Originally, I was going to devote this essay to trashing Hollywood for its ever-present Latino laziness. I was going to focus on the current fad of networks and streaming services approving anything and everything narco-related, rip apart clueless execs, and lead a storming of the Bronson Gate afterward—or something like that. After all, it has gotten out of control!

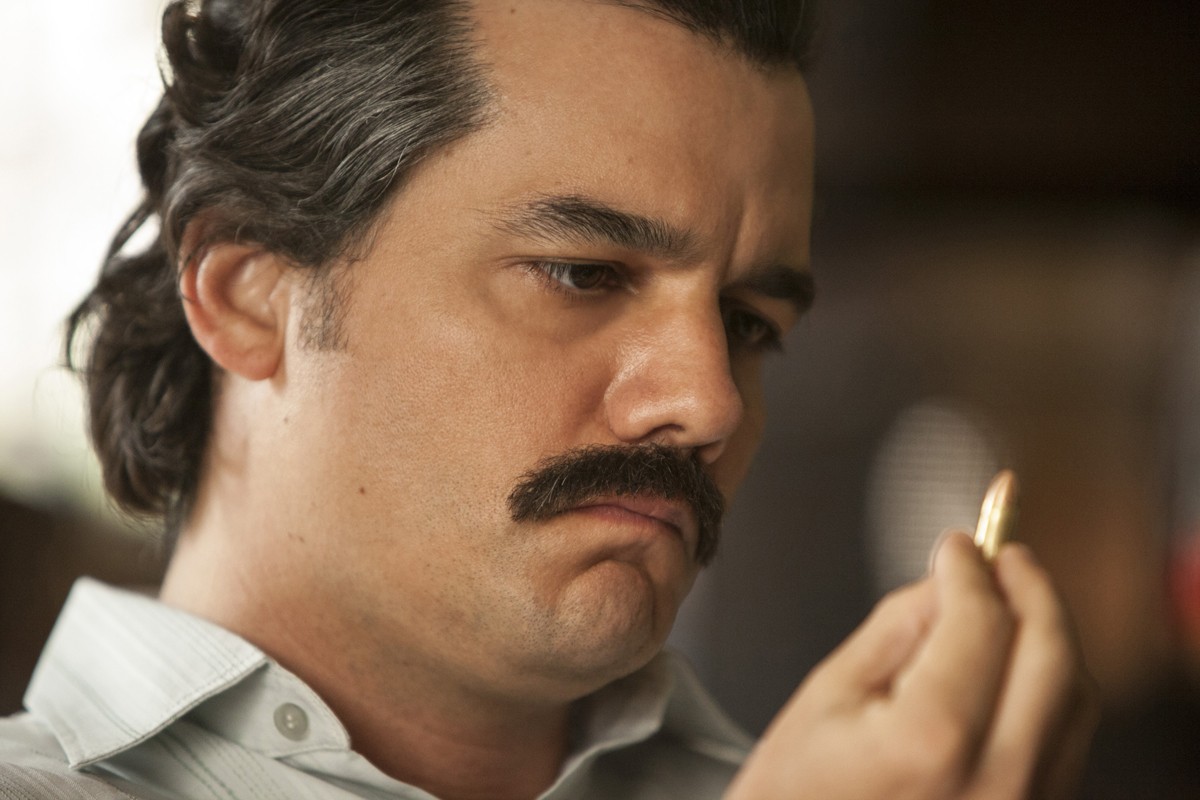

Netflix, for instance, just approved two extra seasons of Narcos, even though protagonist Pablo Escobar gets killed at the end of this season (oops, forgot to say: spoiler alert!). Amazon is doing a remake of Martin Scorsese's The Departed, updating the plot so that it happens in Chicago among Mexican-Americans. USA Network renewed Queen of the South, its adaptation of the Telemundo novela La Reina del Sur, itself a follow-up of sorts to the network's El Señor de los Cielos, based on the life of legendary Mexican drug lord Amado Carrillo Fuentes. And this, of course, follows years of television shows such as Breaking Bad and The Bridge, as well as coming attractions such as Univisión's dramatization of the life of El Chapo and Jennifer Lopez producing a limited series on infamous Colombian narco queen Griselda Blanco.

