There are plenty of things about the documentary Colin Hay—Waiting for My Real Life that I was ready to dismiss off the bat. The rock & roll excess/redemption story, for one, is a genre that has been done to death. Hasn’t every great artist or musician had some sort of dance with the devil via bottle, powder or poison? It makes for great TV and movies—isn’t that the backbone of most VH1 Behind the Music episodes anyway?

There are plenty of things about the documentary Colin Hay—Waiting for My Real Life that I was ready to dismiss off the bat. The rock & roll excess/redemption story, for one, is a genre that has been done to death. Hasn’t every great artist or musician had some sort of dance with the devil via bottle, powder or poison? It makes for great TV and movies—isn’t that the backbone of most VH1 Behind the Music episodes anyway?

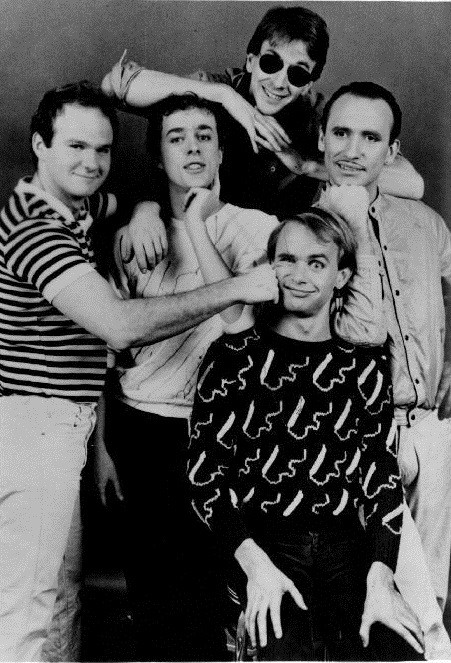

That battle with alcoholism is what brought the lively and spunky lead singer of ’80s group Men At Work, Colin Hay, to his knees after the group disbanded in 1986. That, along with the end of his first marriage and his solo projects failing to launch to the same height of success. You know how the story goes: Hay’s star took a detour down the road to ruin, finding its way back again to the success and admiration he deserves.

But what I was not prepared for was Colin Hay. Too often do I find myself sifting through channels on my car radio and changing the station whenever I hear Men At Work’s mega-popular “Who Can It Be Now?” (I know, I’m sorry, but I’ve heard it so many times). So I wasn’t aware that Hay actually has a solid following who love his solo work, his stage performances and just him. As Waiting for My Real Life portrays, Hay is a bare bones singer/songwriter who is actually authentic and personable and has been out of the public eye for the most part. He’s not looking for attention beyond a stage and/or a willing audience, if that. In the doc, Hay recounts a concert in the Midwest to which literally no one showed up, but he readied himself to perform anyway. “I guess it’s the Protestant in me,” he quips.

If you’re late to the Hay worship, too, the film lays out his entire life, including his family background and early beginnings in music. There’s even a dandy history lesson on Australia’s call for workers that abled his Scottish family to relocate there in the 1960s. Before that, he grew up in a music shop and was heavily introduced to all kinds of music.

First-time directors Aaron Faulls and Nate Gowtham follow the very rigid and rudimentary structure of the rock doc, which only frustrated me because the more live concert footage and intimate showcases with Hay I saw, the more I realized that Hay is not the average musician—he’s on a different plane of creative consciousness altogether, seamlessly blending his own brand of melancholy folk music, humor and candid storytelling in his performances. While it educated non-fans learning about him for the first time (like me), it would have been great if the directors had the technical and storytelling prowess to experiment more with the form to reflect Hay’s creative essence.

What you do see are a lot of talking-head interviews from former band mates, collaborators, friends, admirers, family, etc. I’m surprised a childhood friend didn’t sneak in to talk about Hay’s favorite schoolyard game or what snack they traded at lunchtime. When your film’s subject is alive and talking on camera, accompanied by intertitles for focal history points, at some point, the number of interviews becomes overwhelming—not to mention unnecessary. I can’t count the number of superfluous commentary such as “yeah, it’s hard” or “I met Colin at [insert place here]; he’s so great.” Edit these out and make room for more B-roll footage of Hay being awesome.

However, seeing this film at Newport Beach Film Festival Monday evening with a nearly sold-out crowd at Fashion Island’s Island Cinema, a viewer remarked how well it flowed together; I disagree, but it certainly picks up in the latter half, covering his post-Men At Work years. However, the directors fully accomplished getting me to care about this solitary musician, who laid out his soul in song for decades without much fanfare until now. I only wish his greatness wasn’t filtered through a standard documentary arc. Hay doesn’t need rando celebs such as Hugh Jackman, Wendy Malick or Guy Pierce, et. al, convincing you of his greatness; he can do that himself.

Stray observations:

• Much of Hay’s interviews are conducted in his kitchen, shot from a side angle as he stands up. I’m so glad a viewer asked about this in the Q&A session with Gowtham, who explained they intended a sequence in which Hay made coffee in the morning. The coffee didn’t happen, but Hay gave a great interview that lasted more than five hours; it’s just that seeing it onscreen is perplexing.

• Hay is so much bigger than Men At Work at this point that he deserves a film following him on his tour performances. Seriously, just point a camera at him doing anything, and I’m good.

• Singer Sia appears in this documentary, as she is a close family friend of Hay’s. Credit where credit is due, getting the elusive artist to make a full frontal appearance on camera is impressive.

• Say what you will about the movie, but I will always stand up for the Garden State soundtrack, which features Hay’s “I Just Don’t Think I’ll Get Over You.” Kudos to Zach Braff for his superb musical taste.

• The story of Hay playing a concert in his Scottish hometown is gold. He’s onstage, and the venue owners glower at him to make an announcement that there’s a car blocking the neighbor’s driveway. “Welcome home!” he says.

• I love how in the early days of Men At Work, Hay fully embraced his lazy eye, eventually naming one of his labels Lazy Eye Records.

• Mick Fleetwood’s living room is unsurprisingly glorious.

• I really need to check out Men At Work’s Cargo, and so should you.