., 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Through March 13. $14-$18

Dave Barton has written for the OC Weekly for over twenty years, the last eight as their lead art critic. He has interviewed artists from punk rock photographer Edward Colver to monologist Mike Daisey, playwright Joe Penhall to culture jammer Ron English.