Too many narcos, not enough positive Mexis, ¿que no? But then cool pop-culture website Fusion beat me to my rant with an essay titled, “The Problem With Hollywood's Obsession Over Latino Drug Lords.” And as I read it, I had an epiphany. The piece predictably argued—as I was planning to—that such typecasting at the expense of other depictions is harmful to the popular image of Latinos and an indictment of Tinseltown's persistent lack of diversity. That's all true, but author Caitlin Cruz also missed a fundamental point that I finally realized: The narco will never disappear from the big and small screens, nor should it. See, Mexicans and Americans need him (or the occasional her): its eternal popularity is an unlikely Cassandra of the War On Drugs, exposing each side's sins, ones no one wants to admit.

As film archetypes go, the narco is a somewhat recent development with deep roots. It's a modern-day interpretation of the gangster, itself a take on the bandito, itself a distillation of the original dirty Mexican: the “greaser,” the intoxicated, violent, sneaky, half-breed villain of American letters that dates back to the Mexican-American War. Though cinema has depicted Mexicans as greasers from the start, the first drug smugglers in the Hollywood imagination were actually Chinese; indeed, the earliest known depiction of drug use on film is the Edison 1894 reeler Chinese Opium Den.

Hollywood wouldn't get around to depicting Mexican narcos until Borderline, a 1950 yarn starring Fred MacMurray and Don Bren's stepmom, Claire Trevor. The B-movie came at a crucial point in American-Mexican relations; the border, historically far away for most Americans, suddenly became a danger that threatened to spill into Anglo communities. Swarthy smugglers had generally received a free pass from studio depictions—perhaps because they had hooked up stars with things to smoke, drink and fuck ever since Douglas Fairbanks and friends were caravanning down to Tijuana during Prohibition? But almost as if to make up for lost time, the Mexican drug lord became a new avatar of evil in the 1950s and has been ever since (the Cheech and Chong films don't count because they relied on another Mexican stereotype: the buffoon). The choice allows Hollywood to offer American audiences an easy way out for their complicity in the War On Drugs: Instead of accepting responsibility for their consumption, they just blame the Mexicans (and later on, of course, Colombians and Cubans).

For Mexican audiences, on the other hand, the narco has always been received as a hero, a perverse Horatio Alger story who shoots his way to the top by channeling another Mexican stock character: the valiente, the rural Übermensch. Drug users and purveyors were reviled in pre-1970s Mexico—a famous stanza in “La Cucaracha” ridiculed the alleged marijuana use of President Victoriano Huerta, while the first narcocorrido, “El Contrabando del Paso,” is a 1920s-era smuggler son's lament to his mother for his criminal ways.

But by the 1970s, as the American government gave millions of dollars to Mexico to eradicate poppy and marijuana fields in the Pacific states of Sinaloa and Sonora and narco empires began to grow in response to increased American demand, the narco figure became the modern-day Villa and Zapata: perpetual thorns to Yankee intruders. Their lavish lifestyles became aspirational stories; an entire movie genre, the narcopelícula, rose to document the ultraviolence, along with the narcocorrido. In a country in which the traditional corridors of power were closed to only the elite, seeing drug lords gain riches through sheer will of personality—and at the expense of el Norte—proved irresistible to Mexicans at large.

So while Hollywood demonized narcos for the American audience, the over-the-top depictions of wealth and charisma were catnip to Mexican audiences. That's why you can go to swap meets across Southern California and see T-shirts featuring Michael Corleone, Walter White and Tony Montana alongside homages to Chapo, Chalino Sanchez and narcocultura gods. Mexican audiences want to see narcos succeed because that's the only way Hollywood allows Mexicans to win, even if only for a couple of hours or episodes.

None of what I write, of course, is to justify the continued aversion to non-criminal, non-slutty Latinos on film and television. But ultimately, the popularity of the narco genre is an indictment of all of us—after all, Hollywood doesn't make things that don't sell. Americans can't accept drug films that point the finger at them; Latinos love that narcos are wrapped in bravado or luxury, and they don't bother to think about the devastation left in their wake. With cartels continuing to occupy large swaths of Mexico, Americans overdosing on cheap heroin in record numbers, both governments offering no answers, and audiences on both sides of la frontera eating up those wily anti-heroes, we deserve the hell we binge-watch.